• Canada is one of the rare countries where the public pension system enjoys a positive net worth that serves to finance current pensions.

• This net worth contributes to lower government debt and thus to confer to Canada a mark of distinction in this regard.

• In response to the declining number of workers per retiree, other countries will certainly be forced to reform their public pension systems in order to reduce their impact on their budgetary expenses and, by the same token, on their debt. Ifnothing is done in Canada in this regard, the positive net worth of the public pension system will gradually be depleted. The system’s sustainability is at risk, as is Canada’s image as a paragon of financial health.

• Given that Canada’s public pension system is already in a net asset situation, the measures that will have to be taken here will no doubt be less painful than those in most of the other countries.

Government gross debt

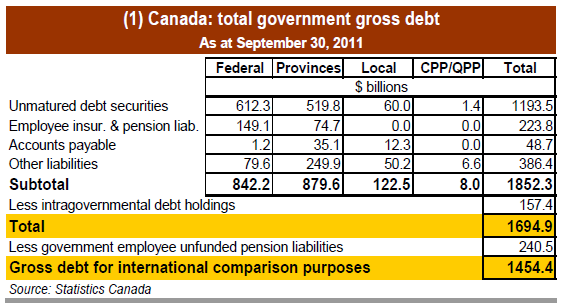

There are a number of concepts of debt that enjoy currency today, serving different purposes. To illustrate this point, let us take the example of the federal government of Canada. To gauge its gross debt, we can opt to use the public accounts or the national balance sheet accounts (NBSA). As at September 30, 2011, federal government gross debt stood at $927.7 billion1 on the basis of the former versus $842.2 billion2 on the basis of the latter. The main difference between the two concepts consists in the fact that the public accounts also include the Exchange Fund Account, liabilities regarding employee and veteran future benefits (other than

pensions) and environmental liabilities.

Hereafter, we will consider gross debt on an NBSA basis. Gross debt is broken down into three principal components: unmatured debt securities, employee life insurance and pension unfunded liabilities (the combination of unmatured debt and employee pension

and life insurance unfunded liabilities is referred to as total interest-bearing debt) and accounts payable and other liabilities.

Then, to compute total government gross debt in Canada, we must add up the gross debt of the federal government3, of provincial and territorial governments, of local governments (municipalities, school boards, and independent funds and organizations), and of the Canada and Quebec pension plans (CPP and QPP). As at September 30, 2011, this debt totalled $1.7 trillion (Table 1).

The quarterly NBSA data published by Statistics Canada allows us to arrive at the subtotal in Table 1 without difficulty. However, as the data on intragovernmental debt holdings are not published, these had to be requested from Statistics Canada.

International comparisons

As we can see, gross debt in Canada is not comprised solely of debt securities issued on the bond and money markets. These make up just under two thirds of the debt. In Canada, the definition of government gross debt takes into account government employee unfunded pension liabilities. As a result, federal government gross debt, like total government gross debt, is over-estimated compared with other countries where these liabilities are not included in the calculation.

This is why, for international comparison purposes, government employee unfunded pension liabilities must be removed from Canada’s public administrations gross debt. Once again, unfunded pension liabilities is not published by Statistics Canada but was provided upon request.

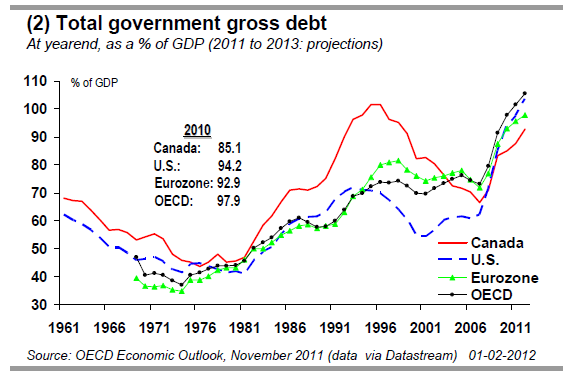

Chart 2 illustrates how the ratio of total government gross debt to GDP has evolved over the past 40 years for Canada and other economic blocs. Canada has not always been the model to follow in this regard, especially when its ratio shot up from 75% in 1990 to over 100% in 1995. However, Canada did manage to adjust its course, so much so that in 2007 its ratio sank to a low of 66.5%. It has of course bounced back since, as it has for all the leading developed countries, on account of measures taken to counter the financial crisis. Still, since 2008, Canada’s ratio has held below that of the major blocs of developed countries.

