Just days after the largest production cut in history, WTI fell below $20 per barrel.

The oil world was hyper-focused on what OPEC+ might do over the past week, and on what the Texas Railroad Commission might do as a follow-up measure. The cuts are massive. OPEC+ alone will cut by nearly 10 million barrels per day (mb/d). The market-induced contraction will make the output declines even larger.

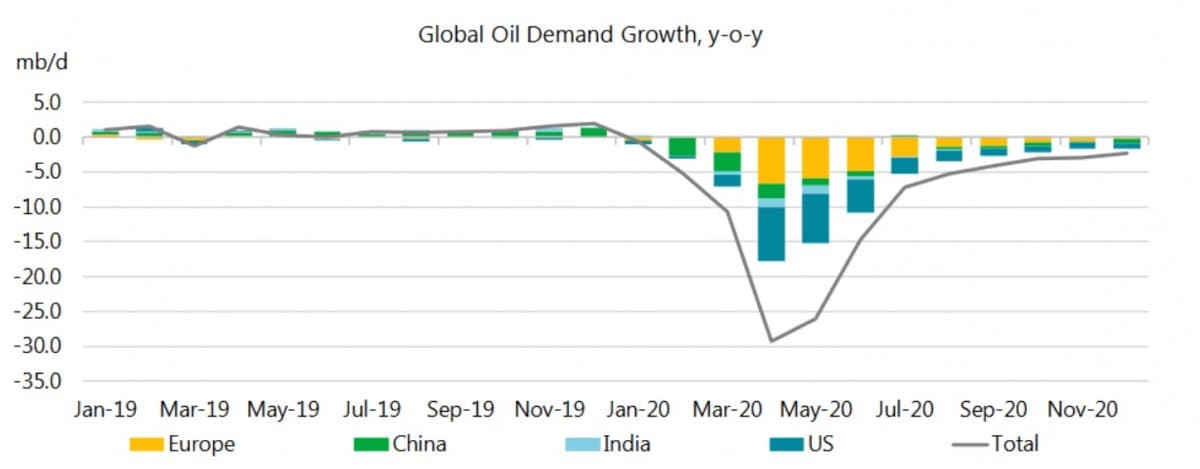

But the destruction in oil demand is both larger and much more immediate. April demand is expected to be down by 29 mb/d, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Oddly, so many forecasts from investment banks have predicted a V-shaped recovery for the global economy, but that scenario appears increasingly optimistic.

“The global economy is under pressure in ways not seen since the Great Depression in the 1930s; businesses are failing and unemployment is surging,” the IEA wrote in its April Oil Market Report, its first since lockdown measures went truly global. “Even assuming that travel restrictions are eased in the second half of the year, we expect that global oil demand in 2020 will fall by 9.3 million barrels a day (mb/d) versus 2019, erasing almost a decade of growth.”

The IEA assumes a version of a V-shaped recovery, although it says demand will be down for the rest of the year, including down 26-mb/d in May. For the full-year, the IEA sees demand contracting by 9.3 mb/d.

Against this backdrop, the OPEC+ deal is unable to engineer an immediate rebound in prices. “There is no feasible agreement that could cut supply by enough to offset such near-term demand losses,” the IEA said. However, the agency said the OPEC+ deal was a “solid start” that could reduce the buildup in inventories.

Because the OPEC+ deal falls far short of the decimation in demand, more supply cuts are coming, whether or not governments mandate them. With pipelines and storage tanks filling up, local prices are crashing. Western Canada Select has been trading in single digits since late March – WCS is currently below $5 per barrel.

WTI in Midland is as low as $10 per barrel, while West Texas Sour in Midland has plunged to $7 per barrel. These are prices that force immediate shut-ins.

The U.S. shale industry spent Monday arguing over whether or not the Texas Railroad Commission should regulate production. “Nobody wants to give us capital because we have all destroyed capital and created economic waste,” Scott Sheffield of Pioneer Natural Resources (NYSE:PXD) told the Texas Railroad Commission. “If the Texas Railroad Commission does not regulate long-term, we will disappear as an industry like the coal industry,” he said. That comment comes after years of shale executives boasting of low breakeven prices.

But the notion of regulation enraged other oil executives, some of which implied that producers may be trying to find a legal loophole out of their contracts. Diamondback Energy even threatened to cease all operations if Texas regulators imposed production cuts. “Diamondback will not be using any service providers to drill, complete or produce wells during the proration period,” Diamondback’s CFO Kaes Van’t Hof said, warning of “a sector with zero revenue and zero employment.”

It likely matters little what the Texas RRC does. Output declines are coming one way or another.

Global upstream investment is expected to contract by 32 percent this year, falling to $335 billion. The first to cut will be in the U.S. and Canada. “Heavily indebted independent US upstream companies had already signalled a 10% y-o-y cut in investments but it is now likely that spending will fall by 30%-40% to free up cash for service repayments,” the IEA said.

The agency said that roughly 2.2 mb/d of U.S. oil supply cannot even cover operating costs with WTI at $20 per barrel, including 1.2 mb/d of conventional supply. Another 1.3 mb/d of losses could come from the steep declines in existing shale production.