A recent article from Schwab included the text below—after some ETN bashing:

Why would anyone buy an ETN?

Given that ETNs carry credit risk, you might wonder why anyone uses them at all. But there are a few features that attract some investors to ETNs.

The ominous specter of credit risk does hover over ETNs. If the writer wants to play it even darker they can mention that ETN are unsecured notes. That can’t be good.

These prognostications remind me of the typical warnings regarding short selling—reminding investors that theoretically a short seller is exposed to infinite losses. They never mention that a lot more stocks have gone to zero than have gone to infinity.

In their six year history, which includes the 2008/2009 financial meltdown, a grand total of three ETNs have gone bust due to credit default—all 3 were issued by Lehmann Brothers. The total loss to investors was less than $15 million. How many public companies have gone bankrupt, rendering their stock worthless, in the last six years? A lot more than three, and a lot more than $15 million was lost—but I doubt we’ll ever see a Schwab article including the text below:

Why would anyone buy a stock?

ETNs are not suitable for everyone, but credit risk is not at the top of my check list of reasons not to own them. My list in priority order:

- You don’t understand the index the funds are intending to track. This includes the people complaining that volatility funds don’t accurately track the CBOE’s VIX index

- You don’t understand roll cost for futures based funds (e.g., volatility, commodities)

- You don’t understand the compounding errors of resetting inverse and leveraged funds

- You don’t monitor your fund— in particular to see if your fund has stopped creating new shares. A good way to do this is to setup a Google alert (e.g. TVIX ETN). You can configure the alert to send you an email periodically if there are any new web references to your alert text.

- You don’t know that some funds can be terminated due to large percentage moves or dropping below a given level

- Credit risk

Of these 6 items, only 4 and 5 are specific to ETNs, all the others, including credit risk can be problems for ETFs too. I’ll discuss credit risk for ETFs at the end of this post.

So what is this dreaded credit risk?

Unlike stock which offers ownership of a company, corporate bonds and notes are debt obligations. If a corporation gets into financial trouble to the point where it can no longer meet its obligations (e.g., interest payments, ETN share redemptions) then it goes into default and the holders of these notes and bonds may only get some portion, or sometimes none of their money back. The risk of a company defaulting is called credit risk. When a company defaults its stock has lower priority, or rights to company assets than either notes or bonds—typically the stock holders get nothing.

ETNs are usually unsecured senior notes, which means they aren’t backed by collateral, but by virtue of being senior they have higher priority than general corporate bonds.

If you want to know the credit risk of an ETN there are at least two things you can check:

- The credit rating of the issuing company

- The current price of the Credit Default Swap (CDS) on the issuing company. Below is a Bloomberg chart showing Barclay’s 5 year CDS in Euros over the last year.

Barclays 5 Yr CDS in euros

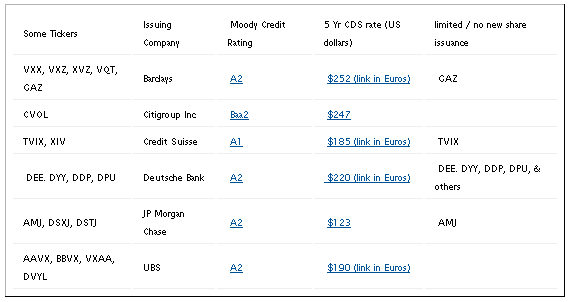

Credit ratings area available free online by companies like Moody’s and S&P, although you will need to register to get access. CDSs are essentially insurance policies on debt from a company (or country). If the market thinks the risk of an entity defaulting on its debt is increasing, then the price of the CDS goes up. CDS prices are available for free on services like Bloombergs. The chart below shows credit ratings and CDS rates for some of the companies that issue ETNs.

For reference, 5 Yr CDS for a couple countries:

- Germany $70

- Spain $533

- United States $56 (link in euros)

As I mentioned above, some ETFs have credit risk too—if they include swaps as part of their portfolio. I haven’t done a systematic search, but they are used by leveraged volatility ETFs (UVXY holdings) and commodity ETFs (UDC holdings). Swaps are notes issued by companies that offer performance tied to a specific benchmark (e.g., interest rates, volatility indexes, commodity indexes). If the issuing company goes bankrupt the note will likely be compromised. In the case of ETFs this credit risk is not carried by the issuer, instead any losses are passed directly to the share price of the ETF. ETFs try to manage this risk, for example with collateral, but the risk is there. See the UVXY prospectus if you would like to see more information about credit risk within an ETF.

Bottom line—the credit risk of your ETN is probably the least of your worries. By all means, bail out if the issuer gets in trouble, but the market itself is a far bigger risk to the value of your ETN.