Brazil is another one of those topics which doesn’t seem to merit much scrutiny apart from morbid curiosity. Like swap spreads or Japanese bank currency redistribution tendencies, it is sometimes hard to see the connection for US-based or just generically DM investors. Unless you set out to buy an emerging market ETF heavily weighted in the direction of South America, Brazil’s problems can seem a world away.

It starts with Brazil’s history, most of which has found its economy in one kind of disarray or another. Such makes it very easy to just dismiss their current struggles as reversion to the mean, Brazil getting back to being Brazil. The relevance isn’t immediately apparent.

As late as 1990, for example, the biggest country in South America was gripped by runaway inflation. In March 1990, Brazil’s CPI registered 82.39% inflation – in just that one month. Year-over-year, consumer prices were up an astounding 6,390.52% that March. For the year 1990 as a whole, inflation would average a little more than 4,100%.

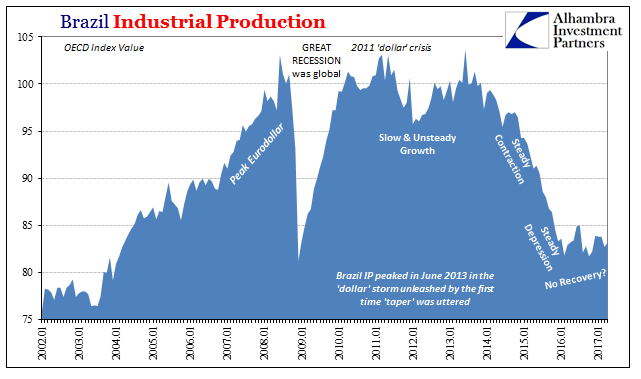

If Brazil slips again into an economic coma it may not seem all that noteworthy. But in between the nation was completely transformed, remaking itself into an economic powerhouse. In 1990, their output was about half that of the United Kingdom; by 2011, the Brazilian economy had surpassed the UK’s and took its spot in 7th place globally. It was the envy of all, the B in BRIC.

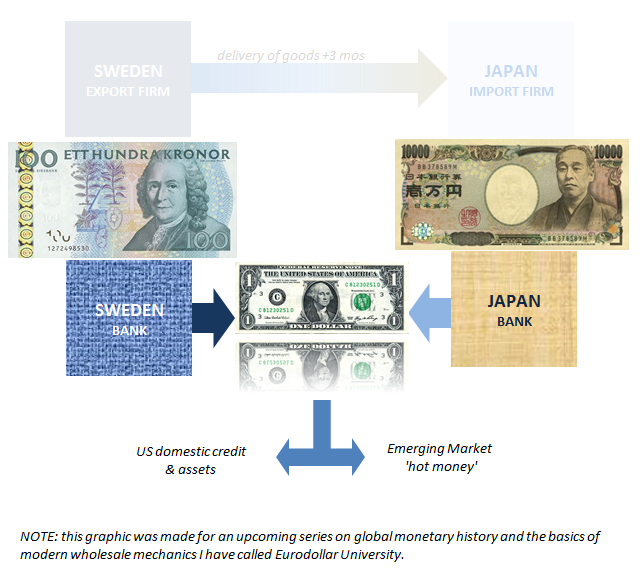

Though that growth, like China’s and all the EM’s, has been classified as a miracle it never really was. Orthodox economics assumes that each of these economies are closed systems with minimal interaction between them. That allowed, essentially, an entire unexamined monetary system to develop without official acknowledgement, building up at exactly the same moment as all these economic marvels. Some may argue with the characterization, but I don’t think it all unreasonable to suggest the eurodollar built these places.

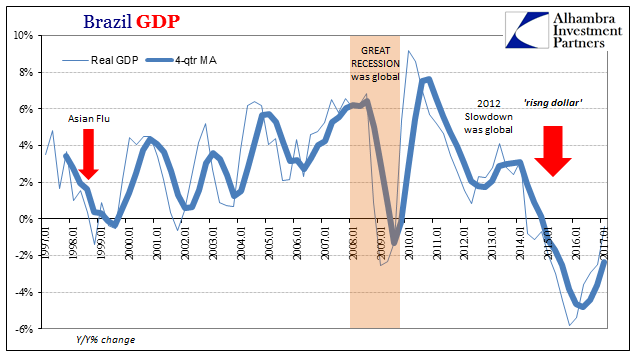

And since 2011 it has been tearing them down to one degree or another. This part of South America has experienced some of the worst of it, an extreme example. If they had been true periods of unconstrained expansion in wealth, these systems wouldn’t be so susceptible to negative monetary conditions especially the last few years. Many of them have been ruined, like Brazil’s, as the tide of the eurodollar has only receded. It can’t have been a miracle it if it so easily and so thoroughly undone.

