Not only do we all have memorize all the acronyms of the financial crisis, "everyone" wants to know about swap lines now; please see our attempt at explaining it in reasonably plain English.

Background: many banks outside the U.S. need to have access to U.S. dollars. European banks, for example, are major players in financing Asian and Emerging market projects, many of which are U.S. dollar denominated. Historically, European banks have issued substantial amounts of U.S. dollar denominated commercial paper that was purchased by U.S. money market funds. As of this summer, this practice received ever more scrutiny (including from us); institutional investors also voted with their feet, unwilling to receive lousy yields in a U.S. money market fund that are exposed to fragile banks in Europe with exposure to peripheral Eurozone countries. The practice has not stopped, but the reduced enthusiasm by U.S. money market funds have made it more expensive for European banks to finance their U.S. dollar needs.

While the central bank intervention is a global one, it is clearly aimed at funding issues of European banks. The Federal Reserve (Fed) then introduced a swap facility with the European Central Bank. That facility allows the European Central Bank (ECB) to borrow U.S. dollars from the Fed, then lend it to their banks. There is no credit or currency risk to the Fed as the counter-party is another central bank. US$2.4 billion are in use at that facility - a tiny amount for central banks.

The move today is far more substantial. Last night, many major banks were downgraded, raising concern at central banks that the cost of credit is going to cripple already fragile markets. The facility put in place caps the premium of obtaining U.S. dollar funding for European (and other non-US) banks have to pay versus U.S. banks. This premium had entered the panic territory of 2008, prompting central banks to act. More specifically:

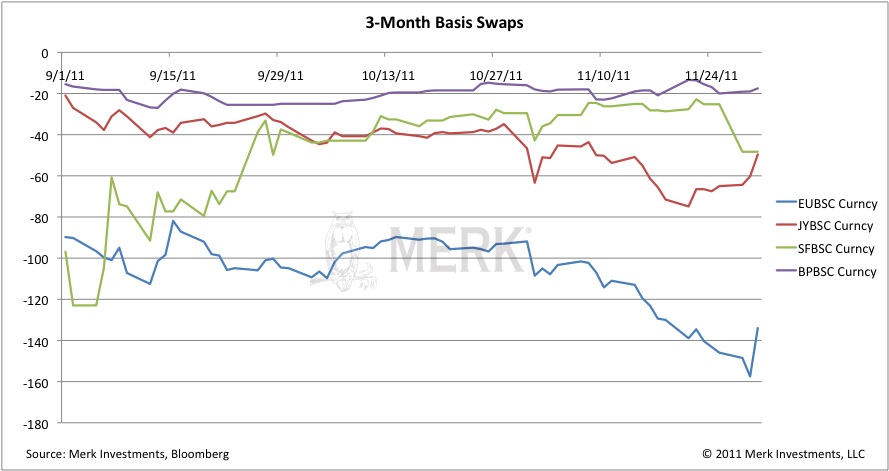

The charts below show the lowered dollar funding costs for European and Japanese banks after the five central banks' joint swap line arrangement.

The blue line is 3 month euro basis swap rate: a negative value represents the premium that European banks are willing to pay to access U.S. dollar funding through the 3 month swap market. The more negative the basis swap rate, the higher the premium that European banks are willing to pay; the higher the dollar funding costs are for European banks. As depicted in the chart, the 3m euro basis swap rate hit -159 bps (100bps are 1%) yesterday, showing that European banks were willing to pay an additional 159 bps more than Libor (London interbank offered rate) to access dollar funding. After today's announcement, the 3m euro basis swap drastically narrowed to around -130 bps. That is, European banks are paying a lower premium to borrow dollars through the swap market.

Similarly, the red line shows that the premium that Japanese banks to borrow dollar through swap markets has also been narrowed. But we didn't see much change in the GBP/USD (purple line) and CHF/USD (green line) swap markets.

In summary, central banks are determined to keep credit markets moving

Background: many banks outside the U.S. need to have access to U.S. dollars. European banks, for example, are major players in financing Asian and Emerging market projects, many of which are U.S. dollar denominated. Historically, European banks have issued substantial amounts of U.S. dollar denominated commercial paper that was purchased by U.S. money market funds. As of this summer, this practice received ever more scrutiny (including from us); institutional investors also voted with their feet, unwilling to receive lousy yields in a U.S. money market fund that are exposed to fragile banks in Europe with exposure to peripheral Eurozone countries. The practice has not stopped, but the reduced enthusiasm by U.S. money market funds have made it more expensive for European banks to finance their U.S. dollar needs.

While the central bank intervention is a global one, it is clearly aimed at funding issues of European banks. The Federal Reserve (Fed) then introduced a swap facility with the European Central Bank. That facility allows the European Central Bank (ECB) to borrow U.S. dollars from the Fed, then lend it to their banks. There is no credit or currency risk to the Fed as the counter-party is another central bank. US$2.4 billion are in use at that facility - a tiny amount for central banks.

The move today is far more substantial. Last night, many major banks were downgraded, raising concern at central banks that the cost of credit is going to cripple already fragile markets. The facility put in place caps the premium of obtaining U.S. dollar funding for European (and other non-US) banks have to pay versus U.S. banks. This premium had entered the panic territory of 2008, prompting central banks to act. More specifically:

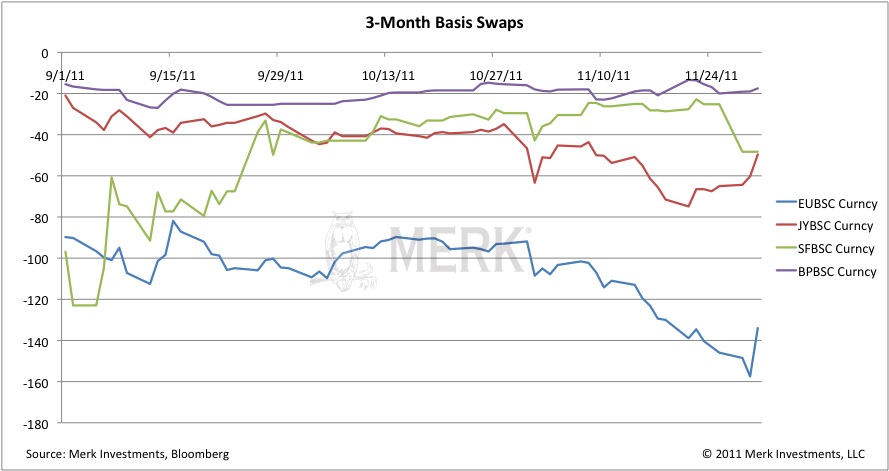

The charts below show the lowered dollar funding costs for European and Japanese banks after the five central banks' joint swap line arrangement.

The blue line is 3 month euro basis swap rate: a negative value represents the premium that European banks are willing to pay to access U.S. dollar funding through the 3 month swap market. The more negative the basis swap rate, the higher the premium that European banks are willing to pay; the higher the dollar funding costs are for European banks. As depicted in the chart, the 3m euro basis swap rate hit -159 bps (100bps are 1%) yesterday, showing that European banks were willing to pay an additional 159 bps more than Libor (London interbank offered rate) to access dollar funding. After today's announcement, the 3m euro basis swap drastically narrowed to around -130 bps. That is, European banks are paying a lower premium to borrow dollars through the swap market.

Similarly, the red line shows that the premium that Japanese banks to borrow dollar through swap markets has also been narrowed. But we didn't see much change in the GBP/USD (purple line) and CHF/USD (green line) swap markets.

In summary, central banks are determined to keep credit markets moving