When and where you launch your professional career can mark you for life. For this junior economist joining the ranks of the Department of Finance in the early 1990s, Canada’s future seemed bleak. I wondered how the public would accept the policies being put forward by my employer at the time. The bond vigilantes had had enough of our public-sector spending binge and the time had come for our governments to address the fiscal imbalances. Almost twenty years later, our country is often mentioned as a model of fiscal rectitude, so much so that two credit-rating agencies recently warned the federal government against harming the economy by speeding up the return to a balanced budget.1 In our view, whether the relatively small forecast deficits are eliminated in 2014 or in 2016 does not weigh that much in the grand scheme of things. What does carry weight is the need for another wave of wide-ranging structural reforms that will keep the debt-to-GDP ratio on a downward path after 2015. This cannot be accomplished without a plan to deal with the aging of our population. The challenges set out in 1994 still resonate with us. In contrast to that time, however, our current low indebtedness, fostered by some of the policies introduced since the early 1990s, provides our policymakers (unlike those of some euro-zone countries) with the luxury of time to formulate a smooth transition to a new social contract that will strike a fairer deal among the generations. Canada is in better shape than it was two decades ago, but complacency is not an option. In the 1990s we briefly lost control of our destiny. Today we are well-positioned to avoid reliving that experience.

Progress made

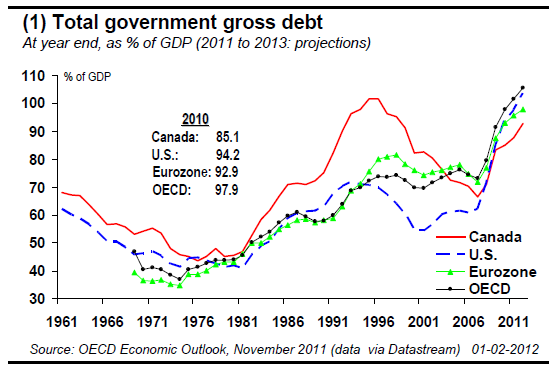

Chart 1 shows how the ratio of total government gross debt to GDP has evolved over the past 40 years for Canada and other economic blocs. Canada has not always been a model in this regard, especially when its ratio shot up from 75% in 1990 to more than 100% in 1995. But when that happened the country did change course, and sharply enough to reduce its ratio to a low of 66.5% in 2007. The debt load has of course bounced back since then, as it has for all the leading developed countries because of the recession and measures taken to counter it. Still, Canada has kept its ratio below those of the major OECD blocs since 2008.

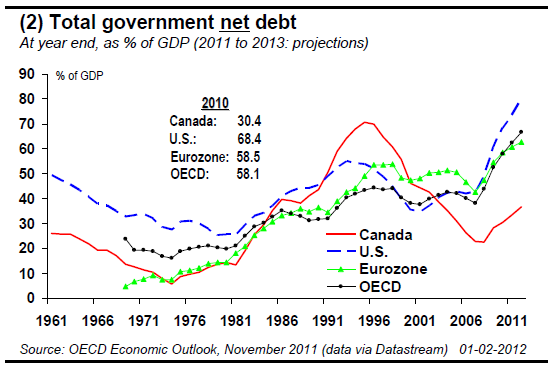

In most countries, however, the public pension system pays current retirees directly from employee and employer contributions (“pay as you go”). This is not the case in Canada and the United States. In these two countries, contributions are invested to fund payments to future retirees. In Canada, since the assets of the public pension system far exceed its gross debt, the public pension system reduces total government net debt. Since most countries pay public pensions from general revenue rather than from a pension fund with net assets, Canada’s total government indebtedness is more impressive relative to other countries when measured on a net rather than a gross basis (chart 2).

