Bond yields are sending an economic warning as this past week 10-year Treasury yields dropped back to 1.3%. With the simultaneous surge in the dollar, there is rising evidence the economic “reflation” trade is geting unwound.

Such is despite overly exuberant expectations of strong economic growth by the mainstream media. As we suggested in 2019, bonds generally have the outlook correct more often than stocks.

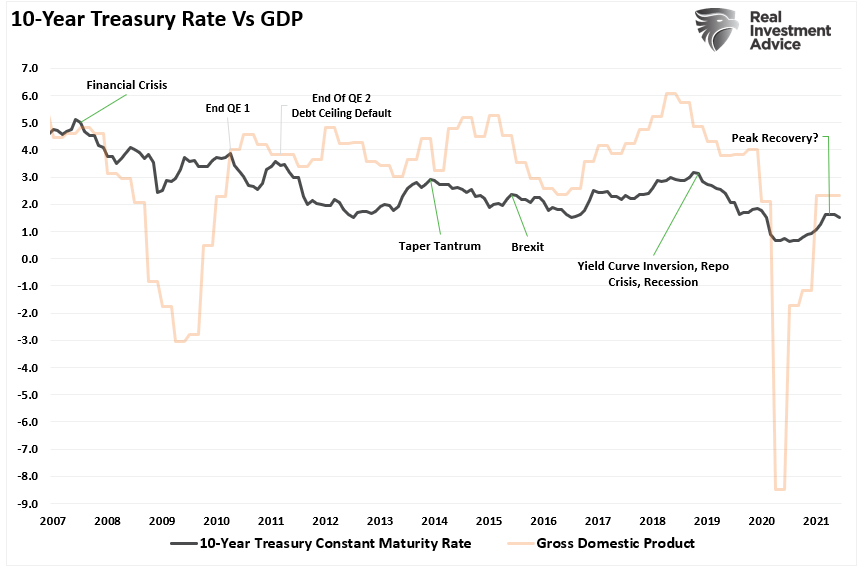

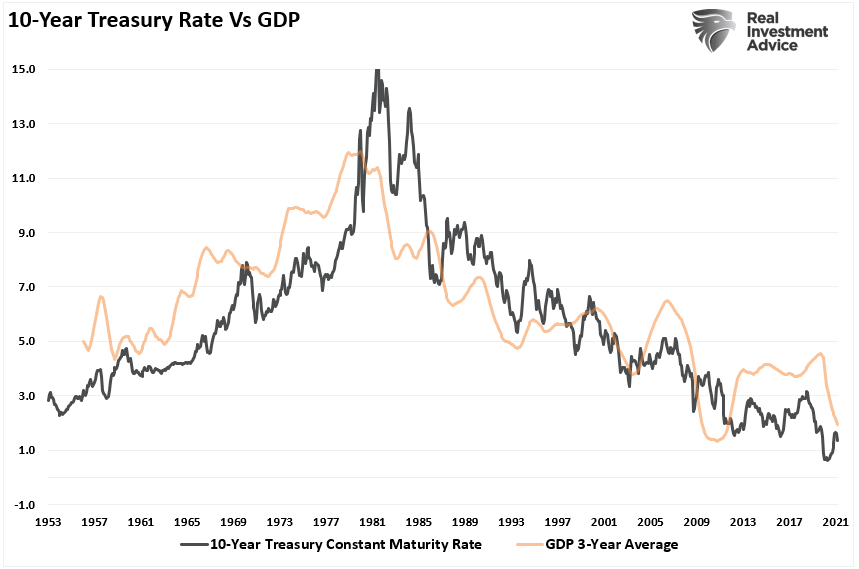

Such is not surprising as the long-term correlation between economic growth and rates remains high.

