The Chinese Year of the Ram will kick off at the end of this month, but for now it looks as if 2015 will be the Year of the Central Banks.

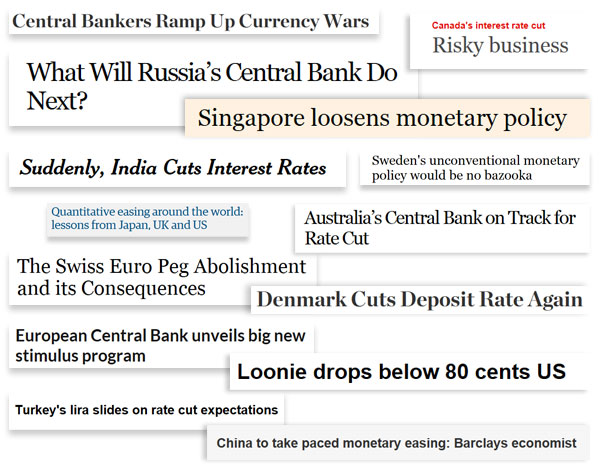

I spend a lot of time talking about gold, oil and emerging markets, and it’s important to recognize what drives these asset classes’ performance. Government and fiscal policy often have much to do with it. But in the past three months, we’ve seen central banks take center stage to engage in a new currency war: a race to the bottom of the exchange rate in an attempt to weaken their own currencies and undercut competitor nations.

Indeed, amid rock-bottom oil prices, deflation fears and slowing growth, policymakers from every corner of the globe are enacting some sort of monetary easing program. Last month alone, 14 countries cut rates and loosened borrowing standards, the most recent one being Russia.

A weak currency makes export prices more competitive and can help give inflation a boost, among other benefits. “The U.S. seems to be the only country right now that doesn’t mind having a strong currency,” says John Derrick, Director of Research here at U.S. Global Investors.

Since July, major currencies have fallen more than 15 percent against the greenback.

Two weeks ago, Switzerland’s central bank surprised markets by unpegging the Swiss franc from the euro in an attempt to protect its currency, known as a safe haven, against a sliding European bill. Its 10-Year bond yield then retreated into negative territory, meaning investors are essentially paying the government to lend it money.

This and other monetary shifts have huge effects on commodities, specifically gold. As I told Resource Investing News last week:

Gold is money. And whenever there’s negative real interest rates, gold in those currencies start to rise. Whenever interest rates are positive, and the government will pay you more than inflation, then gold falls in that country’s currency. Last year, only the U.S. dollar had positive real rates of return. All the other countries had negative real rates of return, so gold performed exceptionally well.

Other countries whose central banks have enacted monetary easing are Canada, India, Turkey, Denmark and Singapore, not to mention the European Central Bank (ECB), which recently unveiled a much-needed trillion-dollar stimulus package.

A recent BCA Research report forecasts that as a result of quantitative easing (QE), a weak euro and low oil prices, the eurozone should grow “by about 2 percentage points over the next two years, taking growth from the current level of 1 percent to around 3 percent. This is well above the range of any mainstream forecast.” The report continues: “[European] banks, in particular, are likely to outperform, as they will be the direct beneficiaries of rising credit demand, falling default rates and the ECB’s efforts to reflate asset prices.”

Speaking of oil, the current average price of a gallon of gas, according to AAA’s Daily Fuel Gauge Report, is $2.05. But in the UK, where I visited last week, it’s over $6. That’s actually down from $9 in June. You can see why Brits don’t drive trucks and SUVs.

But that’s the power of currencies. China’s economy surpassed our own late last year, based on purchasing-power parity (PPP).

Financial columnist Brett Arends puts into perspective just how huge this development really is:

“For the first time since Ulysses S. Grant was president, America is not the leading economic power on the planet.”

An easier way to comprehend PPP is by using The Economist’s Big Mac Index, a “lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their ‘correct’ level.” The index takes into account the price of McDonald’s signature sandwich in several countries and compares it to the price of one in the U.S. to determine whether those currencies are undervalued or overvalued. A Big Mac in China, for instance, costs $2.77, suggesting the yuan is undervalued by 42 percent. The same burger in Switzerland will set you back $7.54, making the franc overvalued by 57 percent.

Earning More in a Low Interest Rate World

From what we know, the Federal Reserve is the only central bank in the world that’s considering raising rates sometime this year, having ended its own QE program in October.

Last month we learned that the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or the cost of living, fell 0.4 percent in December, its biggest decline in over six years. We’re not alone, as the rest of the world is also bracing for deflation:

Following Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s announcement last Wednesday, the bond market rallied, pushing the U.S. 10-Year yield to a 20-month low.

Interest rates remain at historic lows, where they might very well stay this year. But when they do begin to rise—whenever that will be—shorter-term bond funds offer more protection than longer-term bond funds. That’s basic risk management. We always encourage investors to understand the DNA of volatility. For example:

Every asset class has its own unique characteristics. Do your due diligence.

Disclosure and Disclaimer: Please consider carefully a fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses. All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the link(s) above, you will be directed to a third-party website(s). U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by this/these website(s) and is not responsible for its/their content.