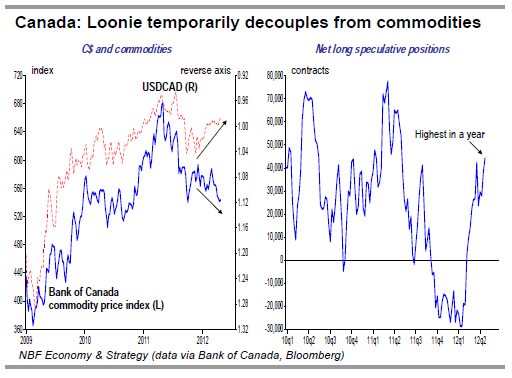

One of the results of the less-austere-than-expectedfederal budget was more flexibility for monetarypolicy. Something had to be done to address what itviews as “the biggest domestic risk”, i.e. householddebt accumulation, and the Bank of Canada seizedthat opportunity with both hands, announcing in itsvery first meeting after the budget was presented,that “some modest withdrawal of the presentconsiderable monetary policy stimulus may becomeappropriate”. That marked a shift in its stance andlanguage which had been quite dovish earlier. And toback its hawkish stance, the BoC presented, in itslatest Monetary Policy Report, strong enough 2012growth forecasts as to allow the output gap to closeearlier than what it anticipated back in January. TheBoC’s more hawkish stance immediately inflated theCanadian dollar, with markets raising bets of ratehikes this year, and speculators increasing their netlong CAD positions to the highest in a year. Thoseforces helped reinforce the loonie’s decoupling fromcommodity prices.

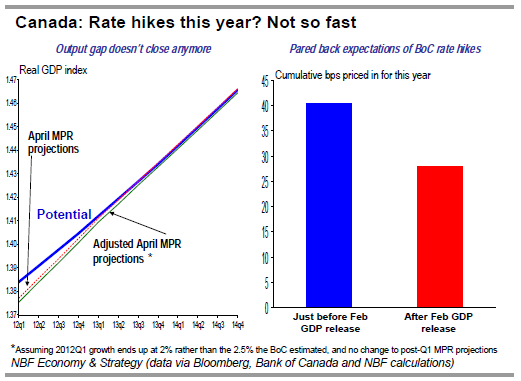

But less than two weeks after the brand new MPRwas released, a disappointing February GDP reportthrew a wrench in the Bank of Canada’s forecast forthe first quarter.

… to dove again?

February’s results were so bad that, barring a miraclein March, Q1 growth will fall well short of the BoC’s2.5% call for the quarter. Even assuming an overlyoptimistic 0.5% increase in March output, Q1 GDPgrowth is likely to print around 2%. So, just howsignificant is a 0.5% miss in the BoC’s Q1 forecast?Assuming no change to the MPR projections after Q1of 2012, the output gap doesn’t close through the projection horizon. While that in itself doesn’t rule outrate hikes, it certainly reduces the probability thisyear ― which explains why markets pared back theirexpectations right after the GDP data was released.

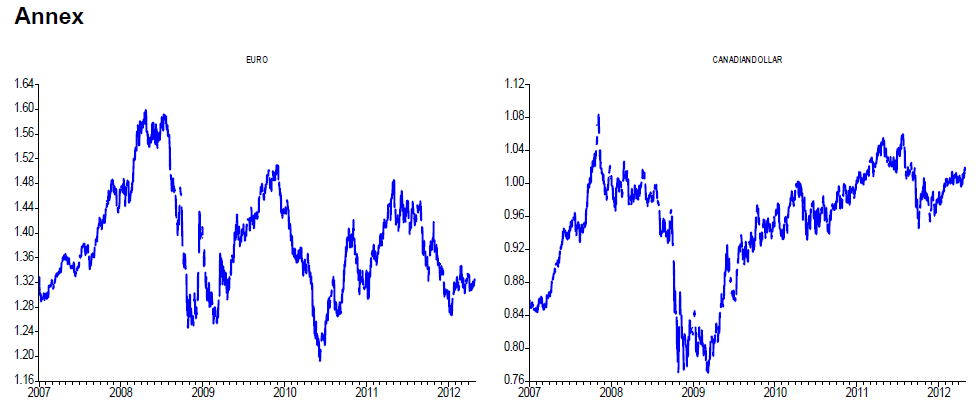

And there’s more than just domestic woes to contendwith. The BoC made clear that “the timing and degreeof any such withdrawal (of stimulus) will be weighedcarefully against domestic and global economicdevelopments”. So, the evolution of the Europeanrecession will also be crucial in determining monetarypolicy at home. Given our slightly more bearish viewon Europe than the BoC and the apparent Q2softening in the US, we continue to expect rate hikesto be delayed until next year. Given what’s still pricedin by markets, that would work as take some steamout of the C$, putting it closer to 1.02 C$/US$ by theend of Q2, a level more consistent with commodityprices.