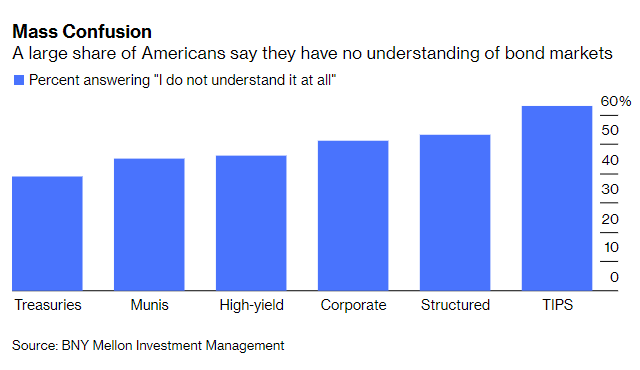

We remain in the camp that, due to the rising debt and deficits, rates must remain low. However, given most people don’t understand bonds, we will recap our previous analysis.

If you don’t understand what bonds are and what they can do for your portfolio, you may be missing out on something really big. And not just if you’re a retiree either.

Why Bonds Correlate To Economic Growth & Inflation

As stated in “bonds are not overvalued:”

“Unlike stocks, bonds have a finite value. At maturity, the principal gets returned to the “lender” along with the final interest payment. Therefore, bond buyers are very aware of the price they pay today for the return they will get tomorrow. As opposed to an equity buyer taking on ‘investment risk,’ a bond buyer is ‘loaning’ money to another entity for a specific period. Therefore, the ‘interest rate’ takes into account several substantial ‘risks:’

- Default risk

- Rate risk

- Inflation risk

- Opportunity risk

- Economic growth risk

Since the future return of any bond, on the date of purchase, is calculable to the 1/100th of a cent, a bond buyer will not pay a price that yields a negative return in the future. (This assumes a holding period until maturity. One might purchase a negative yield on a trading basis if expectations are benchmark rates will decline further.)

As noted, since bonds are loans to borrowers, the interest rate of a bond is tied to the prevailing rate environment at the time of issuance. (For this discussion, we are using the 10-year Treasury rate often referred to as the ‘risk-free’ rate.)”

There are some caveats to this analysis related to the secondary market, which we cover in the linked article.

However, the critical point is that bond buyers compensate for both what the market will pay in terms of interest rates, but also ensure they get paid for the various risks they take.

Yields Vs. Economic Growth

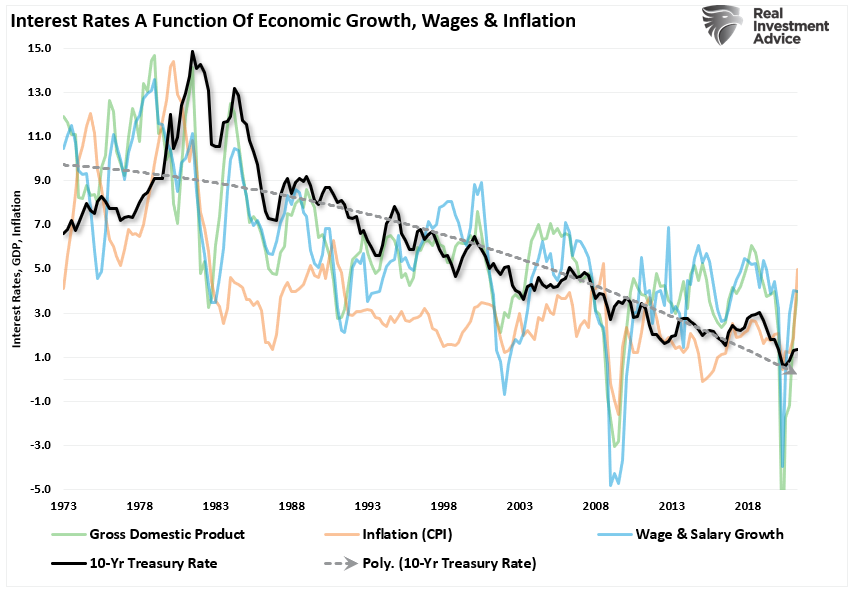

Given that analysis, it should not be surprising that interest rates reflect three primary economic factors: economic growth, wage growth, and inflation. But, again, the relationship is not unexpected as the “rate” for lending money must account for varoius risks.

