With macro still very much mixed and resurgence risk a real possibility, we need to think about the prospect of the Fed finding itself in a “one-and-done“ situation on interest rate cuts.

This could result from any combination of global stimulus surprises (arguably already underway e.g. surge in rate cuts, China stimulus), a benign/business-friendly election outcome that removes uncertainty and sees pent-up expansion efforts by business stepped-up, ongoing resilient labor market, and services sector, higher for longer inflation, and/or a new commodities bull market.

It’s probably not the base case for most people, and from the Fed’s perspective — this is actually the risk they would prefer arguably they cut rates bigly as an expression of preference for the risk of resurgence vs recession.

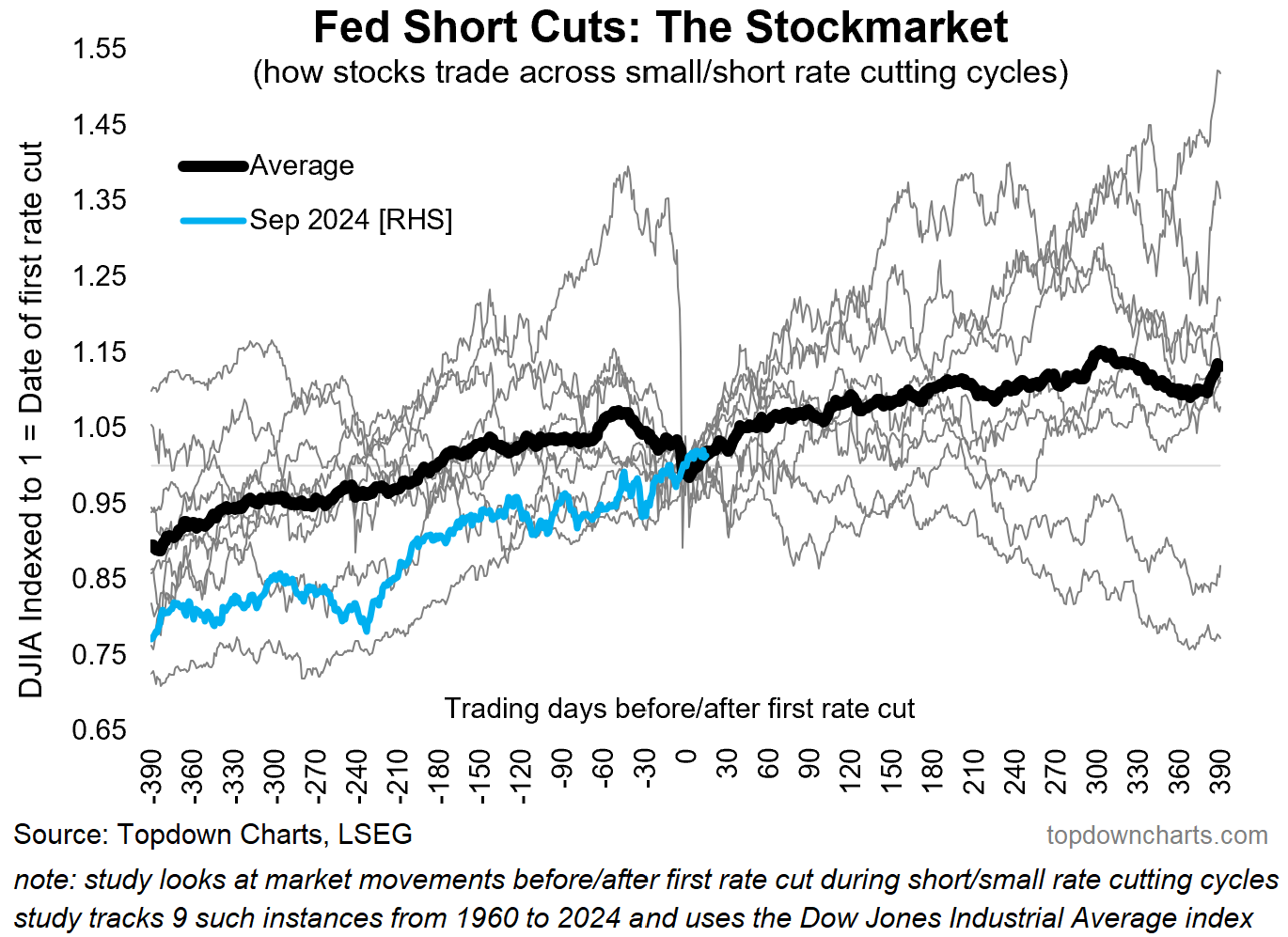

Being something that is both possible and plausible + somewhat non-consensus it’s worth looking at how markets traded through historical instances of short/sharp/small rate-cutting cycles (see chart below).

I identified situations where the Fed either brought interest rates down by a small amount or over a short cycle. Every instance followed at least one and often many rate hikes, and every instance concluded in a return to rate hikes. I identified 9 such instances over the 1955-2024 period.

