Chinese officials may not be enthusiasts of Hamlet or the “knavery” that transpired upon the Shakespearian stage, but their current desires to maintain investment capital inflows in the midst of quantitative easing is running into a roadblock due to its quasi-fixed foreign exchange rate. The general rule that economists have often cited is that, of this “trifecta” of monetary conditions, the best a country can hope for is to have two out of three, but never all three. The Chinese experiment of transitioning from a central planning model to something closer to western capitalism has had its ups and downs, but the health of the global economy is now bound at the hip with the Middle Kingdom.

So goes China, so goes future prosperity outside of its borders. While attention has recently focused on the Fed’s interest rate normalization exploits, falling commodity prices, and the European rollercoaster express, China is still attempting a soft landing after years of aggressive growth and subsequent years of declining demand from the West. As much as we would like to pretend that the goings on in China will not effect the rest of us, the truth is that decades of outsourcing and off-shoring of manufacturing resources and capabilities have inextricably tied our economic fates to those of China and its Asian copycats. We are well past the point of returning to the old days.

Is the China growth story real and what is this soft landing about?

The success story in China is real, and it has been phenomenal. Four decades ago, the nation’s annual GDP growth rate began to ascend into double digits, and in 1994, it finally peaked out at an astronomical figure of 35%. After a gradual descent, it regained momentum, only to peak again when the Great Recession came to town. From 2008, the story has been one of a glider, attempting its best to achieve a soft landing. Amidst rising doubts that current plans might backfire, Prime Minister Li Keqiang recently reassured financial markets that growth targets for 2016 were between 6.5% and 7%.

In case you missed it, GDP growth for 2015 came in at a level of about 7%. This and other government targets were presented at China’s annual parliamentary session of the National People’s Congress that kicked off during the first week of this month. One rating agency, Moody’s, had already downgraded sovereign bonds for China, based on its own internal outlook following the chaos in China’s stock market and the subsequent volatility experienced in foreign exchange markets. Chinese officials wanted to calm external critics and restore the public’s confidence that the current leadership can keep the economy moving forward.

Property and infrastructure investment growth was cut sharply in 2015, due primarily to excess capacity in the manufacturing sector and to excess inventory in Tier-3 and Tier-4 cities, where 70% of the investment had been. Stories that have been circulating about possible “bubbles” in the real estate market have more to do with the major cities in China, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. Growth rates in property investments will remain around 10% for 2016, but only after government intervention with infrastructure spending in railroads, highways, dams, irrigation waterways, and pipelines. Government deficits will rise to 3% of GDP. Foreign exchange reserves will be tapped, if necessary, and the money supply will be expanded to fill the gap.

The State is also committed to reforming what are called State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Many of these entities do not produce profits and are awash in debt, earning them the name of “zombie enterprises”. These companies are a drag on the Chinese economy, but their closure will generate bad loans for banks and bond defaults. A weaker national currency is expected to help exports, but the pressure on the Renminbi is increasing. With so many changes happening on so many fronts, there needs to be a self-regulating currency pressure valve, but the RMB is not freely float in today’s foreign exchange markets.

With prospects so rosy, why are analysts still overly concerned about China?

The situation in China is big, complex, and confusing. There are no precedents in history that can be compared to what has transpired over the past forty years. But, as one observer pondered, “The troubles in China are much larger than market participants believe. Everyone, including Chinese citizens, knows something is wrong, but few, if any, can put their finger on exactly what it is.”

Two symptoms have been abundantly clear, if only from the number of articles that have appeared in the press lately. Increasing capital outflows are ongoing, a sign that more currency devaluations are expected, and commodity prices have gone into a death spiral, much of which has been attributed to massive cutbacks in China due to diminishing demand, expanding inventories, and excess manufacturing capacity. These are only symptoms of a much bigger problem, but what is it?

After having lived through the last major global financial crisis, it is not difficult to focus suspicion on one and only one aspect of the Chinese economy – its banking system. When suspicion is backed up by a rating agency, then maybe we are on the right trail. In a recent report that seems to have remained in the shadows, Standard & Poor’s offered up an opinion that sounds eerily similar to conditions back in 2007: “We expect more negative ratings actions this year on Chinese banks. Deterioration in banks’ asset quality is likely to accelerate in 2016. Credit distress has been spreading from a few segments that private companies dominate – such as wholesale and retail trade, export-oriented light industry, shipbuilding, and coal mining—to broad-based manufacturing industries where large firms are common.”

