A funny thing happened on the way to inflation... Long-term Treasury yields failed to rise as well. And although the shadow of the markets reaction is short relative to the daylight provided, the conundrum that became the long-term US Treasury market over the past 20 years appears to be penning a new chapter in how to fool the consensus at the expense of conventional market wisdom. That being said, we do sympathize with those participants perennially hood-winked trying to connect the dots in a market environment under the influence of multi-generational trends and a transparent Fed navigating difficult and esoteric terrain.

While it likely comes as a surprise to most participants -- and we suspect many remain bias towards a rising yield environment in the face of inflation, to a large degree the market climate running into 2014 provided the conditions necessary to illicit what we perceive to be a rational market reaction of what some might describe as an irrational market response. The bottom line is that the perception of rationality - like time, is a relative expression.

A basic understanding of the phenomenon of inflation is that it is to the bond market as kryptonite is to Superman. The greater inflation risk, the worst the bond market performs -- as investors will demand a higher yield to compensate for greater inflation risk.

Last week we received the May CPI data that further confirmed what we had already suspected -- that inflation was beginning to accelerate. From Deutsche Bank:...Janet Yellen dismissed the recent rise in inflation as "noisy" data. But if randomness is at play we can calculate some odds. It is ten years since American consumers have seen core prices rising faster than the current 0.3 per cent monthly rate, double the average over this period. Based on the volatility of the data there was only a 5 per cent chance of inflation being this high. For context an equivalent 1.7 sigma event would be 6 per cent annualized growth in quarterly output, or payrolls adding 500,000 jobs in one month - both occurring just once in the last decade...

So why wasn't there a strong reaction in the bond market if inflation is starting to surprise on the upside?

We believe that where a complicated market becomes even more so, is when one considers 1.) the relative extreme in yields that was reached at the end of last year, 2.) the uniqueness of the capital markets relative to what the Fed has provided over the past five years; and 3.) the rear-view proximity, density and casualties in participants memories to the spectrum of financial bubbles and crises from LTCM to GFC.

All told, we believe current market conditions will at the very least place a governor on the impetus for rising long-term yields despite the fact that inflation is starting to pulse strongly through the system.