Net debt

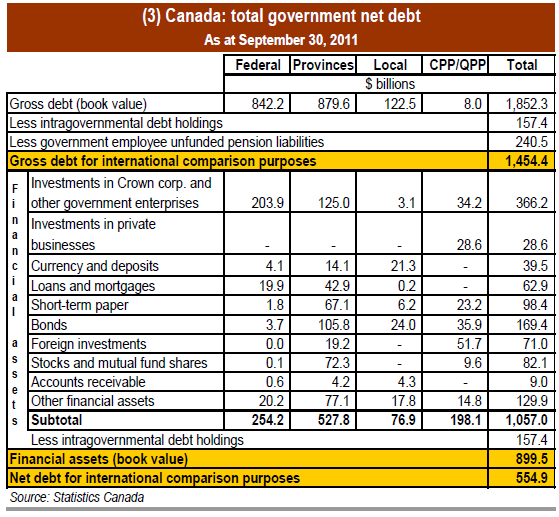

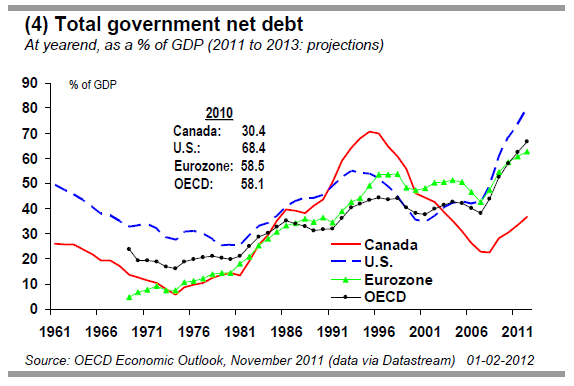

Net debt is defined as gross debt less financial assets. For the purpose of comparing debt levels, net debt is more commonly used than gross debt is. The reason for this is that gross debt can serve as much to finance the acquisition of financial assets as to cover budget deficits. Above all, some levels of government can hold as much in terms of financial assets as they do debt. In most countries, the public pension system uses employee and employer contributions to finance payments to current retirees. This is not the case in Canada and the United States. Indeed, in these two countries, the contributions are invested in financial assets in the aim of financing payments to future retirees. In Canada, as a result of this, the financial assets of the public pension system exceed by far its gross debt. In other words, unlike the government employee pension fund, the public pension system has net financial assets to its credit rather than net liabilities. Thus, in Canada, the public pension system contributes to lower total government net debt. Table 3 allows us to appreciate the extent of this.

Thus, as at September 30, 2011, the financial assets of the public pension system totalled $198.1 billion, against a gross debt of $8.0 billion. Consequently, the public pension system contributed to lower total government net debt by $190.1 billion.

Given that in most countries public pensions are not financed by revenues coming from net assets in pension funds, the difference in favour of Canada in terms of total government indebtedness is more impressive when the measure used is net debt rather than gross debt. This becomes clear when we compare Charts 2 and 4.

For a given country, the difference between the two ratios represents the amount of total government financial assets as a percentage of GDP. At yearend 2010, these assets represented 55.1% of GDP in Canada, compared with only 25.8% in the United States, 34.4% in the eurozone and 39.8% in the OECD countries.

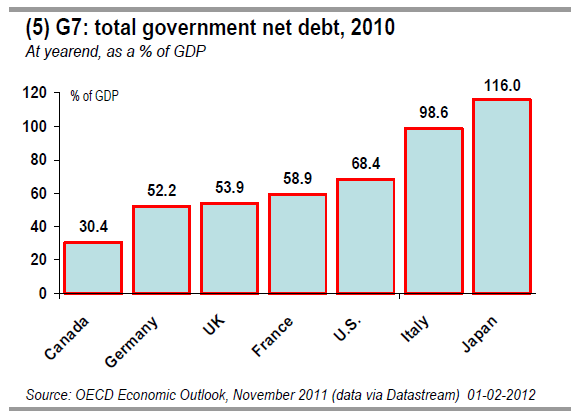

On the basis of net debt, Canadian authorities can boast the lowest total government debt of the G7 countries.

