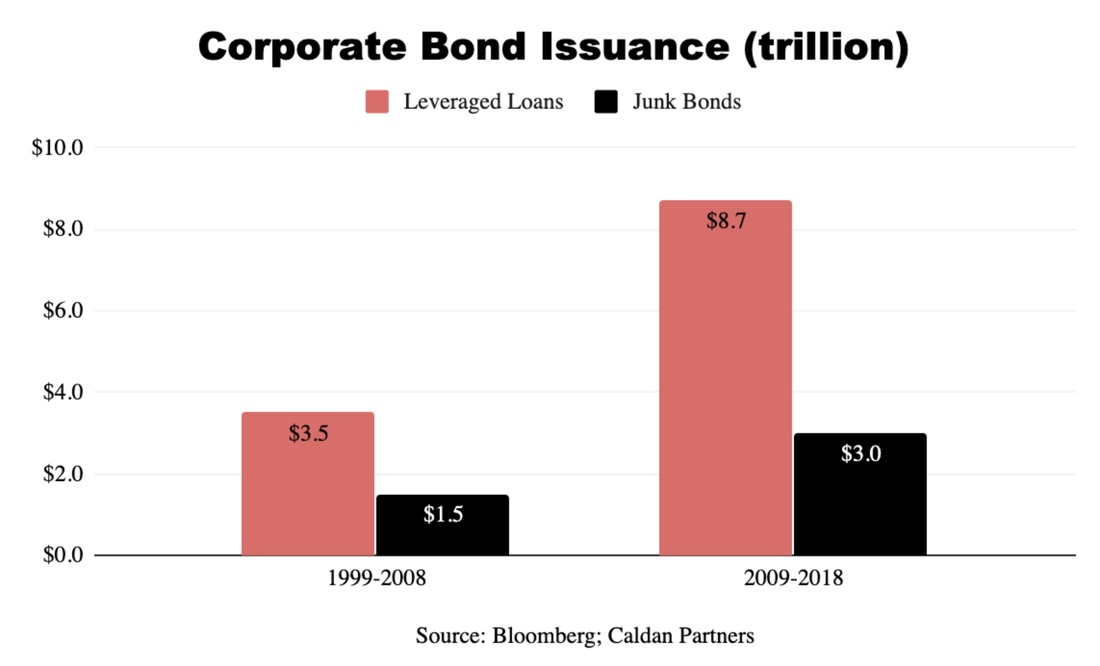

Caldan Partners: The surge in US corporate debt issuance has cast gloom over capitol hill as regulators are concerned that a prolonged period of low interest rates is masking underlying default risk. According to Bloomberg, US leveraged loan and junk bond issuance--which carries a higher risk of default--has nearly doubled in the past 10 years. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the use of leverage has shifted from households to companies, where more deals are done outside of regulatory view. We are concerned that intrinsic volatility in the riskiest corporate debt tranches (packaged together as collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs) could have a ripple effect on the real economy given the importance of leveraged loans as a source of corporate funding.