#1 - Relative Extreme

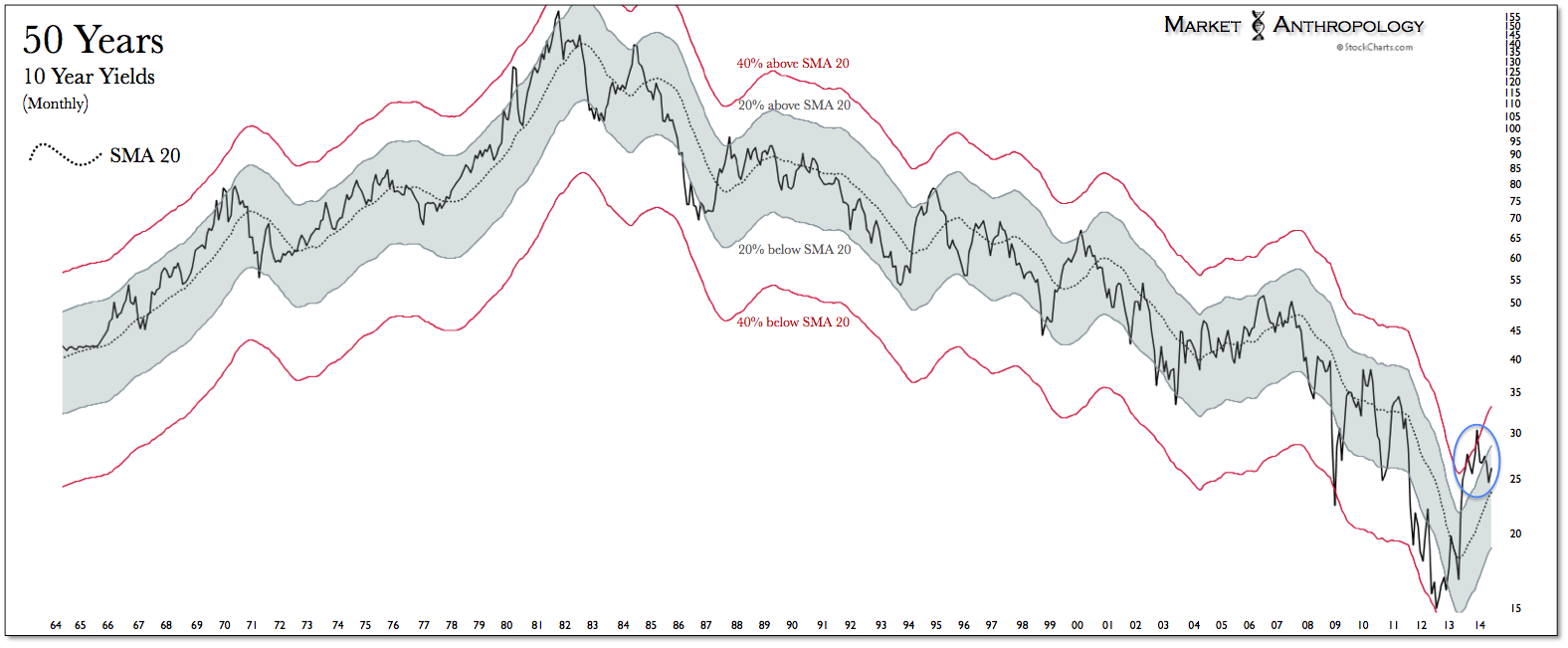

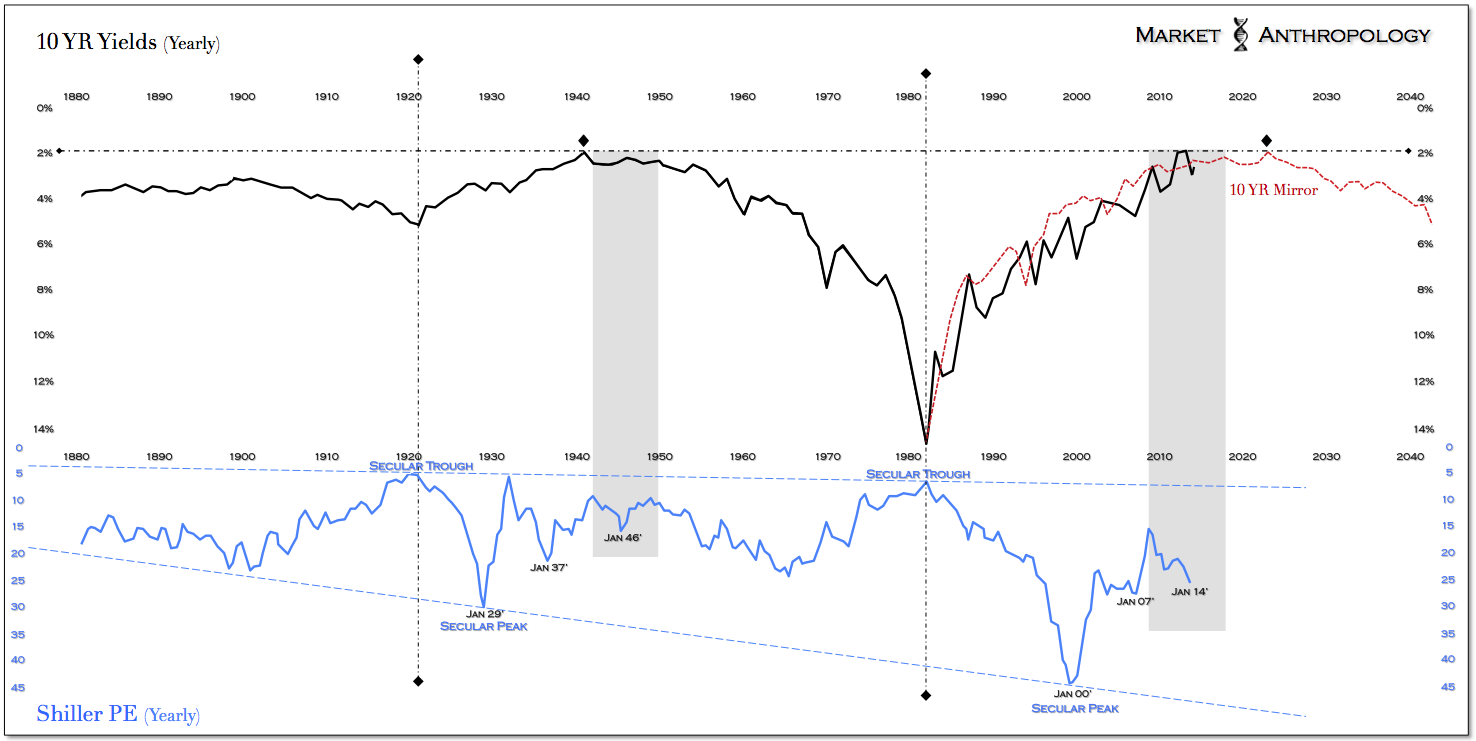

While we have never claimed to be experts on the nuances and intricacies of the US Treasury market, we do bring a thorough historic evaluation of trend and performance of some of the larger asset pistons and gear exchanges that help propel the system forward. Broadly speaking, this provides a comparative bearing to triangulate market strategy from of what we believe lies just ahead on the horizon. Going into 2014, we anticipated that long-term Treasury yields would pull back from the relative extreme they notched at the end of last year. Despite their historically low disposition, the talk of the taper that began in earnest last May spooked the bond market and elicited a rally in yields -- the surprisingly magnitude of which was likely discretely lost on many. Here's a quick snippet from a previous note that sets the stage.

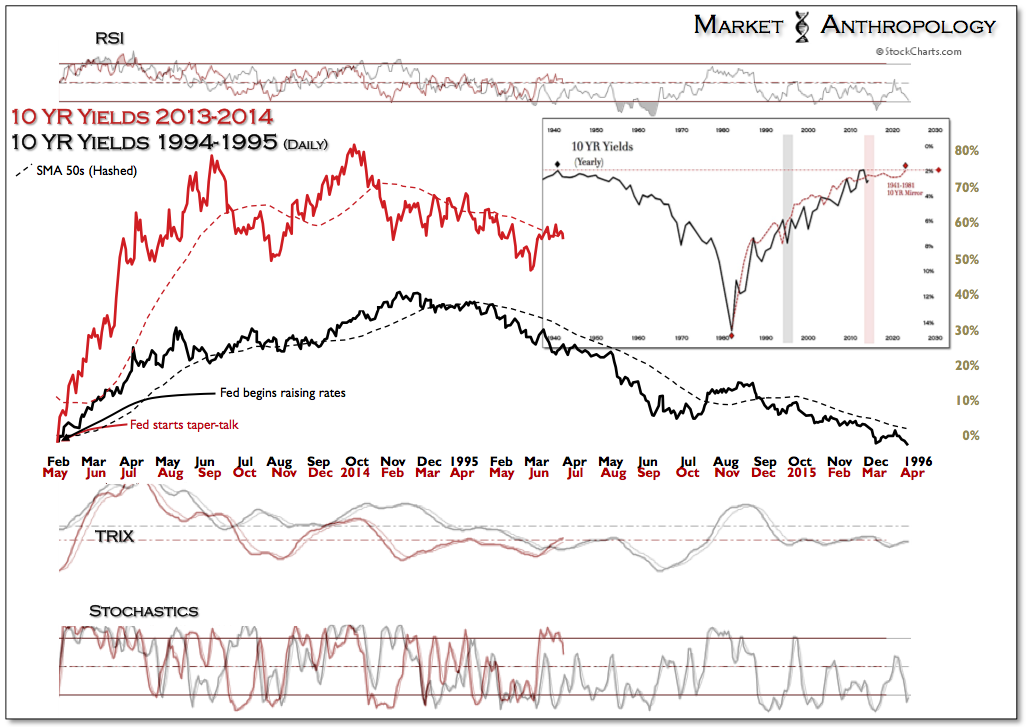

...Even when contrasting the bond market carnage in 1994 - brought on by the commencement of an unexpected Fed tightening cycle, the move in 10-year yields over the past year has been twice its magnitude. When viewed as a comparative study between these two time periods (normalized below by the month over month performance) you can see that even during an actual Fed rate tightening period in which the fed funds rate doubled from 3% in February of 1994 to 6% in February of 1995, 10-year yields crested only ~ 40% above the previous years low and started breaking down during the Fed's final rate hike in February of 1995. To put the move in even greater context, 10-year yields appreciated just shy of 70% from the entirety of the previous cycle low in June 2003 to the cyclical peak in June 2006. This encompassed a Fed rate tightening cycle which took the fed funds rate gradually from 1.0% in June 2004 to 5.25% in June 2006... - Perspective 4/30/2014

