Followers of the FOMC’s Summary of Projections releases will have noticed a sharp change in the June dot chart from the March chart. No, we are not talking about the downward shift from one to six participants now thinking that one rate move in 2016 will be sufficient to obtain the system’s objectives. Rather, we are talking about the abrupt change in one voting member’s assumption that there should be no change in the FOMC’s target rate in 2017 and 2018. We now know from his subsequent public statements and his recently published paper on the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis website that it was President James Bullard who was responsible.[1]

What's It Mean?

What lies behind this abrupt change in the analytic framework leading to President Bullard’s SEP submission and what does that change mean going forward? President Bullard suggests in his paper that the rationale for his regime-centric approach to policy is simple. He is rejecting the current Phillips curve framework and related empirical models because in his view they have failed: They are mis-specified and do not take into account that the economy swings from one regime to another.

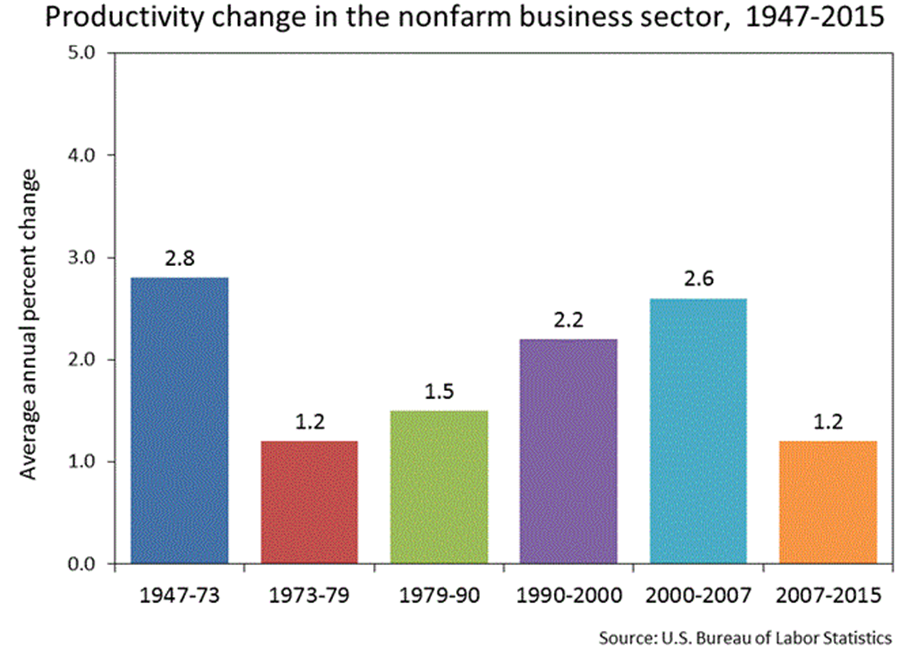

For example, the economy can go from a low-productivity regime, as in 1973–1979, to a high-productivity regime, as in 2000–2007. The chart below shows that there have been several periods when productivity either increased or decreased. Another example he cites is periods of low real returns on government debt versus periods of high returns. The third regime-determining factor is the state of the business cycle – either recession or expansion.

figure 1

In each regime, the relationships among key policy variables can change and models based on the wrong regime can produce monetary policy mistakes. Using models for forecasting purposes that rely upon historical relationships among key economic variables derived over a long period of time, as is the present practice by the Fed and most economists seems to imply that there is a longer-run steady state to which the economy gravitates. But President Bullard rejects this idea and instead suggests that the economy may simply oscillate among different regimes with no long-run steady state. The regime the economy is in, then, conditions the framework and forecasting models to be employed.

No One Knows

But the pièce de résistance of the paper is the argument that one can’t predict when a regime change will occur. Given that conclusion, the best one can hope to do, as President Bullard implies, is to stay the policy course until there is evidence that the economy is in a new regime.

Not considered in the Bullard et al. paper are a number of thorny questions. The first is the empirical question of whether the performance of the current approach and modeling is inferior to that of a regime-specific model. On this question Bullard provides no evidence. In economics we say that it takes a model to beat a model, but a competing model isn’t provided here.