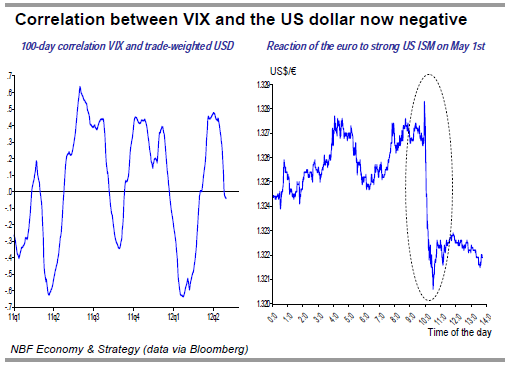

Twisted USD/VIX correlation

Another tailwind allowing the loonie to fly high andfast in April was the underperforming US dollar. Thebig dollar which so often in the past capitalized onnegative global economic news failed to do so inApril. In fact, the US dollar’s correlation with the VIXindex, an indicator of risk aversion, even turnednegative. So, the bad news emanating particularlyfrom Europe isn’t helping the greenback as much.The negative VIX/dollar correlation seems to havecarried over into May with the weak US employmentreports, i.e. April’s non farm payrolls and householdsurveys actually giving a lift to the euro, while a rarepiece of consensus-topping data, i.e. the ISMmanufacturing caused the greenback to rally againstthe common currency.

What’s feeding this negative correlation? One knownfactor helping the euro weather the sea of negativenews is central bank intervention ― the SwissNational Bank has indeed pledged to prevent francappreciation beyond 1.20. Harder to prove is eurobuying by central banks of emerging nations to holddown their own currencies, although that wouldn’tsurprise us given the worsening picture regardingtheir exports to the eurozone.

Another possible explanation for the euro’s surprisingresilience is the repatriation of funds by Europeanfinancial institutions attempting to repair theirrecession-weakened balance sheets. Foreignacquisition of European sovereign bonds may also beplaying a part in supporting the euro.

Euro slump in the car

But for how long can those temporary forces last?The recession is getting worse, not better. Case inpoint is the zone’s manufacturing PMI which fell to45.9 in April, lower than the level recorded lastNovember when credit stress was acute. A readingbelow 50 indicates contraction, not a slowdown ingrowth, meaning that the factory sector is relapsing.

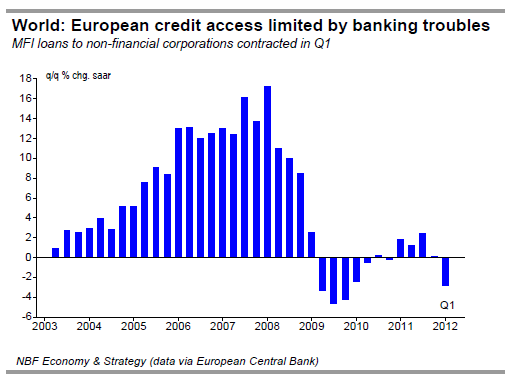

That may be a surprise to some European politicianswho, just a few weeks ago, declared that the worstwas now behind. But the deterioration is hardly asurprise to us. Eurozone demand is being hammeredby a labour market in freefall (ex-Germany) andlimited credit access. Despite the ECB’s liquidityinjections, credit isn’t flowing freely to the economy,as evidenced by the contraction of loans to nonfinancialcorporations in the first quarter of the year.This is what tends to happen when banks are forcedto recapitalize in a recessionary environment.

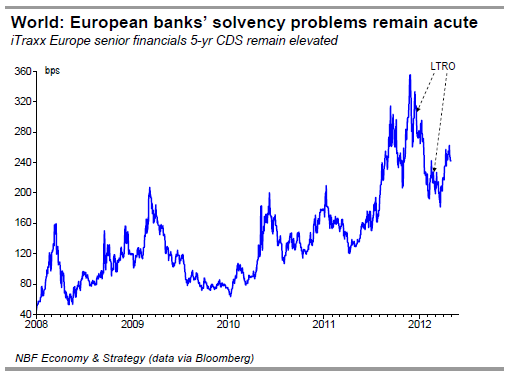

Moreover, bank solvency problems will continue to bean albatross around Europe’s neck. True, the 5-yrCDS on European financials have come down a bitsince the ECB’s long-term refinancing operationsprovided liquidity to cash-strapped banks. But theyremain well above the peaks of 2009 and 2010,highlighting the still-frail state of banks in the commoncurrency area.