Where that leaves us currently is in the doldrums between the downside pivot in long-term yields

that began at the start of this year and the next move we still expect will be lower along the arc of the 1995 return. Helping things through the pivot this year has been a consistent imbalance extreme with respect to sentiment and positioning in the long-term Treasury market. E.g. at the start of the month with the move in the falling close to 20% to ~ 2.40% for the year, a J P Morgan Chase & Co (NYSE:) client survey indicated the difference between the number of investors who said they are bearish on US long-term Treasuries exceeded those who are bullish grew to its highest level since May 2006 -- one month prior to the previous cycle peak for yields in June of that year.

#2 - The Hand of the Fed

While most market research has been fixated on comparative bearings with more recent Fed rate tightening cycles and when the Fed would commence this rate tightening regime, they have largely

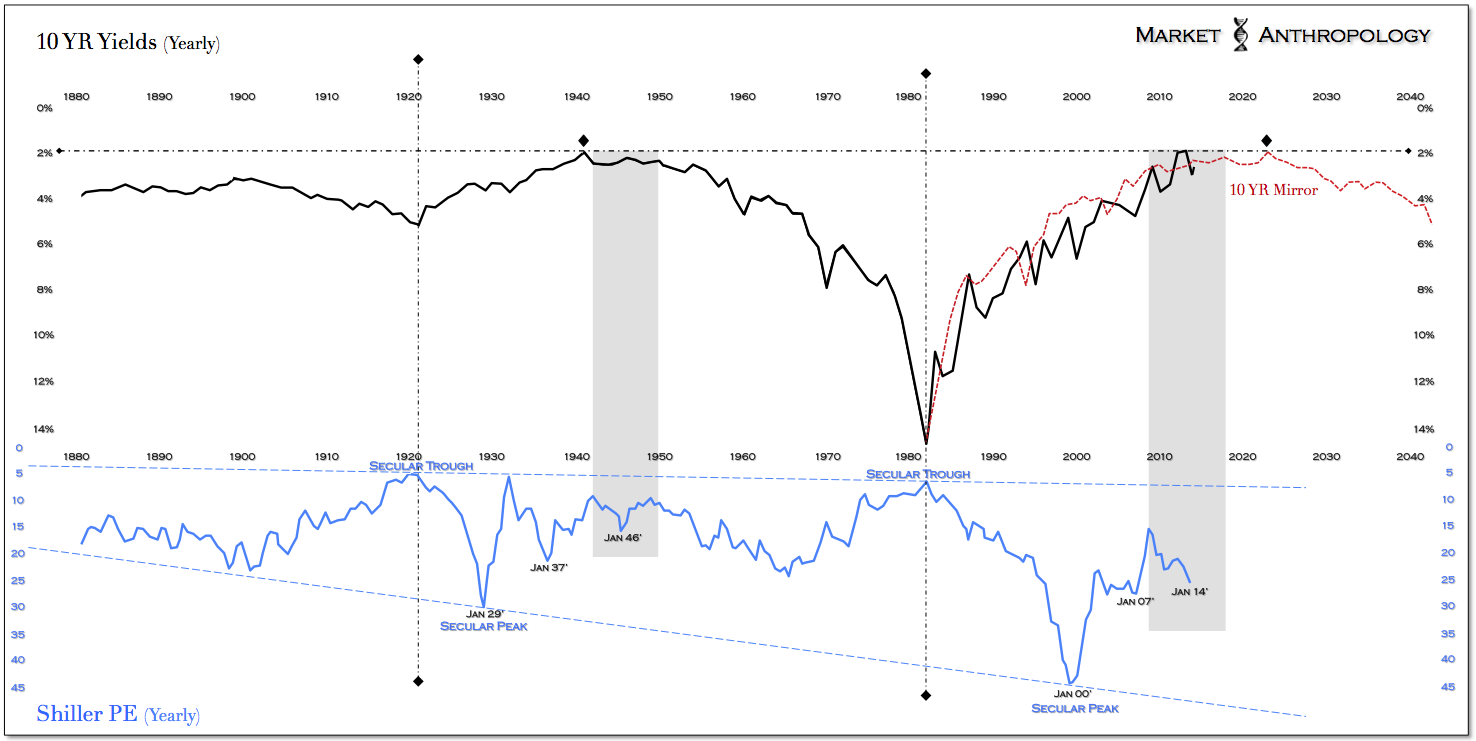

panned the one historic market environment that shares the closest parallels with the long-term yield cycle (a market the Fed has little control over) and the underlying skeptical and skittish market psychologies that defined the body politic of the market in the 1940's. Why? Ignoring the fact that it was the last time the Fed conspicuously supported the Treasury market and when long-term yields were troughing on the mirror of the cycle, it falls across the narrow window of WWII and the signing of the Treasury-Fed accord of 1951. A period apparently too dissimilar for economists who have collectively been taught to build their