One of Wikileaks' most celebrated revelations, in 2011, was a confidential mail from a US diplomat in KSA (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) stating that he had been convinced by a Saudi oil expert named Sadad al-Husseini using data from as far back as 2005 that the nation's oil reserves are overstated by nearly 40%. The diplomat was certain that KSA could not “keep a lid on oil prices”.

To be sure, there was no need to consult Wikileaks or the State Dept to hear that – for at least a decade Matthew Simmons, author of books including Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock published in 2005 has worked the theme of Saudi exaggeration or lying about its oil reserves. Simmons main argument was that over and above the political uncertainty of reliance on Middle Eastern oil, the reserve decline rates for conventional or first-generation oil in the region should raise our awareness of the physical unreliability of Middle East oil. Due to the huge dominance of KSA in Middle East oil and Arab world politics, this firstly concerns the Kingdom before it concerns the rest of the region.

One certain and sure problem is that since the 1980s, sparked by the Iran-Iraq war, Arab OPEC producers in the heavily Saudi-dominated OAPEC organization started regular, usually large and sometimes huge “reserve revisions”. KSA's own recoverable oil reserves depending on what date, as well as what source inside the Kingdom provides the data could range from 250 – 350 billion barrels (250-350 Gb). More bizarre, the reserve number never declines – it only grows despite KSA producing roughly 3.65 Gb-a-year, about 10 million barrels-a-day (Mbd). As reported by the Financial Times June 11, KSA is presently producing “nearly 9.7 Mbd”.

After the 1980s OAPEC round of reserve revisions, only upwards, nearly all other OPEC nations did the same, joined by most major non-OPEC exporters. Consequently there is no “true” unambiguous number for world oil reserves.

UNABLE TO PREVENT PRICE RISES – OR UNWILLING?

What is important to note is that the Saudi oil decline “analysis” can be applied almost word-for-word to joint-No 1 or close No 2 world oil producer Russia. This only underlines that anything concerning world oil and oil prices concerns the Dominant Pair, producing a combined total of about 25% of world total oil output.

In Russia's case, even more than KSA, the role of conventional oil reserves versus “assisted recovery” tapping secondary or tertiary reserves utilising steam-assist, water flood, chemicals, compressed gases and other means to enhance and increase recovery from “tight” source rocks or declining conventional reserves is a constantly moving frontier. This makes the definition of Russia's recoverable oil reserves at least as variable as for KSA but in both cases, and anywhere else in the world – notably US, Canadian and Venezuelan shale oil extraction – higher oil prices expand the recoverable reserves, and lower prices do the opposite.

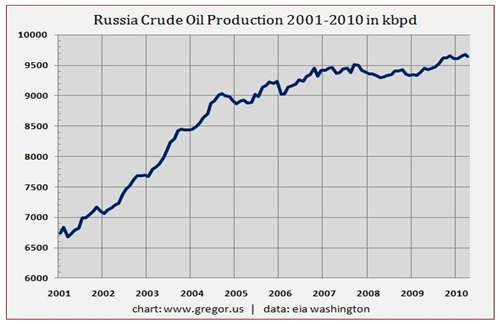

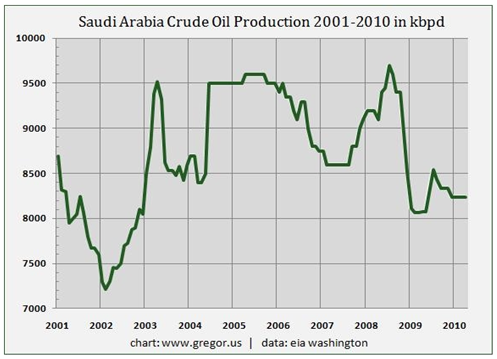

The 2011-vintage Wikileaks revelation has resurfaced as the oil price has soared in recent weeks to well above $100 a barrel, with the main media-friendly explanations being a very slight recovery of global oil demand and above all tensions in the Middle East and Arab North Africa. With totally predictable timing, KSA has announced it will either maintain highest-possible production, or increase it. For as long as this does not prevent oil prices rising, KSA will “almost regrettably” enjoy especially large windfall revenue gains. Russia ditto. Comparison of the dominant pair can start with their ultra-different oil production trends (source: Gregor Macdonald)

As the charts show, Saudi production is “managed” but Russian production is much less compressible, explaining the meaning of the key price setting term: “reserve or spare capacity”. Also, the Saudi chart shows the limits of its wide “discretionary output” capability. The key major difference between KSA and Russia is therefore simple – KSA can “open the tap” provided it has previously cutback output – making the Swing Producer role of KSA one of the most basic, fundamental oil price-setting factors.

