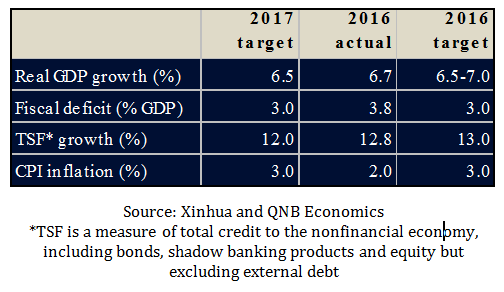

China’s Premier, Li Keqiang, tabled the government’s annual “work report” to the National People’s Congress last week and outlined a range of new economic targets for 2017. The report set a real GDP growth target of 6.5% for 2017, compared with growth of 6.7% in 2016,a fiscal deficit target of 3.0% of GDP and growth of 12% in “total social financing” (TSF, a measure of total credit in the economy). However, we believe that the growth target will not be met if the government implements the fiscal consolidation outline in the work report.

China’s main economic targets

Why do we believe the growth targets are not achievable with the stated fiscal consolidation? The targets imply a growth slowdown of 0.2 percentage points (pps) in 2017. With monetary policy constrained by external vulnerabilities, fiscal policy will be crucial to supporting growth. However, the new deficit target implies a sharp withdrawal of fiscal support. We estimate that the planned fiscal contraction would lower growth by 0.6pps to around 6.1% in 2017. If the government wants to meet its growth targets, it will need to relax its fiscal targets.

Our view is supported by the target for TSF growth. TSF is largely driven by general and quasi government borrowing, including for fiscal operations, and is tightly controlled by central government policy. The government’s new targets imply that the government will continue to stimulate the economy in 2017 through more leverage. TSF growth of 12% is likely to be higher than nominal GDP growth based on the economic targets—real GDP (6.5%) plus inflation (3.0%) comes to 9.5%. In 2016, the government met its growth targets through stimulating the economy with above-target fiscal expansion and TSF growth broadly in line with target. In 2017, a repeat performance seems likely.

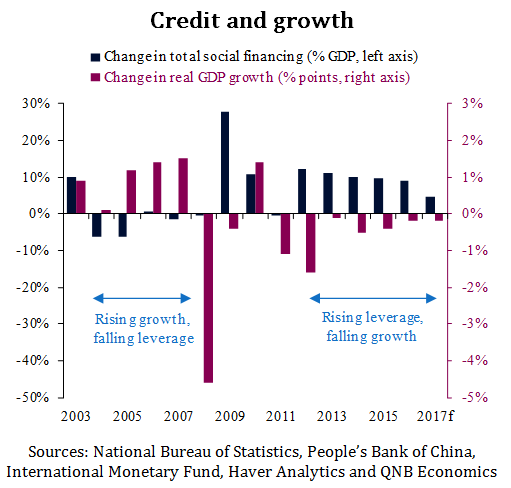

China’s quality of credit is declining, as each additional unit of credit is generating less incremental growth to the economy. Since the financial crisis, leverage has been added to the economy, but growth has been declining persistently, leading to mounting concerns about China’s debt-pile.

Credit and growth

What does this mean for financial stability going forward? Mr Keqiang’s targets imply that TSF is likely to rise from 210% of GDP at the end of 2016 to around 214% of GDP at the end of 2017. This adds to the risk of a debt bust. A fact that the work report alluded when it highlighted that the government should be alert to the buildup of risks related to non-performing assets, bond defaults, shadow banking, and internet finance.

Rising leverage also contributes to other risks. Since 2014, China has been struggling with capital flight and the management of the exchange rate (see our commentary from 19th February, China chooses yuan stability over growth to stem outflows). Rising debt will not help to calm investor nerves and could lead to further capital flight, particularly given that expectations for U.S. rate hikes have risen dramatically in recent weeks. Additionally, rapid credit growth could add to issues of speculation and overheating asset prices. Real estate and equity market valuations are both looking bubbly.

In summary, if the government wants to meet its 6.5% growth target, it will not be able to implement the fiscal consolidation outlined in the work report as this would foment a sharp slowdown. Therefore, the government will continue to stimulate the economy to avoid any potential social unrest. Stimulus will come from relaxed fiscal targets and higher TSF, which will increase leverage. At some point, China will need to deleverage, but it would probably rather do so when the global economy is on a stronger footing and demanding more of China’s exports. Given the recent pick up in global growth, this moment may be soon upon us and China’s deleveraging could become a more prominent theme by 2018.