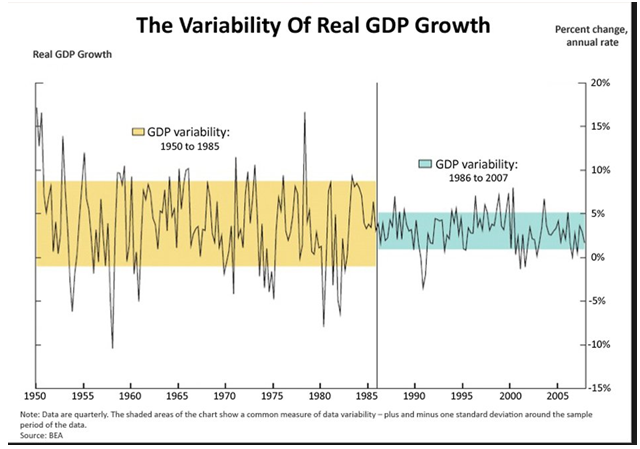

The second question is what criteria should be used to define regimes? Bullard posits three kinds of regimes, but there are other possible choices, such as a low-inflation regime or a high-inflation regime.[2] Regimes might also be defined in terms of the variability of GDP. For example, there was the period of the Great Moderation, shown in Figure 2, during which there was a huge drop in the variability of GDP. Note, too, that the time frames for the two real GDP regimes are different from the potential productivity regimes noted in Figure 1.

figure 2

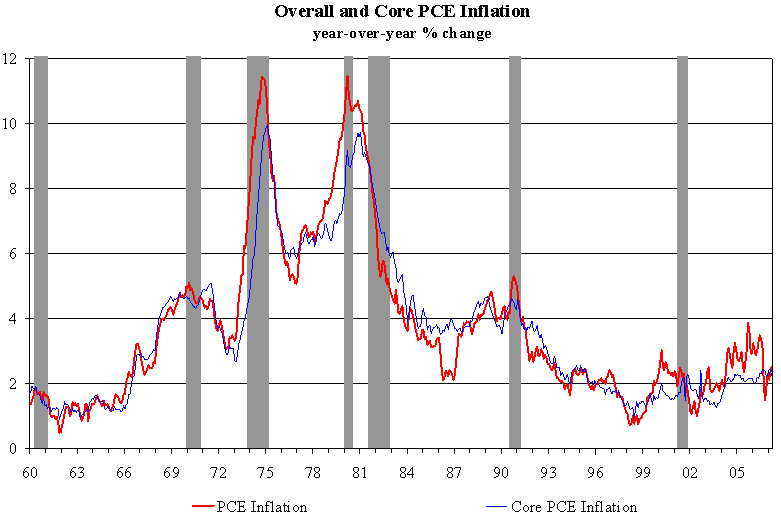

Finally, one might consider defining regimes in terms of inflation, as in Figure 3. There is a potential inflation regime for the early 1960s, a period of rapidly increasing inflation from 1966 through mid-1970s, a period of declining inflation in the 1980s, and a period of low inflation in the first half of the 2000s.

figure 3

Again, it is an empirical question as to which modeling approach can deliver better performance and policy. Lastly, there is the problem that policy makers may not know that a regime has shifted until several quarters have passed. In the meantime, the wrong regime models and policy prescriptions would be applied. This dilemma is only exacerbated by the lags between changes in policy and when they begin to take effect. In short, the regime-shifting approach to policy being advocated carries with it problems arguably little different from the problems being experienced now. We know that Fed staff employ many models and their forecasts reflect a combination of projections from those models, augmented by a healthy dose of judgment. When policy makers are in a world that is not reflected in past data, then their “out of sample” forecasts are bound to have large confidence intervals surrounding the estimates.

Similarly, when a regime shift takes place as President Bullard argues, one doesn’t know whether a new regime is similar to a past regime or whether it is something totally new. In the former case, past models may provide guidance; but if the regime is has no precedents, then it may not be possible to use empirical models at all to guide policy. So we conclude that President Bullard’s approach may not solve the problem of forecast errors, nor may it lead to more enlightened policy.

One last point about the dot chart: we now know that President Bullard was among one of the six dots projecting only one policy move in 2016. Moreover, because President Rosengren, who has been very dovish in his policy approach, is also a voting member of the FOMC, it is likely that he too is one of the six dots favoring only one move in 2016. If so, then at least one, and possibly two, of the five sitting governors or President Dudley is now favoring two rate hikes in 2016. Thus the consensus among the Board of Governors may not be as tight as it has been.

[1] See Regime Switching Forecasts

[2] An interesting point here is that President Bullard also rejects the Committee’s focus on headline PCE as the appropriate measure of inflation, and instead he will now use the Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean PCE as his measure.

Robert Eisenbeis, Ph.D.

Cumberland Advisors Vice Chairman and Chief Monetary Economist