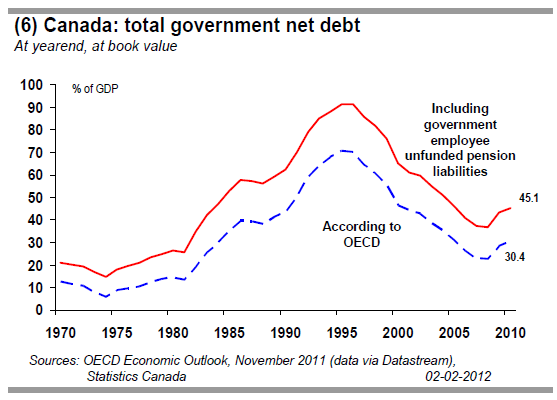

Chart 6 allows us to appreciate the impact on net debt of including government employee unfunded pension liabilities.

In calculating net debt, we considered financial assets at book value to be consistent with the data for other countries published by the OECD. In fact, there is no reason not to use the market value of the financial assets. However, we are not able to arrive at a precise calculation as we do not know the market value of intragovernmental debt holdings. However, we can say that the recent total government debt situation in Canada would come out embellished by such a decision principally on account of a capital gain of nearly $10 billion on intragovernmental debt holdings as at this past September 30.

Debt representing accumulated deficits

When they present their debt levels, the federal government and several provincial governments prefer to calculate gross debt less the value of all of their assets rather than the value of their financial assets only. Given that the acquisition of an asset is a non-budget operation and that the depreciation of non-financial assets (essentially tangible capital assets and inventories) is a budget expense, calculation of the gross debt less total assets gives the portion of the debt that served to finance past budget deficits.

This debt, for which there is no offsetting asset, served exclusively to finance current expenses. As people say, this is debt contracted in order to “pay for the groceries”. This notion corresponds to net worth (or net wealth), which is positive when an entity is in an accumulated surplus situation (assets exceed liabilities) and negative vice versa.

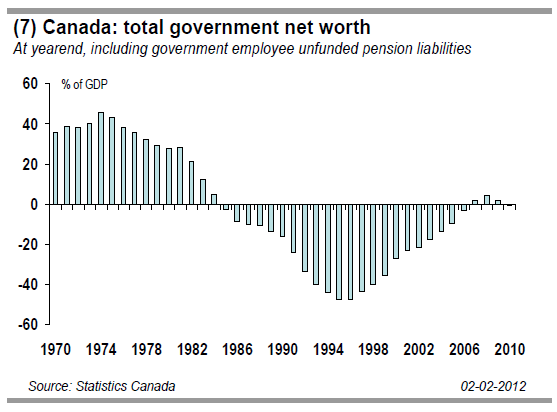

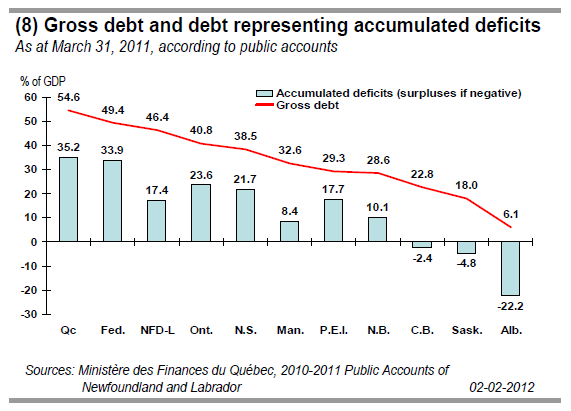

Chart 7 shows the evolution of total government net worth in Canada (including government employee unfunded pension liabilities). It may come as a surprise to find out that governments on the whole were only very slightly in a net liability situation at the close of 2010. We already know that the public pension plans are in an accumulated surplus situation. This is also true of local governments, of which the value of non-financial assets exceeds that of their liabilities. The net worth of these two components is more or less equivalent to the debt representing accumulated deficits for all of the provinces and the federal government. Chart 8 shows the gross debt and the debt representing accumulated deficits (surpluses) on a public accounts basis for these two levels of government.

