Most of the news surrounding the electricity shutoffs in California—done to avert the ignition of additional wildfires by aging electrical infrastructure—has focused on two things: climate change and the greedy, incompetent management of Pacific Gas & Electric.

Missing in this discussion is the broad neglect of the complex infrastructure of the United States and possibly other wealthy nations. The American Society of Civil Engineers' (ASCE) most recent "Infrastructure Report Card" gave the United States an overall grade of D+. (Those readers unfamiliar with the American system for grading schoolwork should note that "E" is a failing grade.)

While some will point out that the ASCE's assessment is self-interested—civil engineers will, of course, benefit from an uptick in infrastructure spending—the organization hasn't always been this negative about American infrastructure. The 1988 report card wasn't flattering, but it wasn't nearly as dire as the most recent one.

The real question is why, in a supposedly wealthy nation, has the public and private infrastructure been allowed to deteriorate over time?

One answer is that American society has simply chosen to privilege private goods over public ones, a move driven by the increasing individualism of Americans and by the heavy influence of wealthy donors on politicians who make decisions about taxes, especially taxes on the rich, and also about where those taxes are spent. There may be some truth to this though it is worth noting that many wealthy donors rely on government infrastructure contracts for their wealth.

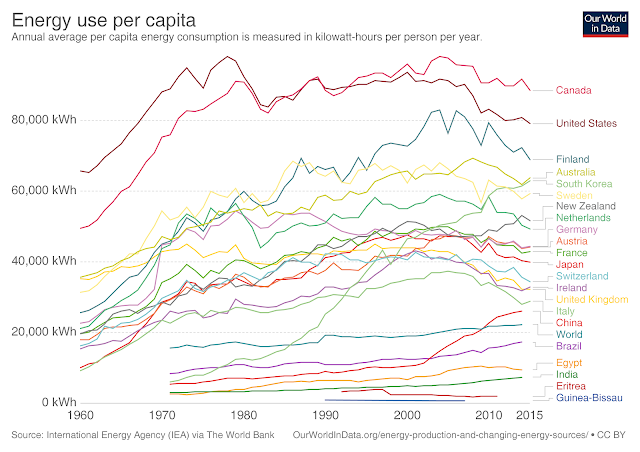

I have been thinking about the possibility that the ongoing decline in per capita energy consumption may offer a partial explanation. Even as overall energy consumption has risen in practically every country over the last three decades, energy use per capita has not. In fact, in the United States and some other advanced economies per capita energy consumption has been falling (or flat) since the early 1980s. This could, of course, be put down to increasing energy efficiency. And, that is certainly part of the story.

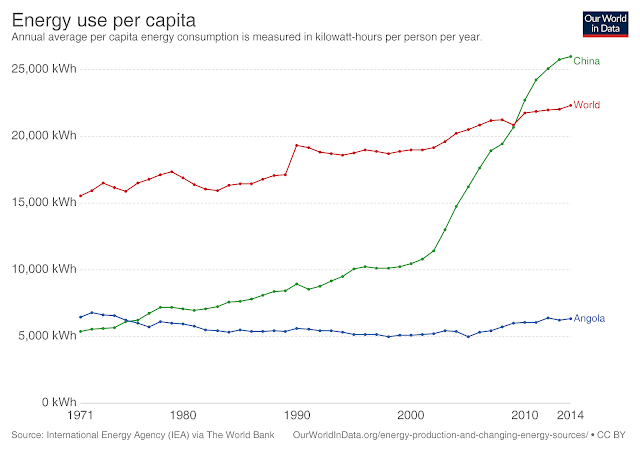

But another part might simply be less energy available per person. The question arises, of course, of whether this is a worldwide phenomenon. Is population growing faster than energy supplies? The overall answer for now seems to be no. Developing nations have been experiencing just the opposite trend though the distribution of these energy riches has been uneven. China's energy use per person has nearly quadrupled since 1980. Angola's has barely budged. And, as we would suspect, the difference in prosperity between the two peoples is notable and extreme.

The thing that strikes me about the history of American infrastructure spending is that it quickened considerably after World War II during a period of very cheap energy. This was the era when the interstate highway system was built, suburbs sprung up everywhere, shopping malls appeared, and schools, universities, hospitals and other public institutions expanded rapidly.

Since the rise in energy prices in the 1970s, the loss of momentum in building new infrastructure is notable. The favorite talk among American politicians has been about curbing profligate spending and reducing public indebtedness. (Austerity in Europe has been an on-again-off-again affair during the same period.) The 1980s and 1990s were an era of low energy prices and yet, per capita energy consumption has traced out a bumpy decline in many wealthy nations right up to this day.

We did, of course, have the biggest bull market in energy in the 2000s through 2008. And, we had the highest average daily prices of oil ever in 2011 through 2013. But prices don't seem to tell the whole story in this case. One possible straw in the wind has been the persistent decline in world oil production since November 2018 even in the face of a growing world economy.

There is no doubt a link between per capita energy consumption and wealth. In fact, wealth is in large part a derivative of energy flows in the economy. If those flows slow down, the ability to get work done—make things, transport them, use them—declines.

The issue surrounding the electric utility infrastructure and the California wildfires is not so much the building of new infrastructure as the maintenance of the existing one. As the complexity and expanse of any infrastructure increases, the cost of maintaining it increases. That means more and more resources must go into maintenance, and that means fewer and fewer resources left over for expansion or profits or both.

If the energy available per capita were continuing to grow in the United States, that would imply a different financial situation. It might have been possible for PG&E to maintain its infrastructure and even upgrade it in the face of the added dangers created by climate change—while simultaneously (and even possibly inordinately) enriching its executives and shareholders.

The fact that the company had to make a choice seems to me to be one indication that our energy future (which is the basis for our economic future) continues to change in ways that suggest only further degradation of the very infrastructure that supports our industrial way of life.