reference coordinates of peacetime market stability from periods after the Bretton Woods system was scuttled by Nixon in 1971. Moreover, it was a period where the Fed did not raise rates as market expectations gradually normalized from a time period defined by repeated Fed and Treasury interventions.

Over the past several months we have drawn parallels to both the equity and Treasury markets of the 1940's (see Here and Here) and believe the current market environment rhymes much closer with this time period than the more recent Fed tightening regimes we see referenced daily. On one hand, we are reminded that this isn't the 70's, where long-term yields rose rapidly with inflation expectations - and this isn't the pre-ZIRP periods of the 80's, 90's or even this centuries first decade which enjoyed a fed funds rate that could maneuver on both sides of the road. No, this is a place we have playfully referred to as Esoterica -- an unfamiliar territory for several participant generations that we have found the closest parallels with the troughing long-term yield environment of the mid 1940's.

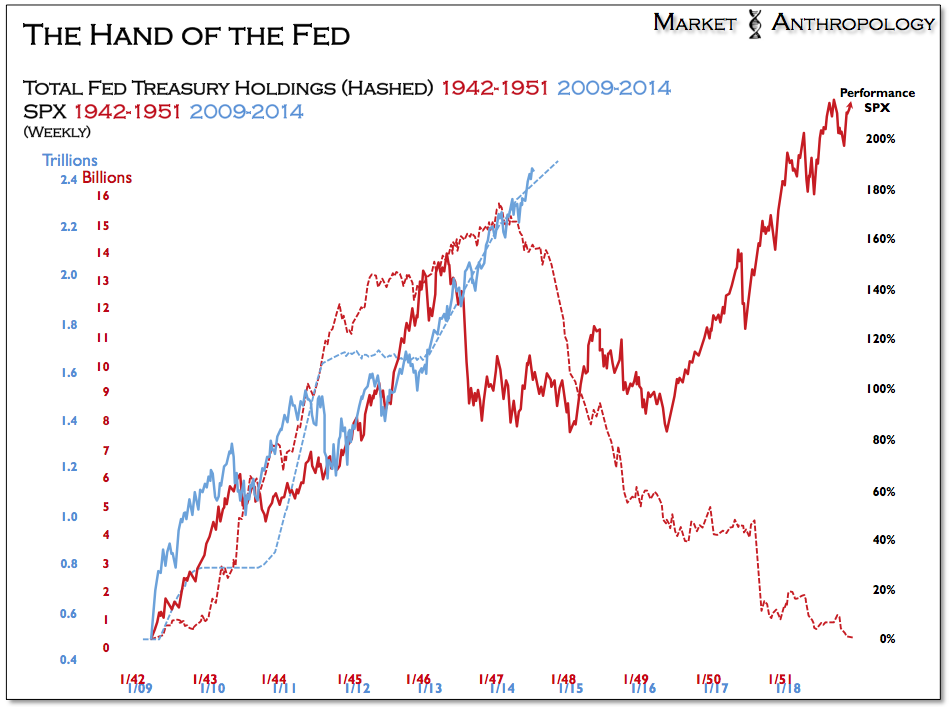

Another major parallel, which dovetails into our third point is the fact that the only other period in which the Fed actively intervened and bought the Treasury market in support of the broader system was in the 1940's. Similar with the current lackluster fundamental backdrop that has diverged over recent years from the stoic strength of the equity markets, the massive bond buying program in the 1940's had a much stronger correlation to the capital markets it directly affected than the macro climate that most economists appraise.