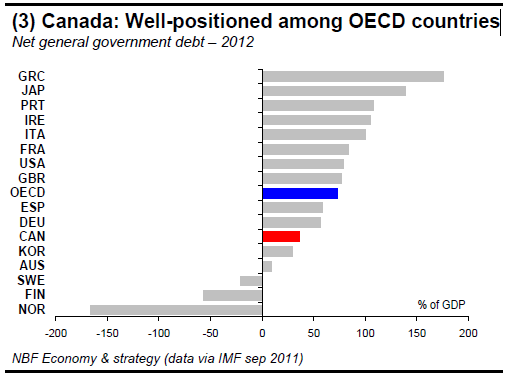

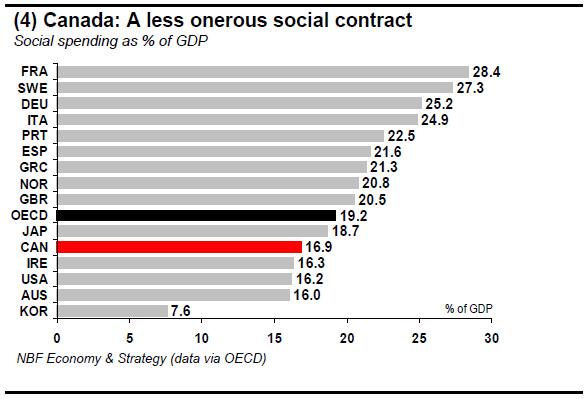

As chart 2 suggests, Canada’s net debt positions it extremely well relative to most OECD countries (chart 3). Looking ahead, it is also important to keep in mind that Canada’s social contract is somewhat less onerous than those of other OECD countries (chart 4), which means that the aging of its population will have less effect on government spending.

Why change?

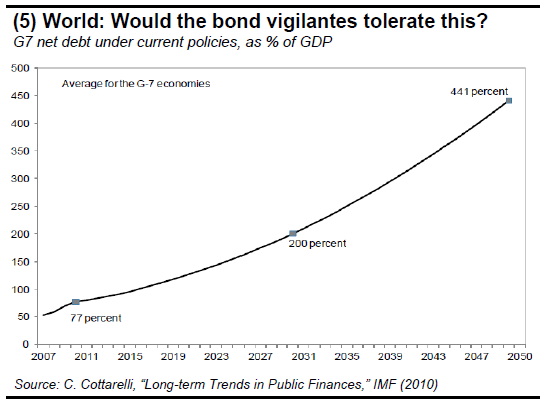

Recent studies published by the IMF reveal the full extent of the challenges gripping policymakers across the OECD. Given that population aging is irreversible, current policies put debt-to-GDP ratios on an explosive path. For the G7 as a whole, these policies would swell general government net debt from the current 77% of GDP to 200% by 2030 and 400% by 2050. You do not need to go out on a limb to say investors are unlikely to tolerate this.

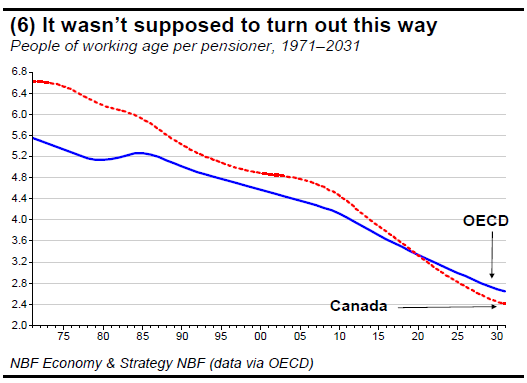

The pressure on public finances comes from one source: rapid aging of the population. When our current social contract was put in place in the 1960s and 1970s, Canada had almost seven workers per pensioner. That ratio is down to 4.4 and headed to 2.4 in less than 20 years (chart 6).

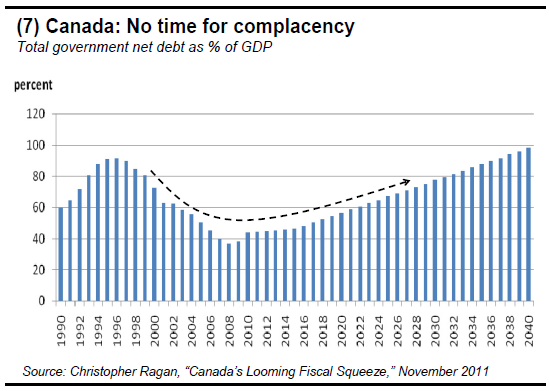

So although our public finances are in relatively good shape right now, this is no time for complacency. A recent study by Christopher Ragan shows that under current policies, Canada’s net-debt-to-GDP ratio will be back to that of the mid-1990s within about 25 years (chart 7). That may be less explosive than in the rest of the G7, but it is a scenario that should not be allowed to materialize.

