The news for the global coal industry has been painful of late. Coal prices have dramatically decreased nearly everywhere in the world amid considerable oversupply, inexpensive shale gas in the U.S., and various national-level environmental regulations. In recent years, China has been the boon for the coal world, but in 2014 the country’s consumption decreased 2.9 percent, although production notably still stood at a staggering 3.5 billion tonnes.

There are many reasons why China’s coal utilization has grown so rapidly to unprecedented levels, up 50 percent to 3.7 billion tonnes since 2005. Coal defines “energy security” in China, making up about 90 percent of the country’s fossil energy reserves. Another reason is China’s massive industrialization over the past few decades—this has also supported urbanization leading cities to grow at a rate of nearly 20 million people a year.

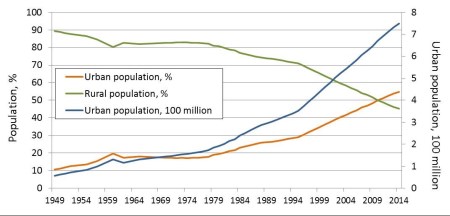

China’s total industrial production in 2007 was about 62 percent of that of the U.S., increasing to 126 percent by 2012. This trend provided an opportunity for many Chinese people to relocate to cities. They did so in droves to seek better employment and the proportion of Chinese urbanites grew from 20 percent of the population in 1980 to 53 percent today. Urbanization, industrialization, and coal consumption have been linked for the last few decades, but the government’s attempt to cap coal use by 2020 at an estimated 3.8–3.9 billion tonnes, coupled with a desire to increase the role of renewables and natural gas while also improving coal power plant efficiency, indicates that China is unlikely to provide much relief regarding the global coal oversupply glut.

Image Source: Cornerstone

While China may not be the answer to the coal industry’s current woes, the country’s recent history does shed light on a global trend that could buoy the global coal industry: urbanization. Coal is important for urbanization because it is the basis of production for three critical building blocks: electricity, steel, and cement.

Of course, coal is not the only option for electricity, but in much of the developing world, where urbanization can be a strategy to reduce poverty, coal is widely distributed, inexpensive, and its use is increasing. For example, in heavily coal-reliant India only 31.2 percent of the population lived in cities in 2011, but this is expected to increase to over 40 percent by 2030 and lead to nearly 600 million Indian urbanites.

India’s cities certainly face challenges, but access to basic services is far higher than in rural areas. According to the World Bank, in 2012 (most recent data available) less than 70 percent of rural Indians had access to electricity, while over 98 percent of those living in urban centers had access. To increase the living standards of rural Indians, Prime Minister Modi is looking to add electricity from every available source, including 100 GW of solar by 2022 and one billion tonnes of annual coal production by 2019.

Another emerging region with considerable access to coal is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As the 10 member countries band together, they hope their newfound unity can grow economies and improve the lives of their people. The United Nations is projecting continued urbanization in ASEAN with the percentage of people living in urban centers increasing from about 47 percent today to 67 percent in 2050. With the region holding 33 percent of the world’s coal reserves, coal production and consumption in ASEAN, especially for electricity, is climbing.

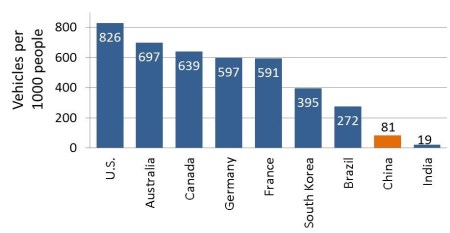

While India and ASEAN are just two examples of the potential for coal consumption to increase in the developing world, there is more to the story than electricity. Steel and cement production will also increase in the face of urbanization. In fact, the steel industry consumed about 1.2 billion tonnes of metallurgical coal in 2013. Projections for near-term global steel production increases are flat or even negative, but by 2018 steel production could be back to a more healthy growth rate, perhaps as high as 5 percent. This steel will be used for buildings, cars, etc. Just looking at the potential for an increase in vehicle production, consider that the number of vehicles per 1,000 people is about ten times higher in the U.S. than it is in China (826 versus 81) and India’s rate is less than one quarter that of China’s. Vehicle fleets expand with rising personal incomes. Around 55 percent of a passenger vehicle’s weight is from steel.

Coal is also the fuel of choice for cement production, resulting in 350–400 million tonnes of coal used to make cement today. The fastest growth in cement production of course is in the developing and urbanizing world, where abundant and inexpensive coal reigns as the fuel of choice. The growth in cement production is likely to be slower than what has been observed over the last decade, because reproduction of China’s growth rate is unlikely in the near-term. A middle of the road projection for annual global cement production in 2050 is 5.7 billion tonnes, which would require 475–540 million tonnes of coal calculated using current consumption rates.

There is certainly potential for urbanization to come to the aid of ailing coal markets and weak demand. But, this does not speak to the potential impact of COP21 (the climate change negotiations in Paris that will occur in December), national emissions reductions goals, China’s promise to cap coal by 2020, or the recent Papal encyclical. Proper planning and urbanization can allow for increased coal consumption while balancing environmental priorities, but the road must be paved today.

At their very core, urban centers offer some basic environmental benefits. For example, the unsustainable harvesting of biomass for cooking fuel and heating, largely occurring in rural areas, and leading to dangerous indoor air pollution, is much less prevalent in urban centers. Although energy use in cities is higher, grid-scale power plants can be built using fully commercial high-efficiency, low-emissions technologies, as recently highlighted by coal industry leaders. Urban centers also enable cogeneration, where heat from power plants is sent to industry or municipalities, one of the most efficient ways to use coal and other fuels. For deep de-carbonization, carbon capture and storage will be required in addition to energy efficiency, renewables expansion, more nuclear, etc.

While there are certainly challenges associated with widespread urbanization, they are vastly outnumbered by the opportunities. According to the United Nations, cities will be increasingly important in meeting the new Millennium Development Goals, due out in September, as almost all global population growth will occur in cities—nearly 1.1 billion new urbanites are expected by 2030. The growth of the world’s cities may provide the lever needed to lift global coal markets and global living standards as well. Although over 80 percent of the world lives in developing nations, it will be up to the already developed world to ensure that our own goals of protecting the natural world are met.