On March 9, 2016, front month trading for Japanese government bond (JGB) futures was halted at 12:32 pm Tokyo time. Selling had become intense, tripping the Osaka Exchange’s dynamic circuit breaker. The total length of the halt was just 30 seconds, but fingers were already being pointed in the direction of the BoJ.

More than four months later, on July 28, trading was halted in all products for JGB’s for an estimated 20 minutes starting 9:51 am Tokyo time. While the exchange provided very little information, they eventually blamed a delay in system processing. Whether or not that was the proximate cause doesn’t really matter, as the context for the trading darkness was just hours ahead of BoJ’s latest monetary policy decision.

A few days after that, on August 2, JGB 10s experienced their worst single day selloff in 13 years. That ended a 3-day selling binge that cut 2.47 points off the price of the 10-year benchmark, the largest three-day losing streak since May 2013 shortly after QQE had begun.

You might get the sense from these events that trading liquidity in JGB’s, cash or futures, isn’t exactly the most robust these days. Violent swings in bond markets are never a good thing in either direction (just ask the US Treasury). It’s not just government bonds, however, that have obtained a direct and palpable disdain from institutions that used to be a major part of the financial plumbing in Japan.

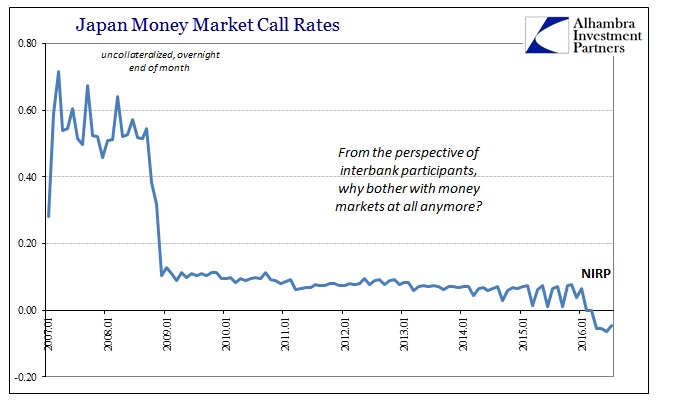

On March 8, just one day before the first JGB futures halt, every single one of the eleven Japanese asset managers that provided money market funds announced plans to close them to new investors and then repay their existing liabilities throughout the rest of this year. The money market business was over in Japan. In late February, fund sponsors had appealed to BoJ for a special exemption to overcome the sudden imposition of NIRP the month before but were rebuffed. There is far less in Japanese money market funds than in the US or Europe, so it wasn’t ever going to rise to the level of something like a systemic run but that isn’t Japan’s biggest risk in the wake of NIRP.

As money market funds shut down, so, too, did total interbank activity in the money markets. The Wall Street Journal reported in mid-April that:

Trading has withered in Japan’s money markets, where big banks and others usually park their excess cash hoping to receive some interest—despite predictions from the Bank of Japan that its latest easing of monetary policy would spark more activity. And there has been a rush in demand for Japanese government bonds even as many yields went below zero.

Somehow, despite this corruption in one of the central points of the modern wholesale financial system, the Journal manages to both call it the “latest easing of monetary policy” while also stating in the article’s introduction that this withering was an “unexpected” result of such “easing.” It’s an insult upon their readers’ intelligence to maintain orthodox shorthand in the very data and evidence that disproves both “easing” and “unexpected.”

The draining “rush in demand for Japanese government bonds” was entirely predictable, as I wrote a month before in mid-March:

Part of the answer can be found in NIRP itself, as even the BoJ’s three-tiered system only penalizes “idle” bank reserves and only so far. Rolling out of the equivalent of the Japanese deposit account and into a government bond escapes that monetary “tax.” The fact that such an effort is pushing up to 10 years in maturity demonstrates serious distortion (as of March 17, the 15-year JGB is safely positive at 15.7 bps but that yield, too, is pushing lower).

To roll into such long maturity negative yields, however, defies somewhat the point of holding even inert bank “reserves” in the first place. It adds elements of risk into the mix that go beyond trying to find the least costly monetary nothingness. That suggests something else working in concert to Japan’s banks.

