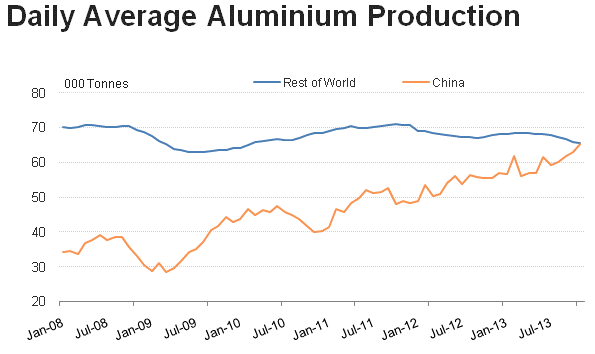

The rise of aluminum production in China has been, in a word, relentless.

National output has risen by 3.36 million tons per year equivalent since the first quarter of 2013, according to Reuters, while that in the rest of the world has shrunk by 1.06 million tons over the same period.

Note, however, that the rest of the world’s loss includes a temporary shutdown of Alcoa’s 370,000-ton-per-year Ma’aden smelter – assume that will restart next year – and that Western world closures have not been as dramatic as they could be.

As Reuters points out, China is now a whisker away from producing half the world’s aluminum, as the graph below shows:

Much of China’s new capacity is being added in the country’s northwest provinces, particularly Xinjian, where a new generation of smelters is being built based on cheap coal-fired electricity production.

The area is a major coal producer, but so geographically remote that it makes more sense to sell coal cheaply for local electricity production than transport it long distances to eastern markets. Power accounts for about 40% of the cost of primary aluminum production and remains the Achilles heel in the economics of Chinese production.

After struggling for a decade to rein in local government support for aluminum producers, Beijing has finally hit on the control mechanism.

The Skinny on Beijing’s Move

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced a range of power costs and related controls that will be applied to all aluminum production from January 2014. Quoting Reuters, power prices will remain unchanged for smelters that do not use more than 13,700 kilowatts (KWs) for each ton of aluminum produced, while those that use between 13,700-13,800 KWs will be charged an additional 0.02 yuan per KW, the article stated.

Smelters that consume more than 13,800 KWs of power for each ton of aluminum produced will be charged an additional 0.08 yuan per KW, and controls have been added preventing local governments from giving fee reductions or other incentives to smelters equipped with their own power production.

Chinese production capacity is said to be in excess of 30 million tons per year, but actual production was only 24 million tons annualized in November; smelters are under intense price pressure and an increase in power costs hits the least efficient (usually oldest and hence most polluting) plants first.

MetalMiner’s Bottom Line

To what extent this will have a significant impact on overall Chinese production remains to be seen, but we suspect the new plants under construction will come on stream at below 13,700 KW/metric ton and hence be exempt from rate increases.

With so much excess capacity in the system, it is unlikely full production capacity will be reached by these measures and oversupply will continue, but having introduced the measures, there is nothing to stop Beijing increasing the rates further or lowering the banding.

It’s about as close as China gets to using the market to control production – Beijing playing the role of Electricity Price-Maker, but allowing plants to run at a loss or close at their own discretion.

by Stuart Burns

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

China Close To Producing Half Of The World's Aluminum

Published 01/02/2014, 02:02 AM

China Close To Producing Half Of The World's Aluminum

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.