As the new Liberal Government takes shape, all eyes will be focussed on how it proposes to finance its ambitious agenda . Deficit financing will be at the centre of all discussions concerning jobs and economic growth over the next five years. In its latest Economic and Fiscal Update (November, 2015), Canada's Finance Department recognizes the damage that has already occurred from plunging commodity prices, the deterioration in the country's terms of trade and the worldwide slowdown . The major question facing the Government is: What is the capacity of the Federal finances and the Canadian economy to meet this challenge?

Fiscal Outlook

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) and Finance Canada each produce a fiscal outlook to 2020-21 based upon existing government policy at the time. On balance, there is no material difference between the two forecasts over the next 5 years. PBO average annual deficit is $2.9 billion, ; the Government annual average deficit is $2.7 billion. However, there is a sizable difference in the fiscal year 2020-21. The Government projects a surplus of $ 6.6 billion while the PBO anticipates a deficit of$4.6 billion . The Government forecasts assume a more optimistic forecast for revenues personal and corporate taxes as well from the GST ( national sales tax) .

As with all forecasts, the further out one goes the less reliable are the projections in either direction. For our purposes, we will use the Government’s projections for the period as a whole as a benchmark with which to explore the capacity of the Canadian economy to manage Federal deficits. The analysis would not be materially different had we adopted the PBO figures.

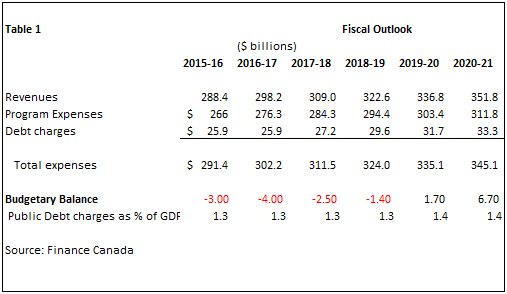

Table 1 is a summary of the fiscal outlook to financial year 2021 prepared by Finance Canada, the department responsible for the national budget. These projects use the former ( Harper) Government fiscal 2015 fiscal framework, update to November 2015. None of the new (Trudeau) Government policies are included.

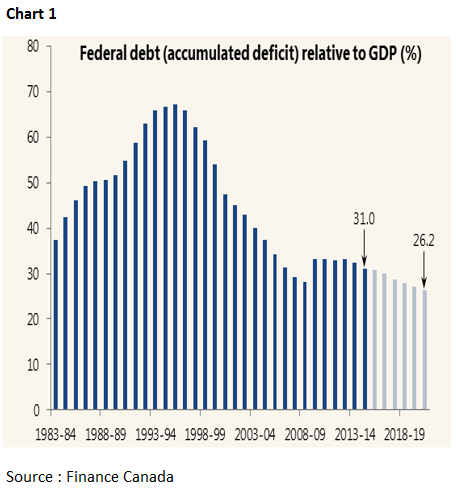

A couple key metrics stand out. First, over the next three years ( 2016-19) the Federal annual deficit will average about 0.1% of GDP--- well within the comfort zone and not out of line historically. Expected economic growth, although modest over the next 5 years, will likely provide sufficient revenues to absorb the annual deficits so that the level of outstanding Federal debt at the end of period remains largely unchanged. Second, the Federal debt outstanding as a percent of GDP actually falls slightly from 31% in 2015/16 to 25.2% by 2020/21. By way of comparison ,the 2021 forecast represent the lowest ratio in over 30 years. ( see Chart 1).