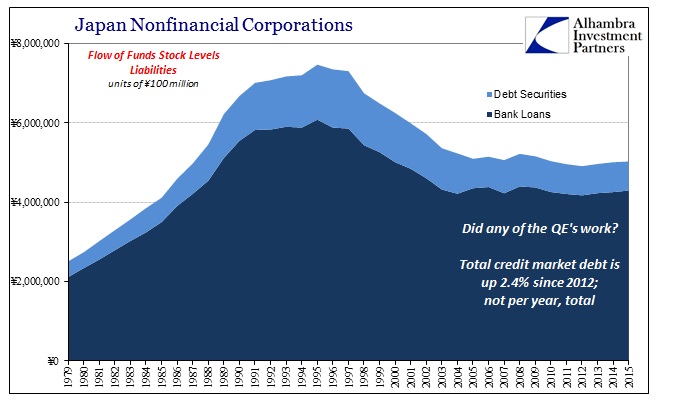

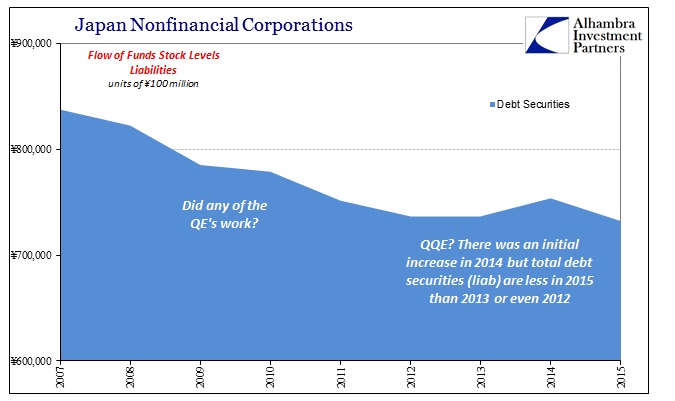

In fact, by that point yields on a great deal of the JGB curve were dropping or had dropped below the -10 bps threshold for the NIRP penalty. That is what negative rates intend, meaning they are axiomatically the opposite of “easing” as a matter of basic construction. The Bank of Japan in not finding success it expected out of QQE fully intended to penalize Japanese banks for holding all the reserves that it created as a byproduct of that policy (like the many QE’s before it). Until such time as BoJ and Abenomics decide to just circumvent banks entirely, Japanese institutions still reserve the right to refuse to participate.

Indeed, that is what they had been doing all along. The immense and swelled holding of bank reserves, as in the US, Europe, and everywhere else QE and its variants intrude, was itself a rejection of monetary policy at its core. In early April, as all these monetary developments achieved critical confluence, Takuji Okubo, chief economist at Japan Macro Advisors told CNBC that, “People are starting to feel the BOJ realized that lowering interest rates further doesn’t really help the economy and there’s significant international opposition to such a move.”

Among the “people” that have figured out the illusion of QE are these financial institutions. Because QE just doesn’t work where it is supposed to, there is no reward to providing the money dealing functions that the wholesale system requires. What banks and previous money market funds were left with was nothing but risk both in terms of economic conditions that never improve (and have gotten worse despite emphatic denials in the face of increasingly unambiguous evidence) but also monetary “easing” in the form of these increasing penalties. Why be in the business of money when there is no upside at all and a more harmful stance to monetary policy?

NIRP effectively answered that question and in the manner of common sense, which is why it was so unexpected to economists, policymakers, and writers at the Wall Street Journal. It is not just the usual monetary policy disruption, it is much more than that in terms of the risk calibration as I have described it and the Japanese have clearly shown it.