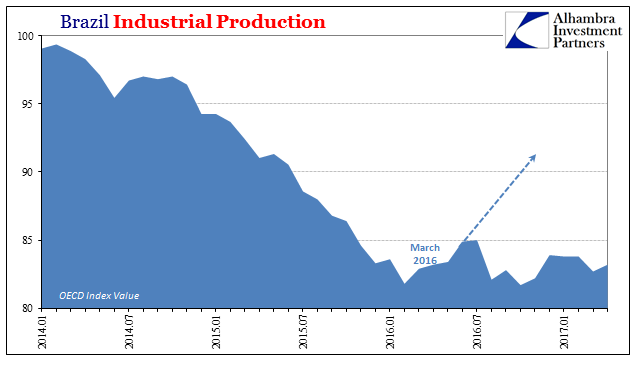

Having been devastated by the “rising dollar”, we search now through its economy for what it might look like without further monetary destruction. The currency, which had been trashed for years, has rebounded. There has been in the past year a window for recovery. In that recovery we might find parallels to our own case.

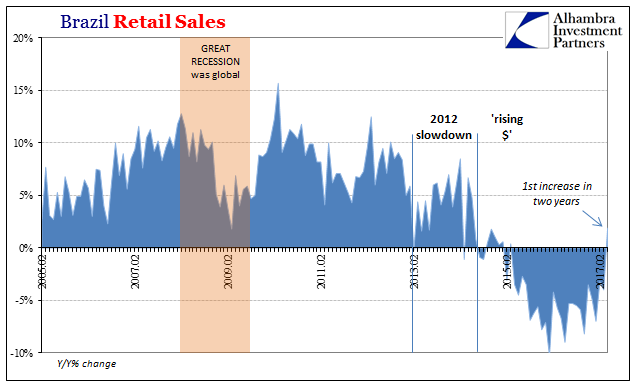

In April 2017, the latest figures available, Brazilian retail sales rose year-over-year for the first time since March 2015. Gaining 1.9% above April 2016, many have attributed the switch to a plus sign as evidence of a change in fortune. Though real GDP has contracted for three years without a break, in Q1 2017 it was for the first time also in two years nearly flat year-over-year.

But this restoration of plus signs now and in the near future (real GDP growth in Q2 will likely be positive) betrays what has really taken shape down there. After the worst economic circumstances in almost three decades, Brazil’s economy should be roaring back to life in dramatic fashion; not tepid advances in a few statistics here and there. It is that last product that is alarmingly familiar.

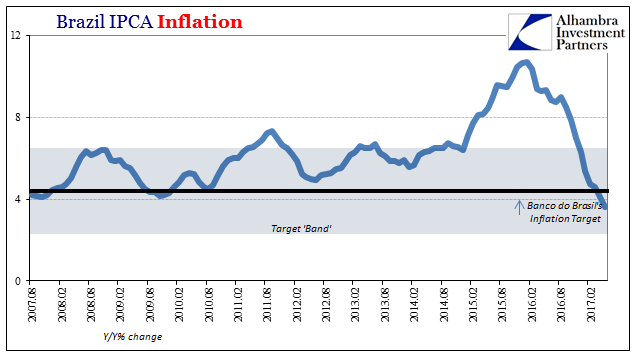

For the most part, retail sales in particular, the better results are due to the currency translation and therefore a falling inflation rate. The real devastation in Brazil’s economy the past few years was the dual impact of the global downturn on demand as well as the internal difficulties with rapid inflation.

With the currency more buoyant without the direct “rising dollar” influence, together with economic destruction, consumer price inflation has receded to the lowest level in ten years. Half of the Brazilian economy’s worst problems has been eliminated. The other half, however, has not.

There is as yet no turnaround in sight for global demand, though there has been now more than enough time for one to have developed. Given Brazil’s prominent place in the worldwide economic chain, it would be strongly evident there first. It is this absence that helps explain the meandering rebound overall, rather than a full-throated recovery as would be expected after so much and so heavy contraction.

Things are better in the sense that the monetary difficulties have for now withdrawn. Things are not better in the sense that having undergone so much depression for so long it seems as if Brazil’s economy simply shrunk. The bearing and relationship of the global economy is what is of our immediate concern.

Brazil’s modern economy was made by eurodollars, and as that global currency erodes it has unmade Brazil’s economy. It is an extreme example but nonetheless instructive.