What should be done?

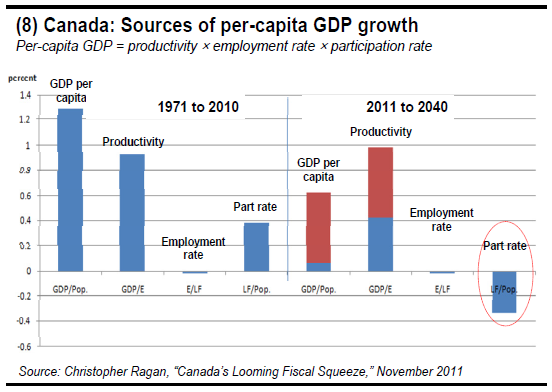

Population aging may be irreversible, but that doesn’t mean its effect on the economy can’t be slowed. One important determinant of economic growth, along with productivity and population growth, is the labour force participation rate. Productivity is of course the holy grail of economists. If we could just find the recipe to boost it, all of our future problems would vanish. Alas, productivity growth can be elusive, not least because of the inherent difficulty of measuring productivity in the aggregate (but we will leave that discussion for another day). Until we have a better understanding of productivity, we think our policymakers should at least concentrate on mitigating the decline of labour force participation. In Ragan’s projection, the drop in Canada’s labour force participation rate from 2011 to 2040 (the drop that would result from continuation of the current rate for each age group) could, under current policies, shave 0.5 percentage points from annual growth of per-capita GDP (chart 8).

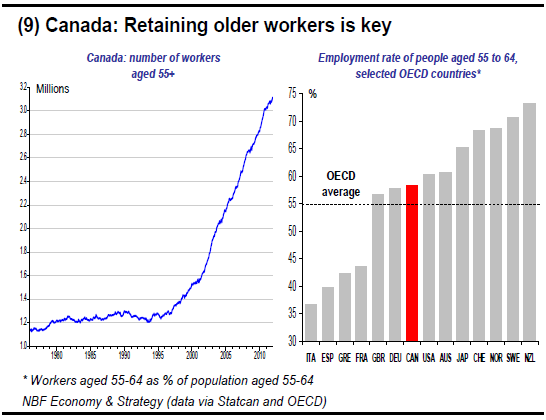

The number of workers aged 55 or older has doubled in Canada in the past decade, to more than three million. Yet as chart 9 shows, the participation rate of Canadians aged 55-64, while above the OECD average, remains well below that of Scandinavia and New Zealand. If we moved closer to them, our GDP growth would be enhanced accordingly.

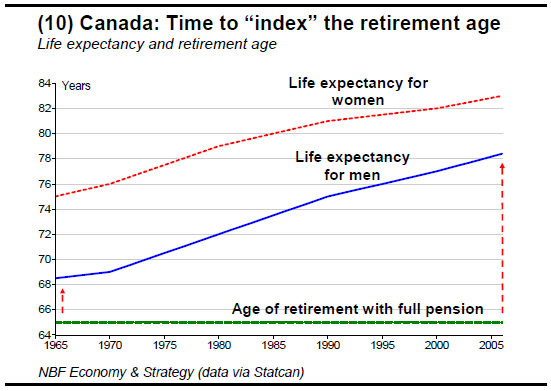

The Scandinavian rates should put to rest the notion that the rate of participation of older workers in the labour force is akin to a misery index. In the 1960s, when public pensions at age 65 were introduced in Canada, life expectancy was 68 for men and 75 for women. It is now 78 for men and 83 for women. In other words, the retirement age has never been indexed to life expectancy (chart 10). This was manageable when the number of workers per retiree was high. That is no longer the case.

Raising the retirement age from 65 to at least 67 is a trend already under way in the OECD (chart 11). In our view, it is time for Canada to join it.