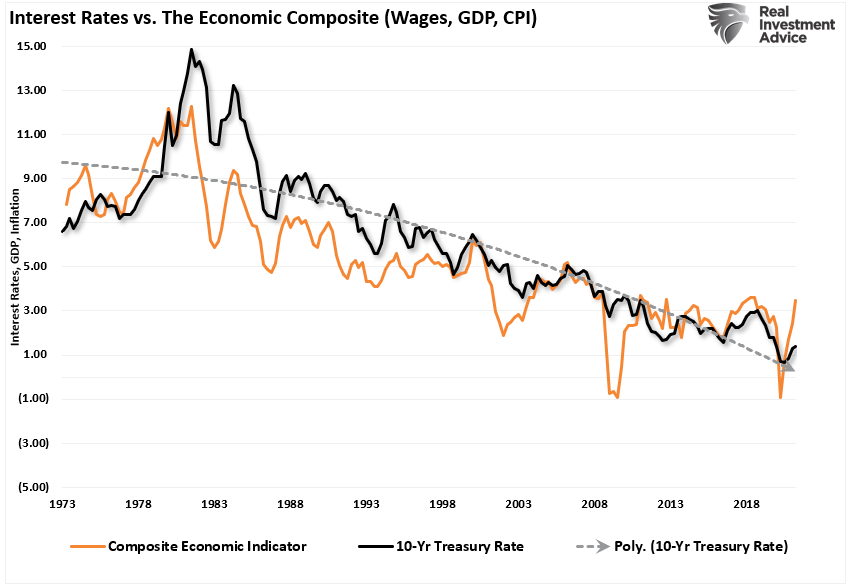

We created a composite of the three underlying measures to get a more direct relationship. For example, the chart below combines inflation, wages, and economic growth into a single composite and compares it to the 10-year Treasury rate.

Again, the correlation should not be surprising given rates must adjust for future impacts on capital.

- Equity investors expect that as economic growth and inflationary pressures increase, the value of their invested capital will increase to compensate for higher costs.

- Bond investors have a fixed rate of return. Therefore, the fixed return rate is tied to forward expectations. Otherwise, capital is damaged due to inflation and lost opportunity costs.

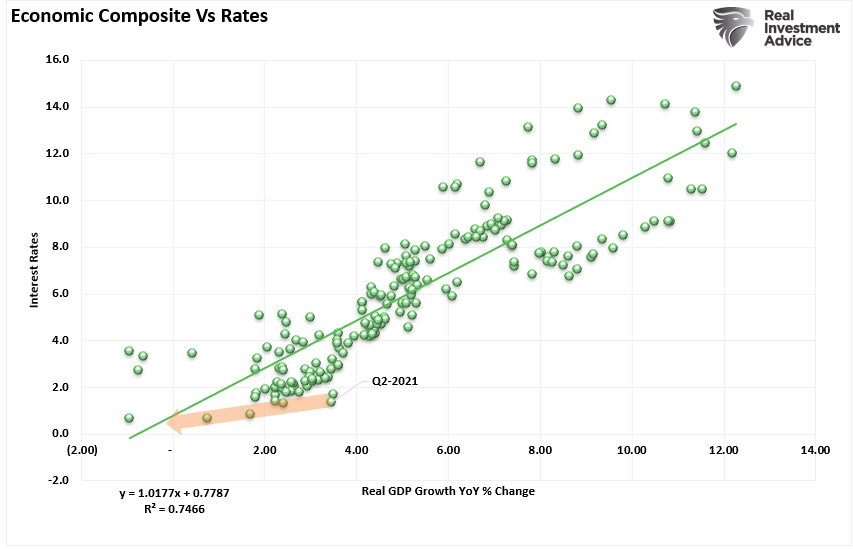

As shown, the correlation between rates and the economic composite suggests that current expectations of sustained economic expansion and rising inflation are overly optimistic. At current rates, economic growth will likely very quickly return to sub-2% growth by 2022.