Quebec is the province with the largest debt on the basis of both gross debt and debt representing accumulated budget deficits. On the other hand, there are three provinces in an accumulated surplus situation, that is, whose assets exceed gross debt.

Conclusion

In Canada, public pension plans are in an accumulated surplus situation. This situation contributes heavily to the fact that total government debt in Canada, measured in terms of net debt for international comparison purposes, is lower on average than in most other industrialized countries.

However, owing to demographic trends, the worker-retiree ratio will go from its present level of 4.4 to 2.4 in 2030, which is in line with projections for all of the OECD countries. At this pace, if nothing is done, the positive net worth of the Canadian public pension system will gradually be depleted.

The other countries will certainly be forced to reform their pension systems in order to reduce their impact on their budgetary expenses and, by the same token, on their debt. If Canada holds its present course, not only the sustainability of the public pension system is at stake, but also the advantage that the country enjoys in terms of the general financial situation of government.

Since Canada’s public pension plans, unlike those of most of the industrialized countries, are already in a net asset situation, the efforts that will be required to maintain their sustainability will no doubt be less painful than those that the citizens of other countries will have to make.

Canada – According to the Labour Force Survey, Canadian employment rose just 2K in January, well below consensus expectations for a 22K gain. The unemployment rate rose one tick to 7.6%. The job gains were all in goods-producing industries (+9.3K), with gains in all subcategories except construction. Services lost 7K jobs including the 23K in the FIRE category and 45K in professional services, those more than offsetting gains in education, trade and info/culture. Full time employment fell 3.6K adding to the losses in December, while part-time employment added 5.9K (although we still haven’t recovered from November’s massive 57K drop in PT employment). Private sector employment rose for the third consecutive month (+ 19.7K). While the overall report was disappointing, the details were a bit better. Note that much of the weakness came from the self employment category (-37K). Paid employment was in fact up 39K (the best tally since June 2011), with a third straight increase in private sector employment. That's somewhat comforting and consistent with economic expansion.

Canadian GDP surprised to the downside in November, falling 0.1% (versus the +0.2% that consensus expected). The goods sector contracted for the second consecutive month primarily due to the 2.5% drop in oil and gas output (reportedly due to maintenance shutdowns). Utilities contracted for the second month in a row in part due to a warmer than seasonal weather. Construction also saw weaker output for the second month running. Those losses more than offset the increased output in manufacturing and mining (latter's output rose for the first time in three months). The services sector’s output expanded 0.1% in the month helped by retailing and accommodation/food services among others which more than offset the decline in wholesaling. With November’s decrease, Q4 GDP is tracking roughly 1.5% annualized, a bit below the BoC’s estimates of 2%. But don't expect Governor Carney to change his stance based on that report alone. There were special and temporary factors at play in November. The maintenance-related shutdowns (which limited oil and gas output) and mild weather (which impacted utility output) have little to do with the state of the economy.

United States – The US labour market added 243K jobs in January according to the non-farm payrolls survey, more than 100K higher than consensus expectations. In January, revisions were made to reflect updated seasonal adjustment factors and an annual benchmark adjustment. So, after revisions, in 2011 there were 1.9 million jobs created in the US (versus old estimate of 1.6 million). The private sectoradded 2.2 million (versus the old estimate of 1.9 million). Private sector employment expanded by 257K jobs in January, following a strong 220K gain, with both the goods and services sectors providing jobs. Government continued to shed jobs in January (-14K). Average hourly earnings rose 0.2%, while hours worked per week was flat at 34.5. Separately, the household survey showed 847K new jobs created. Note that the January data was estimated using population controls reflecting Census 2010, and are therefore not directly comparable to data in prior months. Those gains were enough to lower the unemployment rate two ticks to 8.3%. That's the lowest since February 2009.

The non farm and household surveys are unambiguously bullish and consistent with the declining jobless claims that we've been observing. The private sector has created 840K jobs in the last three months alone according to the non farm payrolls. Aggregate hours are up 2.7% so far in Q1, a deceleration from Q4's 4.5% but consistent with decent growth in the first quarter of Q1. The wage gains will bring some support to consumption spending, a positive for the broader US economy.

