China’s economy has officially fallen into deflation – for the first time in two years.

The consumer price index (CPI) dipped -0.30% year-over-year in July. The producer inflation index (PPI) remained deeply negative at -4.40%.

All the hype surrounding China’s “inflationary” reopening – which happened more than 8 months ago – has fizzled out as many pundits begin to realize the structural imbalances in the world’s second-largest economy as it drifts into deflation.

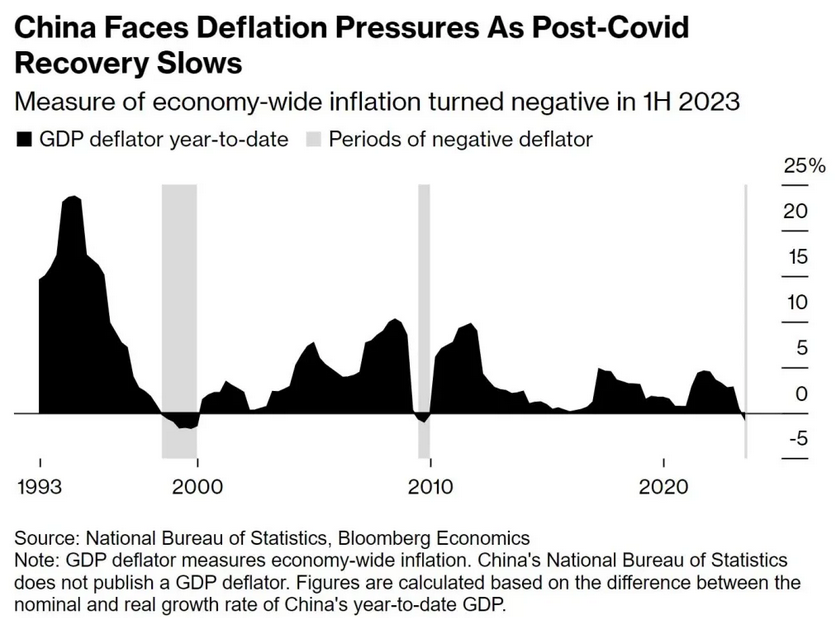

In fact, using the gross domestic product (GDP) deflator – a measure of economy-wide prices – China already entered deflation some time ago.

But I’m not surprised.

I wrote about China’s dependence on real estate back in November 2022. And how falling property prices would wreck balance sheets.

“.. . But most troubling is data showing 70% of total household wealth in China is in the property sector (compared to just 35% in the U.S.).

I believe this is the biggest issue since – in such conditions historically – ‘debt-deflation’ can compound very quickly. . .”

As prices of assets fall, Chinese households are shying away from new loans. And instead, they’re saving more money and paying down debt faster.

According to Citigroup’s chief China economist – Chinese households repaid some 4.7 trillion yuan ($700 billion) worth of mortgages early over last year.

This creates a reinforcing feedback loop:

- Less credit extended means less excess demand. Pushing prices lower. Which further pushes asset prices lower. Leading to a decline in the money supply (debt repayments suck money out of the economy). Thus amplifying the deflation, and on and on.

This is known as a balance sheet recession (read more here about it).

But to give you some brief context, a balance sheet recession is when balance sheets are burdened with high levels of debt, often resulting from a speculative bubble in real estate or other assets that burst, and consumers shy away from credit.

And this results in reduced consumption, decreased business investment, and a lack of overall demand in the economy. As a consequence, economic growth becomes sluggish or negative, and unemployment may rise.

Sound familiar?

Chinese leaders are dealing with an anemic consumer, diminishing returns on infrastructure investments, local governments in a payment crisis, and a fragile banking sector.

And it’s a toxic combination.

So, let’s take a closer look at all this. . .

Chinese Companies Feeling The Deflationary Bite

It’s clear at this point China is suffering from weak domestic demand.