Consequently, news and views, opinions and spin on the subject of KSA's production intentions and policies are a must-item for oil market brokers and traders. What we find, possibly not surprisingly, is a permanent shroud of intrigue on these intentions and policies. Reported regularly in all global business media, Ali al-Naimi, oil minister of KSA has since 2007 said the Kingdom has identified projects to increase oil production capacity to 15 Mbd, but since early 2013 Mr Naimi says production capacity will not be increased beyond the current theoretical maximum of 12.5 Mbd “in the next 30 years”. As AFP and other agencies reported from Riyadh, July 28, Saudi billionaire prince Alwaleed bin Talal, a nephew of King Abdullah has warned that global demand for the kingdom's oil is clearly dropping, urging revenue diversification and investment in nuclear and solar energy to cover domestic and local energy consumption. See also my article: http://beforeitsnews.com/energy/2013/07/saudi-royal-sounds-alarm-on-fracking-2450748.html

AND WHAT ABOUT OIL DEMAND?

The OPEC Secretariat – heavily influenced by Saudi views – reported in its monthly report for June that it anticipated “higher demand in absolute terms, primarily due to the structural change in the seasonal pattern”, during the second half of the year, also adding: “The expected global economic recovery in the second half of this year could also add more barrels to seasonally higher global consumption”. Scarcely designed to lend credibility to its oil demand growth forecast it placed at 0.8 Mbd to June 2014, this featured the Secretariat's belief that the summer driving season demand peak would not continue to shrink. It also said: “Growing use of air conditioning in the summer, particularly in the developing countries, has also pushed (forecast) third quarter demand higher”.

Surprisingly or not, the OECD's IEA energy watchdog agency regularly produces reports forecasting imminent increase in global oil demand, very similar to the Secretariat, noting that an 0.8 Mbd increase on current world total demand of about 89.75 Mbd (32.75 Gb per year) would represent an 0.89% increase. One major problem for both the IEA and the OPEC Secretariat, and a plus for Prince Alwaleed is that global oil demand is structurally shrinking – and new oil reserves and resources are available. Overpriced oil, unsurprisingly, encourages conservation and substitution including output from new, previously too-expensive oil sources.

To be sure, global oil demand – except during sequences such as 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 – now rarely changes at a year average rate above 1%. The potential for multi-year zero demand growth is high, signaled by Prince Alwaleed's claim in his six-page letter to his uncle the King and oil minister al-Naimi that world oil demand may attain perfect zero growth by 2015. Risk is supply-side and the deepening intensity of what was Arab Spring but is moving towards Arab Civil War certainly opens the door to supply cutoff risk.

Even as US shale oil output has surged, KSA's discretionary or spare capacity has proven crucial in meeting supply shortages. It raised output during the 2011 civil war in Libya, and in 2012 raised production to a 30-year high slightly above 10 Mbd as US-led sanctions reduced exports from Iran. Saudi action, and posturing in Egypt have the potential for unintended political consequences and the crisis-atmosphere has seeped into Riyadh think tanks and policy parlors. One result is further tightening by Saudi Aramco on the sale of its crude, ensuring only end-users obtain it to restrict their ability to resell barrels, another may be a permanent cap on KSA's maximum capacity.

Overall and due to the total opacity of oil market trading – shown by increasing action by regulators in Europe and the US to rein in abuses – oil prices effectively tell us little or nothing about fundamentals and everything about speculation. Middle East supply risk is however rising, making it likely KSA will keep output at high or very high rates – while “regretting” the high prices that the political risk premium adds to oil. Leaving the last word to al-Naimi, his “preferred market equilibrium price” which has disappeared from all speeches, interviews and comments he gives for over 9 months, was $75 a barrel. At that price level Prince Alwaleed's so-called pessimism is likely unfounded but above it, KSA will go on losing demand volume if not revenues.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Can Saudi Arabia Pump Enough Oil ?

Published 08/15/2013, 07:30 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Can Saudi Arabia Pump Enough Oil ?

PREVENTING OIL SHOCK – OR CAUSING IT

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.