China Bears have been licking their chops over a recent slew of negative economic data and headlines coming out of the Middle Kingdom. Things are getting real. Really real.

I wanted to highlight three noteworthy tidbits on the topic:

1. Where will a China slowdown hurt most?

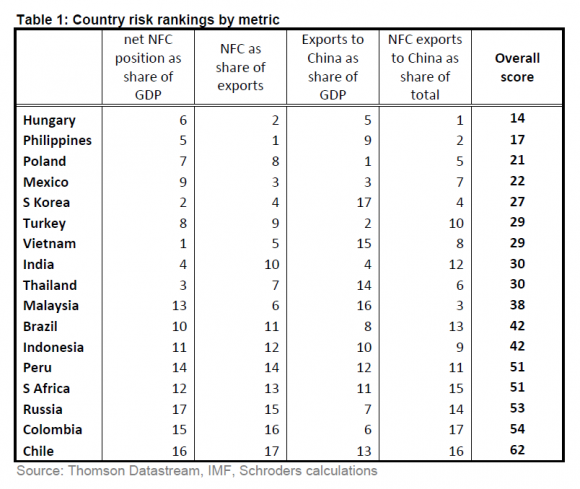

A table from Thomson/IMF via @reformedbroker outlines the countries most at risk if China’s economy contracts. Not surprisingly, commodity-based emerging markets (Chile, Colombia, Russia, South Africa) have the greatest exposure.

2. How are Chinese authorities addressing the issue?

With so many overlapping interests, it is impossible terribly difficult to forecast the People Bank of China’s (PBOC) policy response to the current situation. The Australia-based economic blog Macrobusiness has a decent roundup of the government’s attempt to manage the slowdown.

- From Business Spectator:

“Premier Li said the goal of 7.5 per cent was flexible and the government could tolerate both higher and lower growth rates. However, he said the floor growth rate that was acceptable to Beijing must guarantee sufficient employment as well as income increases.” - From Societe Generale

“This is a very fast deceleration…This is really beyond the tolerance of the Chinese government. As a result, I think they will cut the required reserve ratio quite soon or do some easing.” - From Bank of America ML

“the Chinese government has already taken some action, evidenced by significantly lower interbank rates and cheaper CNY. After the Lunar New Year (LNY) holiday, we expect Beijing to ramp up spending on infrastructure and social welfare projects including starting 7.0mn units of social housing.”

3. What the heck is going on?

I often wake up in the middle of the night wishing I had the 10% of the mental chops of Michael Pettis (and since we only use 10% of our brains, I basically only want 1% of Mr. Pettis’); this man knows China cold. His blog and books are a tremendous resource for understanding how the Chinese economy will play out.

Earlier this month, Mr. Pettis penned an essay titled “Will Emerging Markets Come Back?”. The article touches on many issues but his take on “decoupling” – whereby developing markets are no long dependent on developed markets for economic growth – is particularly interesting. Since 2008, many observers believed this decoupling would spare developing markets from the debt-fueled sins of North America and Europe. The emerging middle-classes of India and China were to drive growth for the global economy; in reality, it was a debt-driven investment binge by China that has buoyed the global economy. It was never sustainable and we are really beginning to see the model crack.

- “In China well before the crisis we were already experiencing the problem of excess investment in manufacturing capacity, real estate and infrastructure. In developing countries like Brazil this was matched by investment in hard-commodity production based on unrealistic growth assumptions in China. Weaker demand in the rich countries, especially weaker consumption, should have reduced whatever the optimal amount of global investment might have been, especially as we already suffered from excess capacity. To put it schematically:

- Before the crisis the world had already over-invested in real estate and manufacturing capacity based on unrealistic expectations of consumption growth.

- The global crisis forced consumption growth to drop. This should have meant that if investment levels were too high before the crisis, they were even more so after the crisis.

- Instead of cutting back on investment, however, the developing world reacted to the drop in rich-country demand by significantly increasing investment, driven at least in part by worries that the consumption adjustment in Europe and the US would cause a collapse in export growth which would itself force unemployment up to dangerous levels.

Clearly this wasn’t sustainable, and not surprisingly soaring debt is now forcing this investment surge to end. As a result, we are now going to experience the full impact of slower consumption growth in the rich countries, but instead of this being mitigated by higher investment growth in the developing countries, it will now be reinforced by slower investment growth in the developing world. Over the next few years demand will revive slowly in the US, not at all in Europe, and it will weaken in the developing world.”

The whole essay is well worth a read. Interesting times.