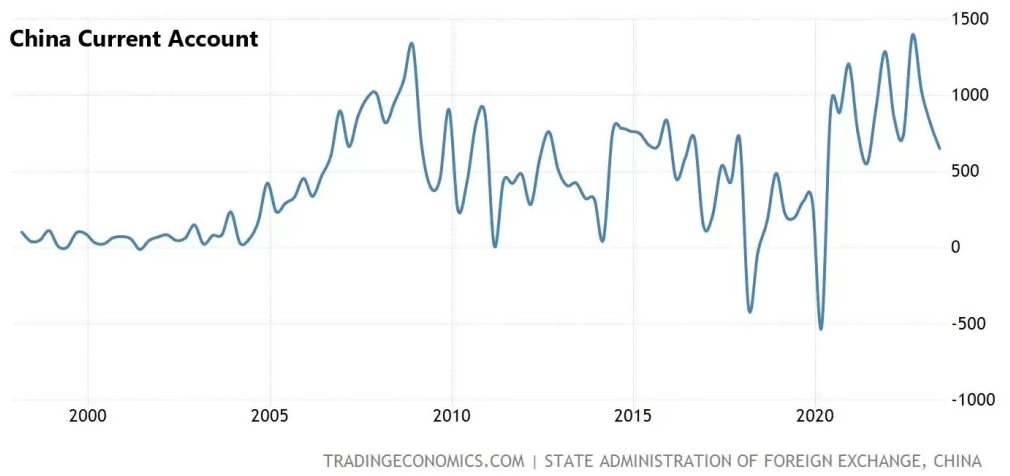

A good measure indicating this is China’s chronic current account surpluses.

China’s large current account essentially means they have more exports than imports.

Or – putting it another way – China’s demand is so weak that imports are falling faster relative to exports. Indicating they’re not consuming imports nor what they make domestically. And thus exporting the rest abroad.

Historically, China depended on growth by exporting its excess goods abroad.

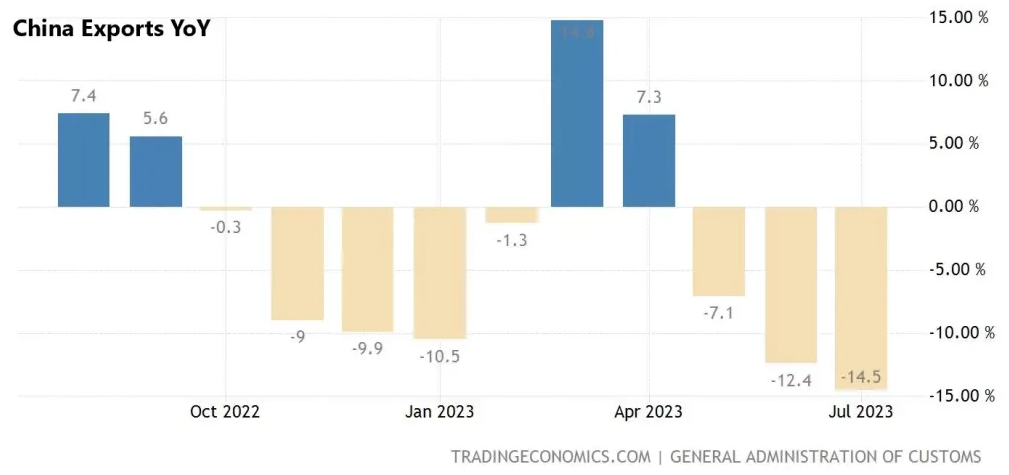

But now – as global demand erodes – China’s exports are sinking also.

For instance, China’s exports plunged -14.5% in July compared with a year earlier. And this trend has only amplified since May.

Also keep in mind that when China runs larger surpluses, it’s a net drain on global growth (and vice versa when it runs deficits).

Meaning that due to the less demand in China’s markets, they are instead exporting that deflation abroad.

This puts China in a sticky situation. Because if they aren’t consuming what they make domestically, nor can they depend on global growth to export it, then they must deal with deflation and unemployment.

For perspective, China’s youth unemployment is already at a record high of 21%. Some estimates believe it’s more than double this if you factor in those available for work (a staggering 46.5%)

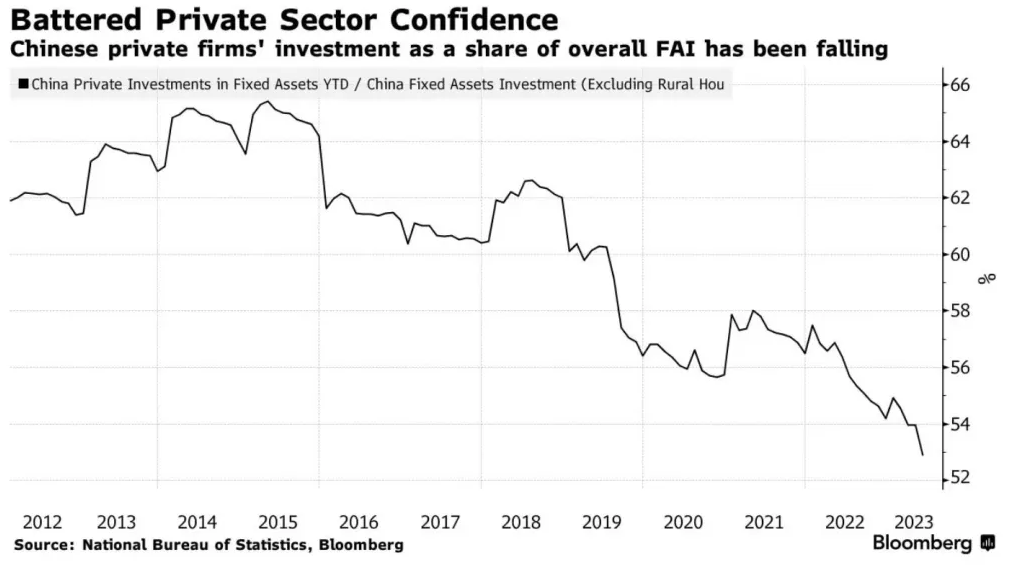

Thus, because of this weak demand at home and abroad – Chinese private firms (those not subsidized by the state) have not been investing.