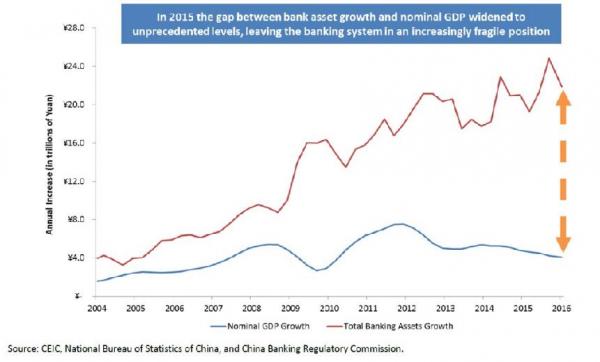

China’s growth success story required credit on an enormous scale. By one account, “This growth in investment was funded by rapid credit expansion in China’s banking system, which grew from $3 trillion in 2006 to $34 trillion in 2015. Today China is at a point where its banking system can no longer support such massive growth.” The following chart illustrates the fragility of the present situation:

As a result of the expanding gap on the right side of the chart, banking system assets in China, at least the ones that are not hidden off the balance sheet, are presently 340% of GDP. In 2007, similar figures for the U.S. banking system were 175% of GDP, in case you were curious. If China undergoes a typical non-performing loan cycle as it has in the past during previous run ups, then banking analysts foresee the need for $3.5 trillion in new banking capital from the Peoples Bank of China. A rapid expansion of the money supply will only put extreme pressure on the Rimenbi, forcing a significant devaluation.

Fasten your seatbelts – It could be a very bumpy ride!

The China success story is not confined to China. Its Asian trading partners have been on the ride of their lives, as well. The ravages of the Great Recession never reached Asian shores, and the concern now is that an after shock, like delayed karma, is headed in Asia’s direction. Capital outflows have been ongoing, an early sign that carry trades are being unwound or that funds are being generated to pay down U.S. Dollar denominated debt. Major commodity currencies, like the Aussie and the Kiwi, have depreciated accordingly.

When the financial crisis destroyed several large banks in the U.S., the Fed had to expand its balance sheet to the tune of $4.5 trillion to encourage investors to shore up existing banks with $650 billion in new equity capital. What will the PBoC have to do to raise roughly $3.5 billion? Can foreign exchange reserves provide some kind of buffer?

It was not that long ago that these reserves topped out at $4 trillion, but, following the recent downward adjustment of the Rinmenbi quasi-peg, the PBoC has had to intervene in financial markets to keep its currency value on track with policy targets. The result has been that forex reserves have been declining at about $100 billion a month. The current balance, according to published figures, stands at $3.2 trillion.

The problem with this reasoning is there needs to be a specified range maintained, in line with the breadth of the Chinese economy, to ensure working capital adequacy, a data point that the IMF routinely calculates for all nations. The IMF’s formula for its minimum level of forex reserves takes into account a nation’s exports, short-term forex debt, M2 money supply, and a catchall of other liabilities. When you work your way through the equation for China, the minimum forex reserve figure comes out to be $2.7 trillion. China’s immense economy requires this level of capital just to operate. Size matters, but just like any small business, basic working capital is a necessity.

Of course, this calculation effort is purely speculation, based on data supplied by the PBoC and other Chinese agencies, which have tended in the past to be understated or overstated whenever it suited political expediencies. In other words, the problems with China’s banking system could be woefully worse than is currently believed. If banking credit tightens and unemployment spikes, Chinese authorities may have to act more like their western banking brethren, deploying massive stimulus and expanding the money supply to jolt its economy back into competitiveness. The Rinmenbi will have to devalue, and once again, we will hear the screams of “Currency Wars” across the planet.

Concluding Remarks

At the end of the day, China will do what it has to do to save its banking system, perhaps by following the same script that every other central bank has followed in a similar position. But China is not Las Vegas. What happens in China will not stay in China. If there is a major banking crisis there, then its impacts will ripple through every market on the planet, especially the foreign exchange market. Carry trade positions will unwind, and cross-border capital flows will go through the roof. Analysts that have studied this possibility believe that the Rinmenbi could devalue as much as 30% versus the USD.

Although trading in Rinmenbi pairings will occur outside of traditional retail forex trading, a major devaluation will drastically reduce China’s purchasing power, making the death spiral in commodity prices look like a minor bump in the road. China, as large as it is, is still an emerging market, an experiment of sorts. Mistakes will be made, but, hopefully, Chinese officials will get a few things right along the way and avoid what many perceive as an imminent threat. In any event, caution is advised.

Risk Statement: Trading Foreign Exchange on margin carries a high level of risk and may not be suitable for all investors. The possibility exists that you could lose more than your initial deposit. The high degree of leverage can work against you as well as for you.