Further bank bailouts by European governmentscannot be ruled out, and if those materialize, expectmissed deficit targets and further sovereign ratingsdowngrade. Adding to the fire is political uncertaintywith upcoming elections in France, Greece, and theNetherlands. There will be some challenges toGerman-thinking about how to tackle the currentEuropean downturn. Policymakers are indeed slowlywaking up to the fact that large scale austerityprograms can actually worsen public finances byturning a mild recession into a severe one, andcausing revenues to plummet. What’s needed isstructural reforms to address the long-term path of spending and economic growth, rather than subjectthe economy to short-term cuts that can beparticularly damaging during a recession.

The problem with this, however, is that bond marketstend to punish those who deviate from deficit targets.To avoid those punishing borrowing rates, a countrymay opt to tap the ESM/EFSF. But then again, thelatter is limited in size and meant to be temporaryanyway. So there’s a limited amount of time duringwhich a country can remain shut out of financialmarkets before eventually having to default. Just askGreece. Jointly issued Eurobonds seem best suitedto allow the periphery to borrow at reasonable ratesand hence sustainably finance the necessaryreforms. For now, that option isn’t acceptable toGermany. But expect that issue to return to the tableif, as we expect, the threat of sovereign defaultmakes a comeback.

There’s no quick fix for the European problems. Thetemporary forces that have supported the commoncurrency so far are likely to fade over time. Thecombination of political uncertainty, the ongoingrecession, credit squeeze and bank solvencyproblems, is consistent with deflationary forces,downward revisions for earnings and growthprospects, and further easing of monetary policy bythe ECB. That can’t be good for the euro.

Moreover, consensus expectations look toooptimistic, with GDP contraction estimated at just0.4% and an unemployment rate averaging 10.9%this year. Note that eurozone unemployment wasalready at 10.9% in March and with nine months togo consensus is likely to be disappointed. Underthose circumstances, we remain comfortable with ourcall for the euro to fall to around 1.27 against theUSD by the end of the quarter.

A slowing US economy and the dollar

With the euro likely to return to losing ways, a positive VIX/USD correlation should be restored sooner rather than later. The apparent moderation in global growth should prompt further bouts of risk aversion and give a boost to the greenback in the process.

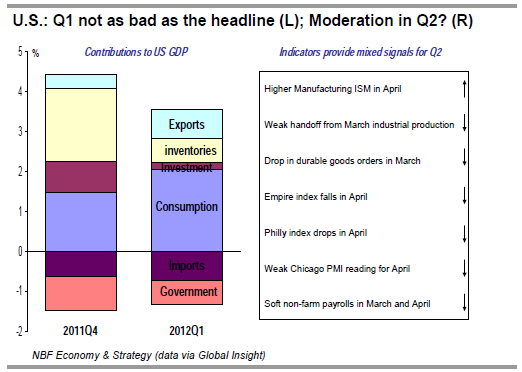

Given how well the US economy has supported theglobal economy by offsetting the drag from Europelate last year, investors may get nervous with theapparent moderation this year. While the details ofthe first quarter GDP report were better than Q4’s,with more vigor in consumption spending andexports, overall growth was weaker at just 2.2% annualized. Preliminary indicators generally suggesta further moderation in the current quarter. But withcontinuing growth, and employment creationremaining in the triple digits, the Fed has resisted athird round of asset purchases, something that hashelped the US dollar somewhat. But if growthdeteriorates more acutely, causing theunemployment rate to climb again, further stimuluscannot be ruled out. The prospect of QE3 is thedownside risk to our forecast for a US dollar rebound.

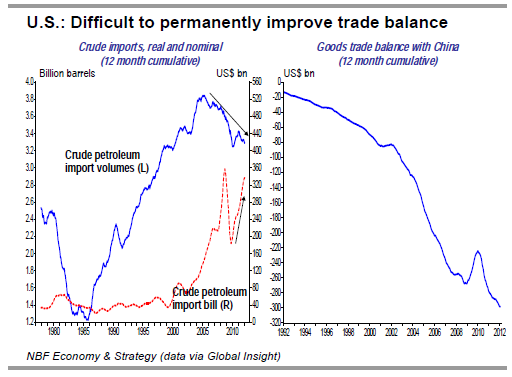

Longer term, the greenback will remain underpressure to depreciate to address America’s tradeimbalance problems. Little progress has been madein reducing the oil trade deficit, with the benefits oflower import volumes of crude oil being largely offsetby higher prices. Moreover, the deficit with Chinacontinues to grow, reaching the highest 12-monthtotal on record in February.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

CAD, EUR, USD Outlook, May 2012

Published 05/07/2012, 04:06 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

CAD, EUR, USD Outlook, May 2012

From dove to hawk…

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.