The implications of the disruption in money markets is far more than just JGB’s or even trading for yen. That was the indication noted above where JGB yields were often significantly below the NIRP penalty. As I described in March:

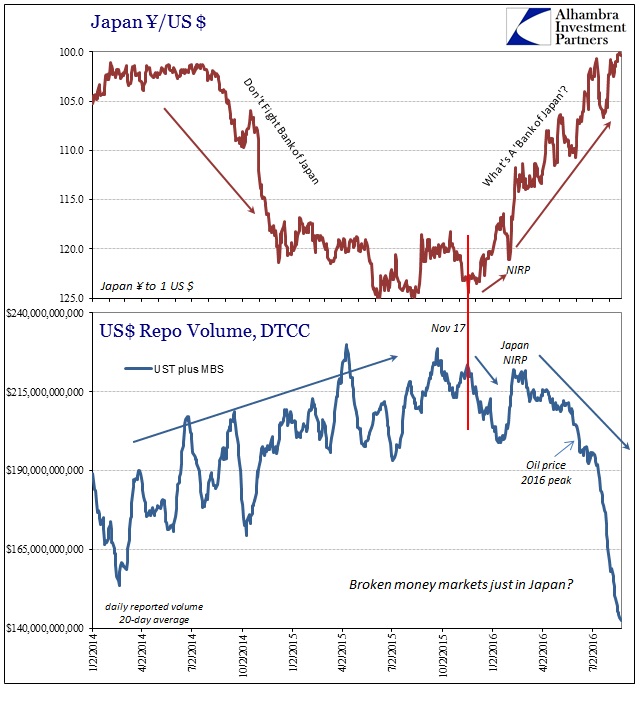

What’s most concerning about the yen avenue here in currency basis swaps is that they are on the “other” side of all this, also short the dollar as funding or borrowing costs skyrocket. If I am correct about Japanese banks being a major conduit for China’s “dollar short” then this will only enflame that retreat. Like negative swap spreads, the fact that these huge premiums are not being massively arb-ed by banks anywhere and everywhere only suggests internal-driven constraint. Though there has been a rush of speculation in yen, thus the JGB’s, the negative basis persists meaning any new lending in “dollars” doesn’t even replace whatever retreat from Japanese banks formerly providing them further down the eurodollar system.

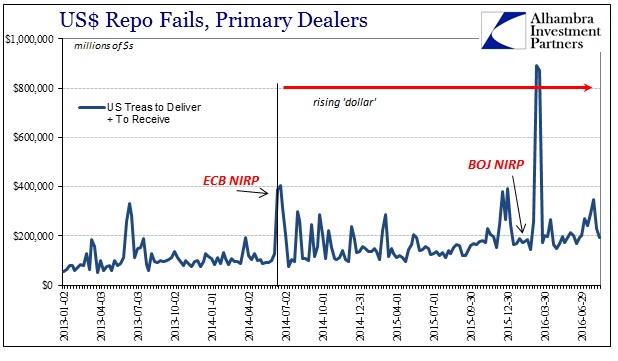

The diminishment of offered money market capacity due to NIRP in all its various forms has a global effect beyond internal yen conditions. Japanese banks have been a significant piece of the global wholesale system of credit-based reserve currency – primarily eurodollars. The forced incapacity that results from active BoJ penalization and the expectations of perhaps even more is a retrenchment of global money market offering including repo and FX (basis swaps). A local “tax” through monetary “easing” of NIRP is a global tax on all wholesale function.

In other words, what the Japanese and BoJ NIRP policy have done is to provide a clear example of the internal workings of the “rising dollar” itself and a big clue as to its origin. From this Asian perspective we can really appreciate why the “dollar” shifted in mid-June 2014. The European Central Bank had inaugurated its first “tax” on European wholesale bank functions on June 11, 2014, announced June 5. From nothing more than the Japanese money market experience of 2016 we can infer something similar of European banking dynamics, a segment of the global wholesale euro-dollar system larger than even Japanese proportions.

The idea of “easing” as a part of quantitative easing was already questionable not the least of which is due to the clear tightening bias in the real economy as interest rates sink and yield curves everywhere shrivel into the death of money. As part of NIRP, however, the notion about “easing” as an expected result of direct and intentional penalty upon voluntary (in)action is offensive. Central banks get away with this kind of clear destruction because they are never questioned, their assumptions always dutifully recited by a distinctly incurious media.

It is one of the greatest stories of our time, how the world’s central banks went “all in” on monetary “easing” and somehow the world finds itself short of both money and economy; as if money was actually destroyed rather than eased into it all. This is not just relevant to those places currently under NIRP, as monetary contraction is and has been universal. NIRP has been the most extreme form of amplification in that contraction, and thus the clearest example of what monetary policy is not.