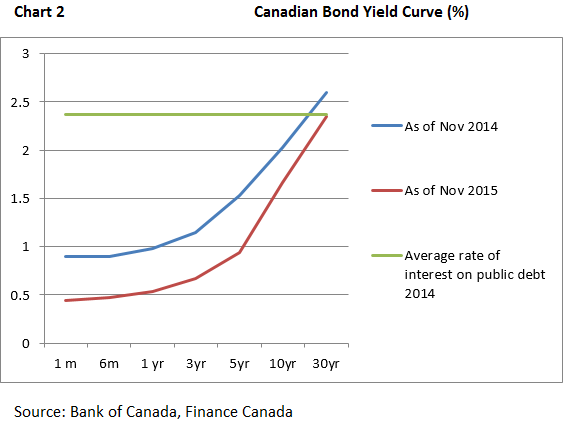

Canada has always been well-received in the capital markets at home and abroad; Bond auctions continue to be well covered and receive firm bids. More importantly, as Chart 2 demonstrates, the entire Canadian government yield curve has shifted downwards in the last 12 months , a reflection of low inflation expectations and confidence in the quality of the security sold. Of late, there has been a shift towards issuing longer dated bonds to take advantage of the falling long term rates (10-Year-30-Year terms). Accordingly, the weighted - average rate of interest on public market debt has fallen to 2.37 per cent in 2013–14. This average interest rate still stands above the current yield for long bonds. Thus, any additional long-term issuance will contribute to a further reduction in average cost of refinancing.

The IMF refers to fiscal space as " the room in the public sector budget that allows government to provide resources for a desire purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position". Canada is in no way jeopardizing the Federal budget by running these anticipated deficits; the size relative to GNP and the servicing costs are well within acceptable range.. More importantly, should the fiscal restraints be relaxed to accommodate additional borrowing aimed at developing infrastructure projects, these projects have the potential to add to future revenues and thus pay for themselves over the longer term.

Comparison to US Stimulus Programs

Parliament opens the first week of December at which time Canadians will learn more of the programs and policies that will constitute the Federal budget and hence the anticipated future deficits. At this point we can assume that the Liberal's platform , featuring infrastructure spending, individual spending programs, and tax changes aimed at the redistribution of income will be at the centre of the next Federal budget. The Liberal party’s platform anticipates a budget deficit not to exceed $10 billion in any year.

American readers should note that what is proposed by the Canadian Government is quite different from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, 2009 (Stimulus Bill) . That bill was designed as an emergency measure to kick start the US economy after the financial crisis of 2008. The main thrust was tax relief for the individuals and corporations to save and create new jobs; a much small component included spending on new infrastructure . A secondary goal was to provide immediate relief to those state and local governments hardest hit by the steep recession. Both countries have adopted a Keynesian approach to stimulate growth; the principal difference is that the US program was conceived as an emergency situation to stop the economic free fall of 2008; the Canadian programs are designed to add to and sustain growth over a longer term.

Shifting the Burden to Fiscal Policy

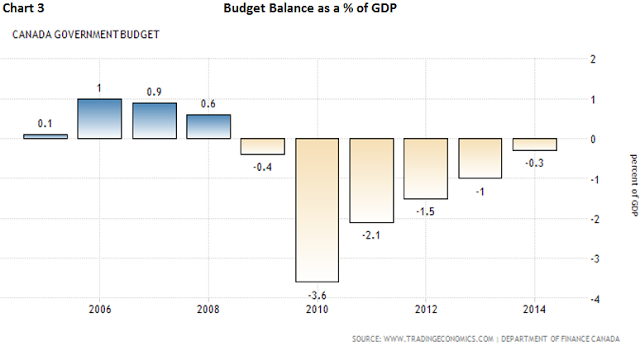

Prior to the 2008 crisis and recession, the Federal Government was running budgetary surpluses; in 2009 all that changed and Ottawa immediately shifted towards deficit financing. However, within a year the previous Conservative (Harper) Government adopted a policy deficit reduction by “starving the beast”, a deliberate policy of squeezing revenues (reduction in the Federal sales tax, GST) and cutting public expenditures (Chart 3). By 2014 the deficits had virtually disappeared. During the recent election campaign arguments were advanced that this relentless reduction in the deficits came at the expense of economic growth.

With the advent of the Trudeau Government deficits will now shift the burden to stimulate the economy away from monetary policy. The Bank of Canada, like all central banks, has been active in reducing the cost of borrowing; in 2015, alone, the Bank rate has been cut from 100 bp to 50bp, largely in response to the swift decline in oil prices and the serious slowdown in the Canadian economy, especially in the spring and summer months.

Moreover, monetary policy has been aided by the 30% decline of the Canadian dollar since 2013. However, monetary policy can do only so much to promote growth. Now, fiscal stimulus will be added to the growth policy mix.