Firstly, that tells us that it’s not entirely uncommon, and actually, about half of all rate-cutting cycles fall into this category. It’s partly a combination of the Fed getting it wrong and wrongly cutting rates, partly due to external developments and other things derailing the rate-cutting cycle, and of course partly due to the Fed just doing its job well and rate cuts actually helping and reviving growth/inflation.

But as to how the stock market tends to trade — it typically rallied over the 18-months prior, wobbled into the rate cut (often these cutting cycles were triggered by some event or scare), and then generally trended higher thereafter.

So a return to rate hikes or a situation of one-and-done might be a good thing.

Albeit I should point out there were some exceptions and a fairly wide range of paths. For instance, a sharp resurgence in inflation or even a short-lived recession could rattle stocks. Stocks which as a reminder are still pretty expensive (and n.b. the Fed has never before cut rates when stocks were this expensive).

Key point: Stocks tend to do well during small/short rate-cutting cycles.

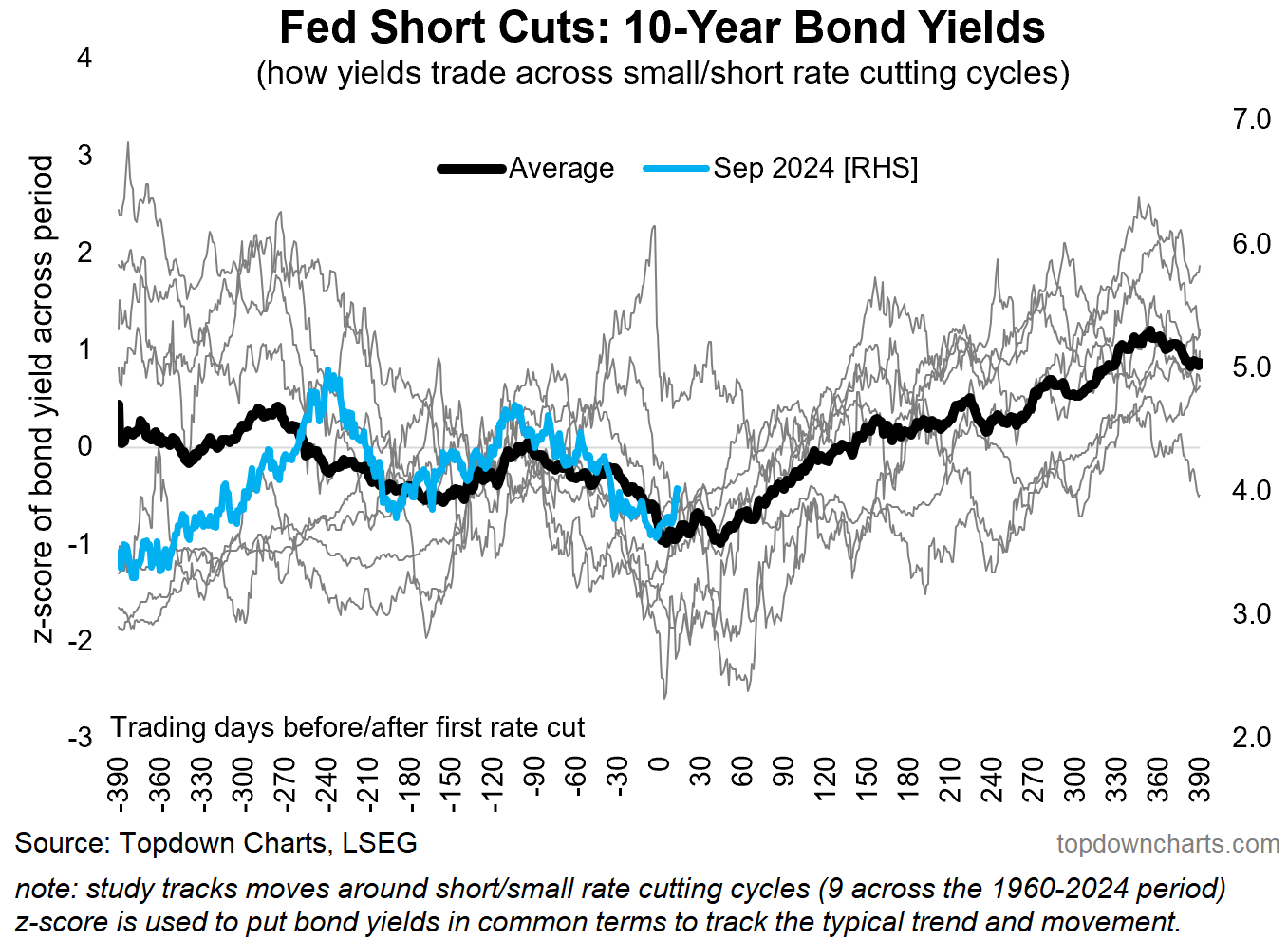

Bonus Chart: What About Bond Yields?

As you might guess, 10-year treasury yields tended to drift lower into the first rate cut, but in basically every instance bond yields pushed higher in the subsequent 18-months. This would have reflected the fact that short/sharp/small rate cutting cycles would most likely have been cut short by a resurgence in inflation or just generally better growth and market conditions.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.