According to Bloomberg – China’s private investment in fixed assets (FAI) has continued to plunge to decade lows.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise: why would a company invest in expansion when demand is anemic, and profits erode?

Annual profits at China’s industrial firms fell -16.8% in the first six months of 2023. And this follows the -18.8% plunge in the prior period.

Domestic Chinese companies are slashing prices to move inventory (amplifying the deflation), creating a competitive price war. And this is a vicious cycle that’s cutting into revenues and prompting firms to curb further investment and hiring.

As long as Chinese firms aren’t profitable and shy away from investing, I expect this will further hinder growth.

China’s Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) Are Beginning To Miss Bond Payments As Returns Plunge

There’s a ticking time bomb in China’s local governments.

These local governments are fundamental to China’s economy.

See, Beijing will set ambitious growth targets and these local governments will do whatever they can to hit them.

And these municipalities will issue debt through ‘local government finance vehicles (LGFVs) to fund their projects.

Now, it worked for years as infrastructure returns and real estate prices rose.

But not anymore.

After years of over-investment, diminishing returns, and sinking land sales – the debt-laden local governments have become a major risk.

LGFV debt reached 92 trillion yuan ($12.8 trillion) – or 76% of GDP – in 2022. Meanwhile, Beijing has warned of “hidden debt risks” as the numbers are even higher when accounting for any debt issued outside their balance sheets (essentially shadow banking).

It’s become an unsustainable situation.

As of last month (July 2023), a total of 48 LGFVs are overdue on commercial paper (debt that carries a maturity of less than a year). Up from 29 in June.

And while none have defaulted on a public bond (yet), there’s growing concern that LGFV repayment risk is nearing a tipping point.

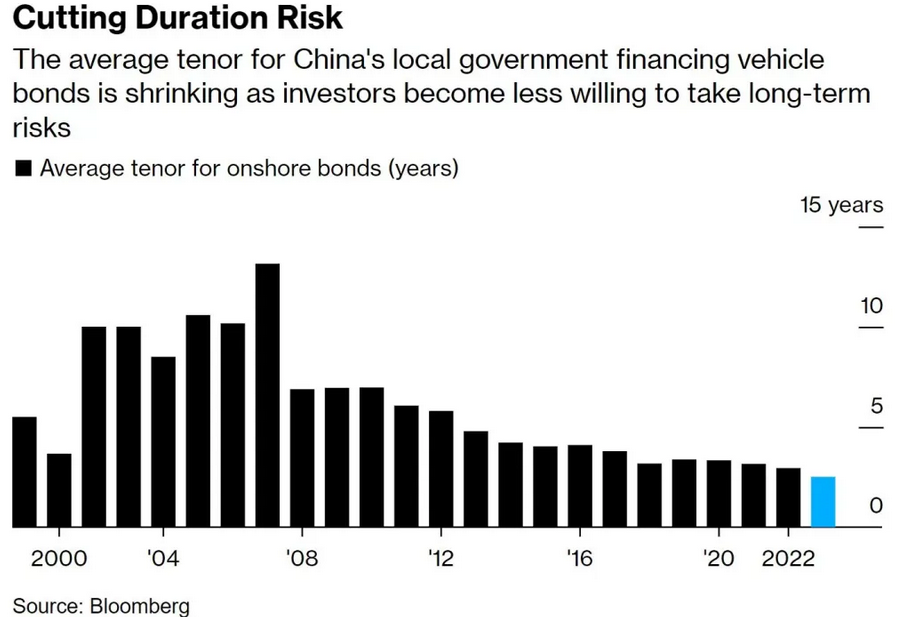

China’s state pension fund recently pushed for asset managers handling the funds to shed some LGFV debt and lower the durations of loans because of potential insolvency or illiquidity crises.

And this has put Beijing between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, if they provide aid to the LGFVs, it may spur moral hazard, reinforcing risky borrowing and poor investments.

On the other hand, if they don’t provide any aid, the Chinese growth model would collapse, spurring social instability and weakness in the Chinese economy.

