China is awash with liquidity. New domestic bank loans have seen some of the strongest growth in years, and broad money supply is increasing at nearly 16% per year. Furthermore, property loans have risen 16.4% from the previous year to 13 trillion yuan ($2 trillion).

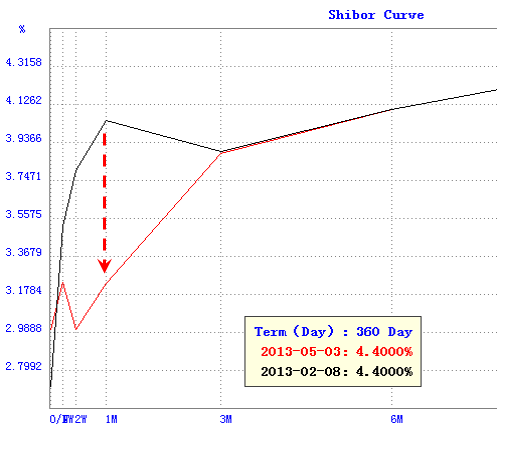

The increased liquidity is now visible in China's money markets, with short-term interbank rates declining in recent months.

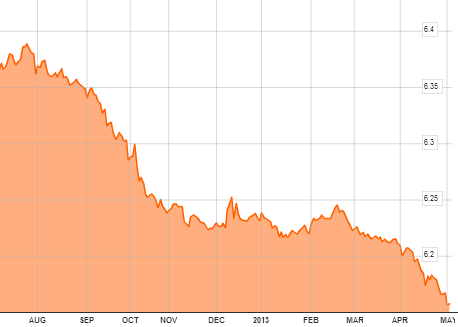

Capital is also pouring in from abroad: investors are attempting to escape the zero-rate environments many developed nations are facing. The demand for yuan has been quite strong, driving the CNY to new record highs.

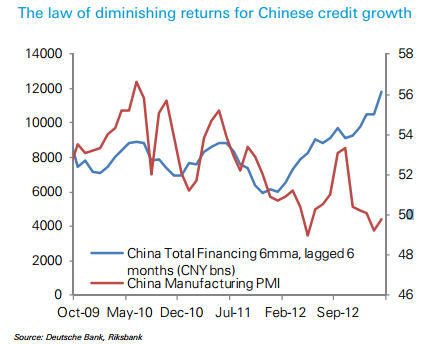

In the past, improved credit/liquidity conditions would result in stronger economic activity, particularly in manufacturing. That's no longer the case.

It seems that China has caught a developed nations' disease in which stimulus no longer translates into improved growth. As was the case in the eurozone, China is suffering from what economists call "weak monetary transmission", a condition in which credit/liquidity is not getting to the areas of the economy where it's most needed (and in some cases there is simply no demand for credit).

DB: - The divergence between hard economic data and the enormous expansion of liquidity since the beginning of the year suggests that credit transmission mechanisms have broken down - and the chances of a credit crunch are growing.

DB calls this the "law of diminishing returns" - more credit doesn't mean stronger growth:

All this liquidity (which started last year) may have avoided a "hard landing", but the bet on a renewed growth spurt for China's stimulus has not worked out so far.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

China's Weak Credit Transmission

Published 05/06/2013, 01:51 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

China's Weak Credit Transmission

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.