Personal income grew 0.5% in December, topping consensus expectations for a 0.4% increase. Personal spending was flat, and one tick below consensus estimates. With income rising faster than spending, the savings rate shot up five ticks to 4%, the highest since August. In real terms, spending fell 0.1%, although it remains healthy on a 3-month annualized basis at 2%. Real disposable income rose 0.3% in December. While the moderation in spending in December will get bears all excited, that has to be looked at cautiously because it comes after three consecutive healthy months. Moreover, consumer mood may have been impacted by Congress-related uncertainties in the month. We don't see the December dip to be the start of a trend, particularly given the strong gains in incomes, employment and savings.

The PCE deflator, preferred by the Fed over the CPI in gauging inflationary pressures, fell two ticks to 2.4% on a year-on-year basis in December. That was a bit higher than consensus expectations. The core PCE deflator rose 0.2% in the month (double consensus expectations), taking the year-on-year rate up one tick to 1.8%. Despite the hotter-than-expected December prices, the PCE deflator remains quite tame at this point, allowing the Fed flexibility in providing more monetary stimulus if deemed necessary.

The Conference Board's index of consumer confidence fell unexpectedly to 61.1 in January (from an upwardly revised 64.8). While the "expectations" component fell only marginally, the "present situation" index saw a large decline to 38.4 (from 46.5). Consumers may have been bothered by Congress dithering on the payroll tax cut extensions in December. The ISM manufacturing index rose a full point to 54.1 in January from a downwardly revised 53.1. The new orders component of the index soared to 57.6, the highest since April 2011. The production index dropped three points to 55.7 while the employment index fell marginally to 54.3 (both of those are still in expansionary territory though). The now leaner and more competitive US manufacturing sector is on a clear uptrend. Forwardlooking indicators like the new orders component of the ISM bode well for production going forward. The January reading is in line with our expectations that the US expanded at a 2% or so pace in Q1.

US business non-farm labor productivity rose 0.7% annualized in the final quarter of 2011, one tick below consensus expectations. The prior quarter was revised down four ticks to 1.9%. The Q4 advance was a result of output (+3.6%) growing a bit faster than hours worked (+2.9%). Unit labour costs rose for the first time in three quarters with a +1.2% print. The productivity gains, while not stellar, are a positive for corporate profits and hiring capabilities.

The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer survey showed that domestic banks had experienced somewhat stronger loan demand in Q4. On the household side, lending standards and demand for loans to purchase residential real estate were reportedly little changed over the fourth quarter on net. The report shows that credit markets remain functional in the U.S.

Euro area – A European fiscal compact was presented this past week. According to the new fiscal compact, “national budgets are required to be in balance or in surplus, a criterion that would be met if the annual structural government deficit (i.e. one that accounts for the business cycle) does not exceed 0.5% of nominal GDP”. This balanced budget rule must be incorporated within one year into the member states' national legal systems, at constitutional level or equivalent. The EU Court of Justice will be able to verify national transposition of the balanced budget rule. Its decision is binding, and can be followed up with a penalty of up to 0.1% of GDP, payable to the European Stability Mechanism. A target for the structural deficit (rather than the overall budget deficit) provides some room to manoeuvre.

In our view, this measure provides enough flexibility to make it palatable to the politicians that must get the accord ratified by their respective governments. This rule is unlikely to provoke a worsening of current austerity measures. For the zone as a whole we note that the current cyclically adjusted deficit is currently expected to be around 1.5% in 2012 and to be near the target of 0.5% in 2013 according to the OECD.

There were some data releases that suggest the eurozone’s GDP contracted in the final quarter of 2011. Spanish GDP shrunk over 1% annualized in that quarter after staying flat in Q3. German retail sales fell 1.4% in December, following a 1% drop in November. Overall, Eurozone retail sales dropped 0.4% in December following a similar decline in the prior month. The zone’s unemployment rate was unchanged at 10.4% in December.

There were, however, some positive readings out of Europe for early 2012. German unemployment rate managed to drop to 6.7% in January (the lowest in over two decades) and the UK’s manufacturing PMI rose more than two points in January to 52.1, i.e. in expansionary territory.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Canada: Measuring Government Debt

Published 02/07/2012, 02:27 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

Canada: Measuring Government Debt

Summary

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.