It appears that – for now – LGFVs will simply try and roll over maturing debt at lower rates – aka ‘extend-and-pretend.”

Have no doubt, this is a structural issue with no easy way out. And how Beijing tries to tackle this will be pivotal in the coming quarters.

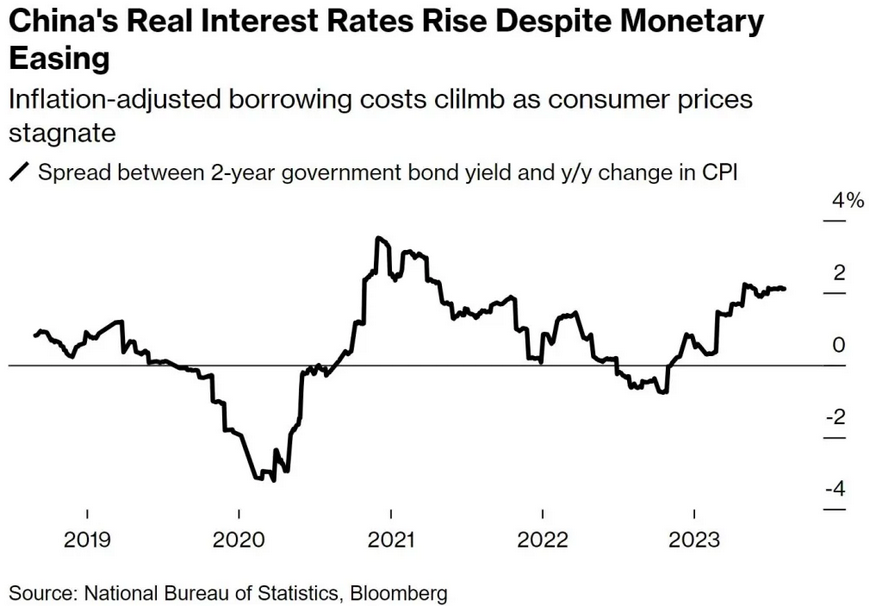

Deflation Is Making China’s ‘Real’ Interest Rates Rise – Strangling Growth

A big issue now plaguing China is that the deflation is driving up ‘real’ (inflation-adjusted) interest rates.

Thus pushing up debt servicing costs and making financial conditions tighter.

This puts pressure on the Peoples Bank of China (PBOC). Because if they try to cut rates further, it pushes nominal interest rates down (lowering the real rate in theory).

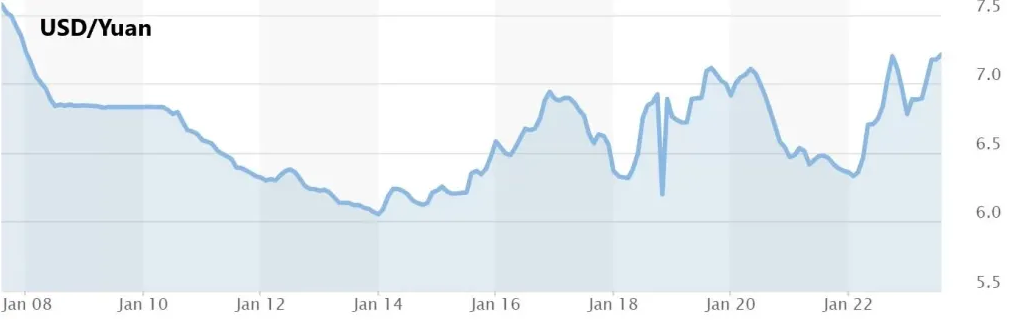

But it will also put pressure on the Chinese yuan – which has already dropped –6% to the U.S. dollar year-to-date.

Keep in mind that a weaker yuan is a form of tax on Chinese households (increases their import costs).

And this is already the problem in China – anemic consumption.

A weaker yuan will only amplify this.

Another issue with cutting interest is that Chinese households may save more to make up for the less interest income.

China’s gross savings rate as a percentage of GDP is a staggering 45% (as of 2022).

As Chinese consumers spend less, repay debt faster, and inch towards the demographic cliff – they’re saving more. Not less.

And this is clearly becoming a drag on growth.

In Conclusion

China’s economy is facing some serious challenges right now.

The whole inflation hype that was going on a while back has fizzled out. And the country has actually slipped into deflation.

This will have negative impacts if it persists (which I expect it will) – especially for commodity prices and global growth.

This is important because it means prices are dropping, and that can mess things up in a bunch of ways – from property problems to struggling companies and shaky over-indebted local governments.

How Beijing handles these challenges will really shape what happens next.

The authorities have already promised a wave of stimulus and focused programs to try and kickstart the economy.

But it’s mostly been talk, and no actual plan.

It appears China’s unbalanced economy has finally caught up to it.