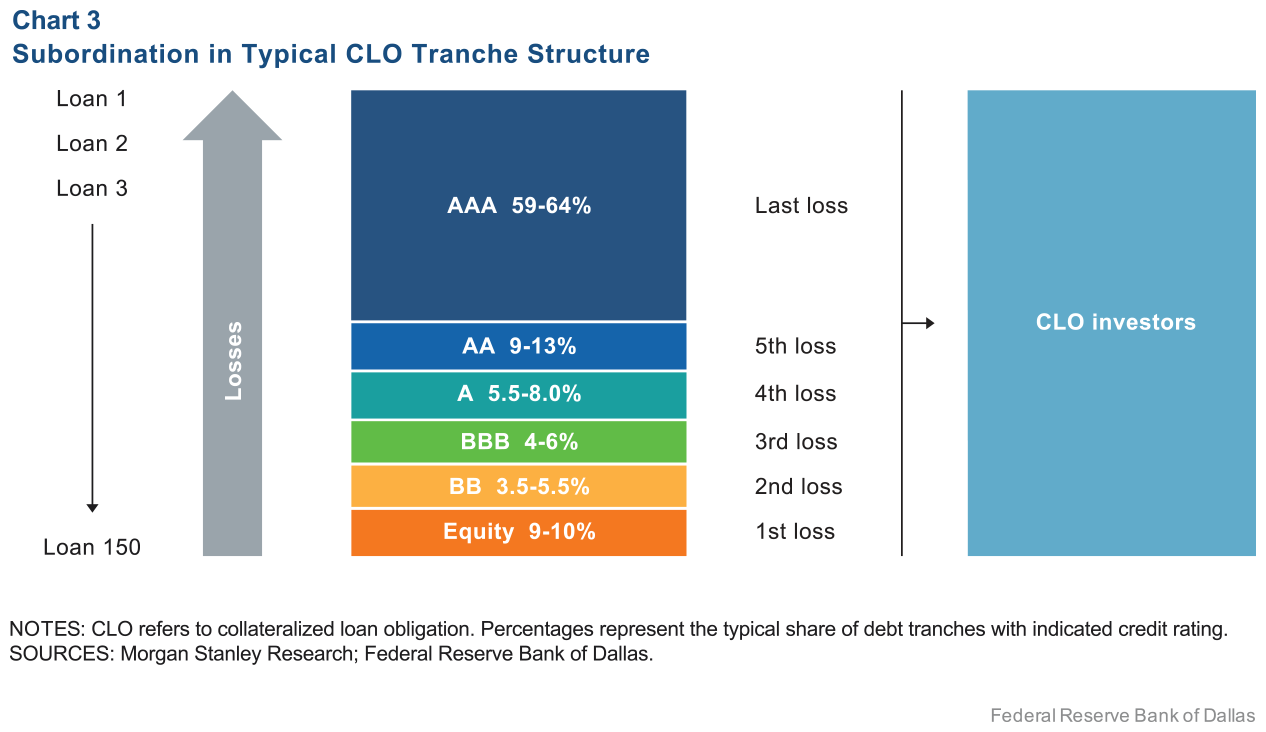

Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) are a portfolio of leveraged loans that are packaged together and managed as a fund. The CLO purchases a basket of senior bank loans that are made to companies, rated below investment grade, and then sold to investors. It's essentially a house of cards, whereby the highest rated loans receive a greater claim on the cash-flow produced by the underlying loan pool.

Regulatory Concerns

In February of 2018, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that CLO managers are no longer required to have "skin in the game," which means they are exempt from holding some of the risky corporate loans that were packaged up for sale to outside investors; and these loans are increasingly dealt outside of regulator view via non-banks. One such non-bank is Jefferies Financial Group, an independent brokerage firm with a 3% market share in leveraged loan underwriting versus 0.07% in 2007, according to Bloomberg.

Source: Dallas Fed article, "Corporate Debt as a Potential Amplifier in a Slowdown"

In September, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) held a hearing to discuss the potential impact that CLOs can have on the broader economy. One risk discussed by the SEC Committee was the increase in covenant-lite loans which reduce legal protections that would allow a lender to reassess or intervene before a borrower defaults. According to S&P calculations, cove-lite loans now make up about 80% of new issuance.