Canada – Canadian GDP growth moderated to 1.8% annualized in the final quarter of last year, in line with the consensus expectation. However, the third quarter was revised up sharply from 3.5% to 4.2% annualized. As expected, trade was a contributor in Q4 – exports grew at 4.6% while imports grew at only 2.1%. Domestic demand

rose at 2.1% in Q4, an improvement from the tepid Q3 showing. It was driven by consumer spending, up a healthy 2.9% annualized on the strength of spending on durables and services after a soft Q3. Business investment in machinery and equipment grew at 2.7% after a steep decline in Q3. Residential construction grew at 3.3%. Inventories subtracted from GDP for a second straight quarter (−1% annualized). The Q4 report showed an expected cooling of growth from Q3, but the upward revision to Q3 and an excellent December reading made it better than expected. For 2011 as a whole, Canada’s GDP expanded 2.5% compared to 1.7% for the United States.

The current account, Canada’s broadest measure of trade, showed a $10.3-billion deficit in Q4, an improvement from $12.3 billion in Q3. The improvement was largely in the merchandise trade account, whose surplus rose to $3.1 billion from $248 million. The services trade deficit widened to $6.2 billion and the investment-income deficit rose more than $0.5 billion to $6 billion. For the year as a whole the current-account deficit was $48.3 billion, a $2.5-billion improvement from 2010.

United States – Durable goods orders fell 4% in January, the largest monthly decline since January 2009 and much worse than the consensus expectation of a 1% drop. Non-defence aircraft orders shrank 19% on the month. As a result, transportation orders fell 6.1%, with improved orders of vehicles and parts easily offset by Boeing's weak order book. Ex transportation, durable goods orders were not as bad but not good, down 3.2%. Nondefence capital goods orders excluding aircraft, a signal of future investment spending, fell 4.5%. Total shipments of durable goods were up 0.4% overall but down 1.1% ex transportation. Shipments of non-defence capital goods ex aircraft were down 3.1%, suggesting a softening of business investment in the first quarter. The unambiguous weakness of the durable goods orders report ends a run of consensustopping U.S. numbers. The expiry of incentives such as the accelerated capital depreciation allowance was probably a factor in the cooling of investment, as was the cloud of uncertainty that still hangs over the global economy.

The latest Conference Board survey shows consumer confidence continuing to improve. From 61.5 in January, the index rose to 70.8 in February, the highest in 12 months. Consumers were more upbeat about both their current situation and the outlook. Asked about jobs, they answered "hard to get" in fewer numbers than in many months (index of 38.7). Eagerness to buy autos was also up from January. Fourth-quarter real GDP growth, initially estimated at 2.8% annualized, was revised up to 3.0%, with larger contributions from consumption and residential construction and slightly smaller drags from nonresidential structures, trade and government relative to the initial estimate. The contribution of inventories was a bit less than initially estimated, which meant that final sales ended up rising 1.1% annualized in Q4. Growth in domestic demand was also 1.1%, two ticks better than in the initial estimate. Q4 was the best U.S. quarter of 2011, thanks to inventory accumulation. So growth is likely to moderate in Q1.

Personal income grew 0.3% in January and spending 0.2%. The savings rate fell one tick to 4.6%. In real terms, spending was flat for the third consecutive month. Real disposable income fell 0.1% after a 0.3% increase in December. The core PCE deflator, preferred by the Fed over the CPI as a gauge of inflationary pressure, rose 0.2%

on the month, keeping the 12-month rate unchanged at 1.9% (the previous month was also revised up one tick). The ISM manufacturing index fell to 52.4 in February from 54.1, the first drop in five months. Its new orders component fell to 54.9 from 57.6. The production index fell marginally to 55.3 and the employment index fell a full point to 53.2 (though both components are still well into expansionary territory). The sub-index for new export orders soared to 59.5, the highest since April 2011, suggesting that global demand is still in decent shape. The ISM reading is consistent with the Beige Book's observations that U.S. manufacturing output continued to ramp up in February. Fed chairman Ben Bernanke gave no indication that further expansion of the Fed balance sheet is on the way. Instead he chose to start his testimony before Congress by stating that the U.S. economy continues to recover and that the available information suggests growth in coming quarters at close to or above the 2.25% pace of the second half of last year. Still, Mr. Bernanke noted that with no substantial declines in the unemployment rate expected this year and

the inflation outlook still subdued, FOMC participants expect that they will be justified in keeping the fed funds rate extremely low into late 2014.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Canada Better Positioned Economically Than in Past Two Decades

Published 03/05/2012, 11:50 PM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

Canada Better Positioned Economically Than in Past Two Decades

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.