For much of the summer, financial markets seem to have discounted the possibility of action by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) in 2016. This was mostly due to a dismal May jobs report and the Brexit vote which increased uncertainty in financial markets. But market attention is now back on the Fed as confidence increases that the May jobs report was a hiccup in an otherwise strongly improving US labour market and that the Brexit shock is mostly confined to the UK. Markets have closely observed the Fed’s annual meeting in Jackson Hole over the weekend for clues about what the Fed might do for the rest of the year, starting with its next meeting on 21 September. Our view is that the Fed will raise interest rates once this year as the broad economic conditions are evolving in line with the Fed’s expectations set out in June.

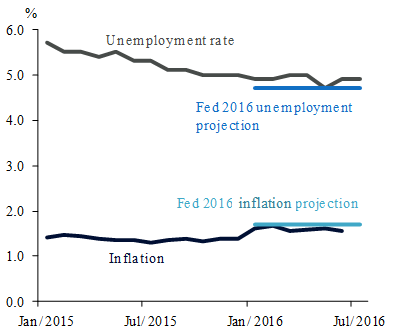

Core inflation was 1.6% in June, within a whisker of the Fed’s forecast of 1.7% by the end of 2016. Furthermore, wage growth has been accelerating in recent months, suggesting further gains could be on the cards. The unemployment rate was 4.9% in July, not far off the Fed’s forecast of 4.7% by year end. Jobs growth has improved at a remarkable pace, adding an average of 186k jobs per month, well above the 85k rate needed to sustain the unemployment rate. The labour force participation rate has also picked up after reaching a trough in September 2015. The improvement in inflation and the labour market has led the Fed’s vice-chairman, Stanley Fischer, to declare that “We are close to our targets.”

That said, the Fed has been quite dovish this year given its forecasts for inflation and unemployment and its historical behaviour. The Fed expects inflation to rise by 0.3 percentage points (pps) from 2015 to 2016 and unemployment to decline by 0.3pps over the same period. Historically, there have been 8 episodes in which inflation increased by 0.3pps and unemployment fell by 0.3pps. In 6 of these instances, the Fed raised rates three times or more over the course of the year. And the two times in which the Fed did not act were in 2010, in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis, when the US unemployment rate was around 9.5%, well above the Fed’s estimate of full employment.

Inflation and unemployment are on track to meet the Fed’s projections

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Fed, Haver Analytics and QNB Economics

Other indicators also lend support to Fed rate hikes this year. Activity is picking up. After a slow start in the first half of the year when the economy grew by only 1.0%, GDP growth is currently tracking 3.6% in the third quarter, according to the Atlanta Fed. The appreciation of the US dollar has eased in recent months, suggesting less of a drag on exports and growth in the future. Financial markets have stabilised after brief turmoil following the Brexit vote. The Fed members have started to talk up rate hikes again, including two recent and widely-covered speeches by the Fed’s vice-chairman and the San Francisco Fed’s president. As a result, financial markets are adjusting their expectations. They are currently pricing in 50% probability of at least one rate hike before the end of the year, compared to only 12% probability in early July.

In conclusion, economic conditions are ripe for another rate hike by the Fed this year. A rate hike in the September meeting is unlikely as markets are not yet prepared for it. Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) have shown that 90% of all US rate increases were at least 50% priced in 30 days in advance. This threshold has not been met as markets are currently pricing in 28% probability for rate hike in September. But while September might be too soon, the Fed will probably run out of excuses not to raise rates in December.