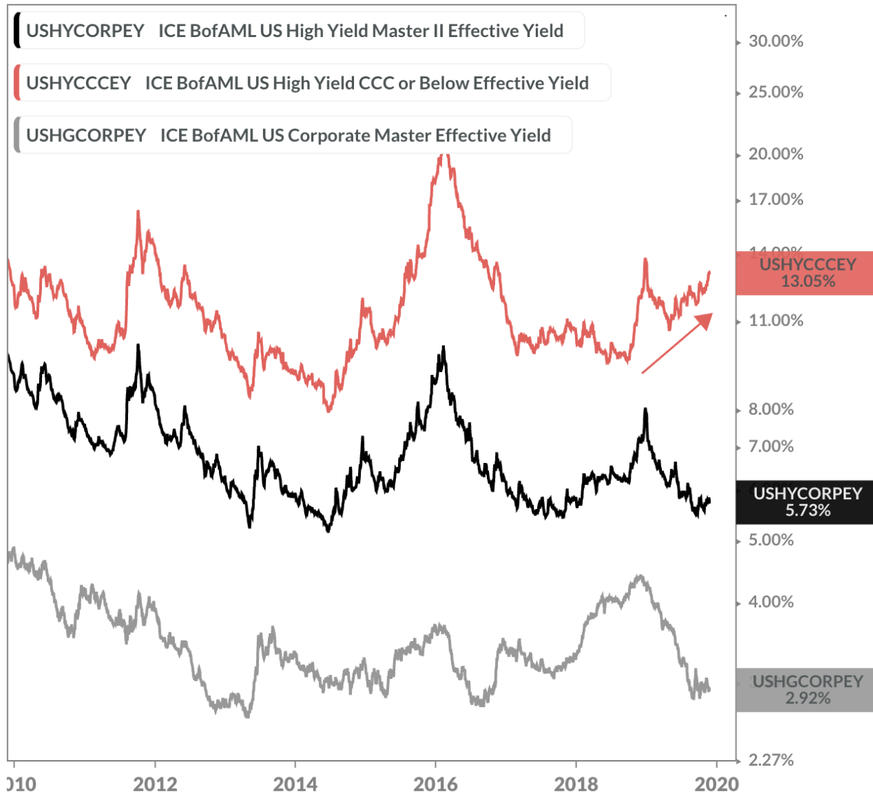

The Committee also expressed concern about low interest rates masking the quality of underlying loan risks. Adding to this problem is the disposition of CLO lenders shopping around agencies for better ratings, and even reverse-engineering rating methodologies to falsely align their junk risk to the higher quality investment-grade tranches. The Committee also highlighted inconsistent definitions of EBITDA (a measure of a company's net income, or earnings) across loan agreements, which adds another level of confusion when determining the true health of the underlying loan.

Market Implications

We are most concerned about demand drying up for CLOs, which can present a liquidity risk to financial markets. CLOs typically cap the amount of C-rated debt they can hold on their books to about 7.5% of total assets. Exceeding the 7.5% threshold can force CLO managers to take losses, which can trigger further selling of under-performing loans on their books.

The Wall Street Journal reported that junk-rated companies are sweetening deal terms by lowering loan pricing. This move, along with a higher distress ratio (the share of junk bonds yielding 10 percentage points or more above safer Treasuries) suggests that high-yield lenders are becoming more risk averse.

One measure of shifting risk appetite is the yield on the Palmer Square CLO Index, which remains elevated since its late 2017 low, meaning that investors are demanding greater compensation to accommodate for rising risk. The index measures mezzanine original rated A, BBB, and BB debt issued after January 1, 2011.

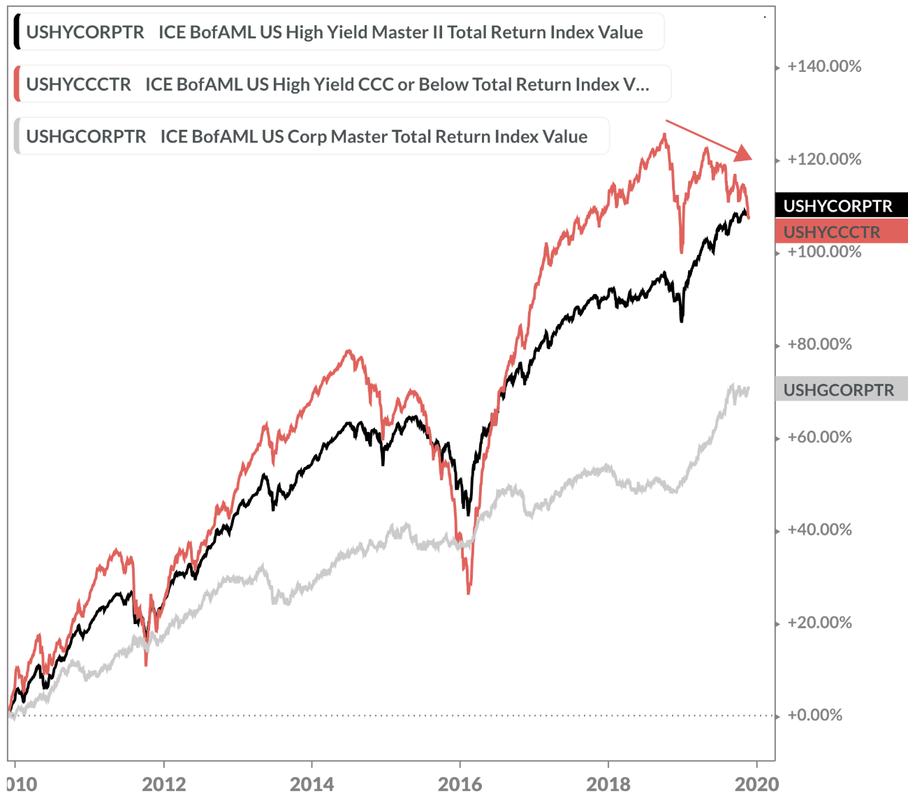

Lastly, the US high-yield CCC-rated total return index (left chart) has declined over the past year, while the overall high-yield and investment-grade total return indices continue to advance (yields, the inverse to bond prices, are shown on right chart), which could mean that the broader credit market is not priced for rising risk.