In an effort to keep interest rates low during and directly following WWII and avoid another chapter of the near-view Great Depression, the Fed purchased all available short-term US Treasuries and virtually all long-term US Treasuries from the market starting in April of 1942. When all was said and done, the US had a debt to GDP ratio that was almost 20% larger than where it currently resides today.

In Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz's A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960, the market climate in the 40's is described as being so sensitive and suspect of the Fed and Treasury's very visible hand, that the entire equity market rally (150+%) from the April 1942 low through the cyclical high in 1946 was viewed with great skepticism and likely to end with another pronounced economic contraction. The fresh scars of the Great Depression provided abundant fear for market participants of a possible revival of kindred economic instabilities, despite the countervailing strength of the equity markets that continued to rally more than 20% even through the recession in 1945.

What happened in 1946 when the Fed and Treasury stepped away from their extraordinary support of the Treasury markets? Similar to the air pockets experienced with the Fed pauses in QE I and QE II, the equity markets swiftly revalued expectations. From our perspective a similar fate awaits the current equity market rally, which in turn should continue to support the Treasury market -- despite rising inflation expectations and the calls by many that the Fed will begin raising rates as early as next year.

#3 - Bubble Bubble Toils And Troubles

The paradoxical market conditions that we describe in which the long-term Treasury market continues to be bid while inflation expectations strengthen, can be traced directly to swell of skepticism imparted by participants over the last two decades. Across this tumultuous period where the Fed has taken such an active role in intervening in the markets in times of crisis following periods of exuberance, investors have stepped further out on a cynical continuum of distrusting the underlying conditions that a previous generation of participants had utilized to navigate the markets. To a great degree the most successful investors of this generation have been the greatest game theorists willing to ignore the economic backdrop for the sake of the hand at play. That hand, both metaphorically and literally -- has been the Fed. When they step away this fall, the next hand played in the markets will derive motivation from this underlying skepticism, that despite the current ebullient character of the equity markets - we believe is right below the surface.

In the mid to late 1940's when inflation started strongly pulsing through the system, Treasury investors largely ignored the data for the sake of the safe haven shores of the Treasury market. Friedman described this dynamic between inflation and bond and equity yields in the following excepts from A Monetary History of the United States. ...That factor was a continued fear of a major contraction and a continued belief that prices were destined to fall. A rise in prices can have diametrically opposite effects on desired money balances depending on its effect on expectations. If it is interpreted as the harbinger of further rises, it raise the anticipated cost of holding money and leads people to desire lower balances relative to income than they otherwise would. In our view, that was the effect of prices rises in 1950 and again in 1955 to 1957. On the other hand, if a rise in prices is interpreted as a temporary rise due to be reversed, as a harbinger of a likely subsequent decline, it lowers the anticipated cost of holding money and leads people to desire higher balances relative to income than they otherwise would. In our view, that was the effect of the price rises in 1946 to 1948. An important piece of evidence in support of this view is the harbinger of yields on common stocks by comparison with bond yields. A shift in widely-held expectations toward a belief that prices are destined to rise more rapidly will tend to produce a jail in stock yields relative to bond yields because of the hedge which stocks provide agains inflation. That was precisely what happened from 1950 to 1951 and again from 1955 to 1957. A shift in widely-held expectations toward a belief that prices are destined to fall instead of rise or to fall more sharply will tend to have the opposite effect - which is precisely what happened from 1946 to 1948. Despite the extent to which the public and government officials were exercised about inflation, the public acted from 1946 to 1948 as if it expected deflation...

Although a contraction in the US equity markets has so far failed to materialize, we do expect one to gain traction as the Fed steps further away from their extraordinary measures this fall. Similar to expectations in the mid to late 1940's, we anticipate that investors will continue to support the Treasury market even in the face of inflation -- as the broader underlying skepticism of their collective anxieties will finally be realized when equity market conditions pivot lower without extraneous assistance. A self-fulling prophesy indeed -- and one that we expect will lead the current bubble prognosticators to extend themselves another link of rope, just as market expectations normalize in the wake of extraordinary support. In the meantime, we continue to like long-term Treasuries and the commodity markets relative to equities - headlined by the precious metals sector that should receive a disproportionate bidding as inflation seeps and the equity markets stumble.