The disappointment of economic growth is also a function of the surging debt and deficit levels discussed previously.

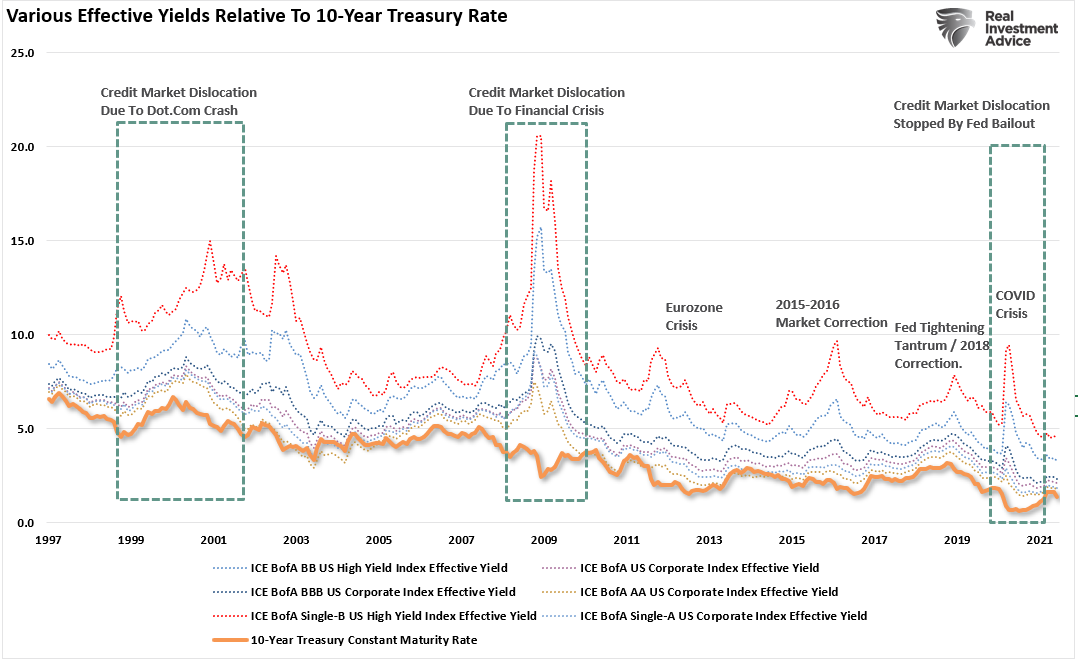

Bonds Are Sending A Warning

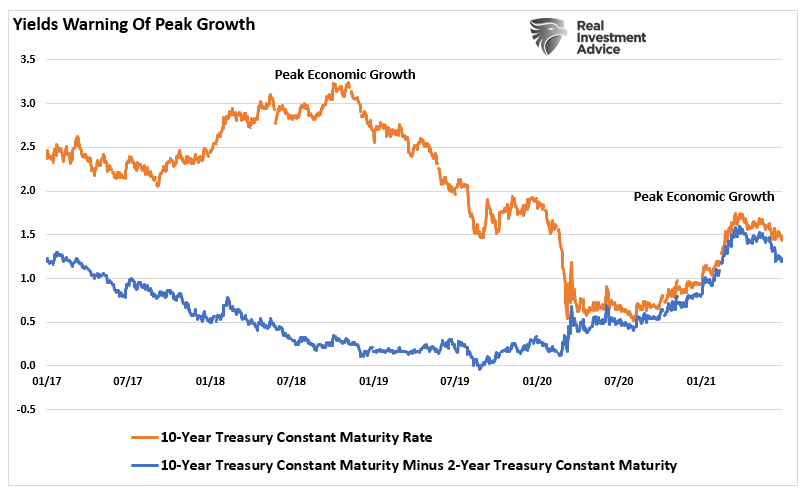

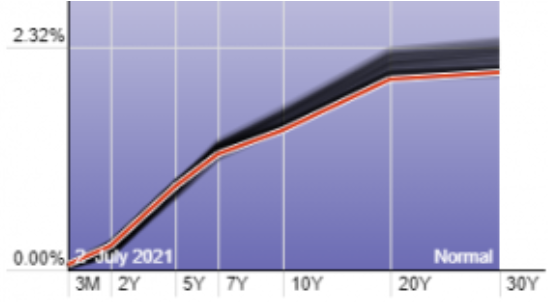

The differential between yields also confirm our concerns that expectations for economic growth and inflation are overly optimistic. The yield curve continues to flatten over the last few months as opposed to steepening with strong economic expectations.

Importantly, a flattening yield curve only suggests growth and inflation will be weaker than expected. However, an inverted yield curve is what will predict the next bear market and recession.)

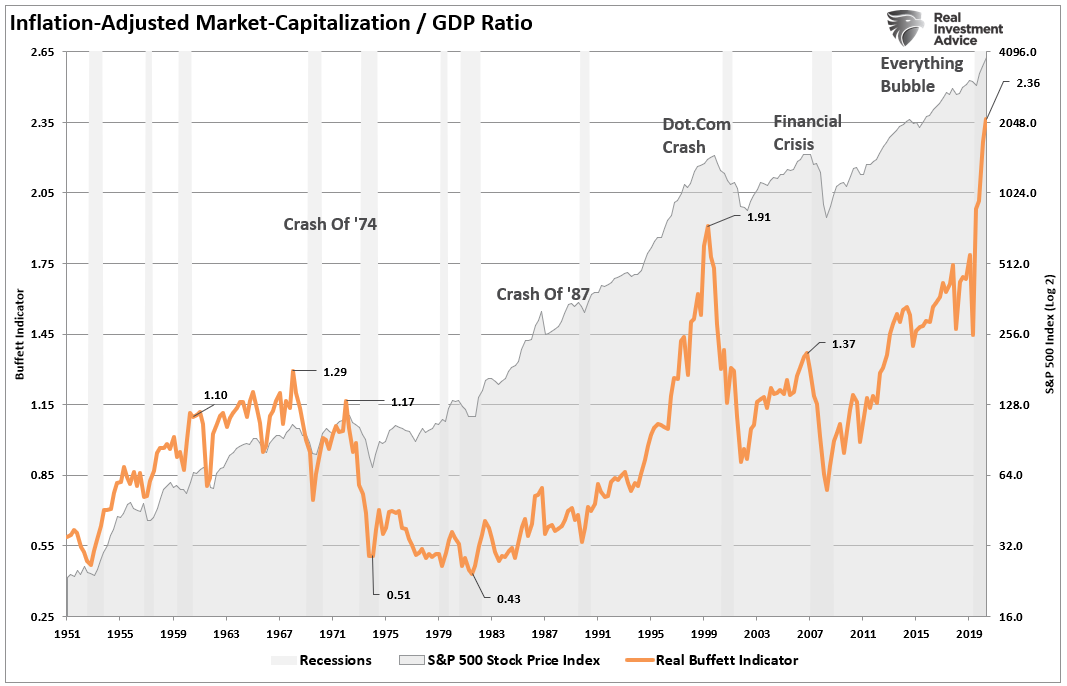

If yields are correct, then investors should be heeding its warning as lower yields will translate into slower earnings growth. In “Warning Signs,” we discussed the more extreme detachment of stocks from the underlying economy.

“The market is currently trading more than twice what the economy can generate in revenue growth for companies. (There is a long-term correlation between the rate of economic growth and earnings.)”

Investors currently “hope” that earnings will catch up with the price of the market. Such would reduce the valuation problem. However, while such is certainly possible, it has never previously happened in history.

Yields are suggesting this time will not be different.

Why We Own Bonds

As we often discuss in our weekly newsletter, we continue to opportunistic bond buyers to hedge against risk.

There is little doubt the market is currently in “risk-on” mode as investors throw “caution to wind” due to the Fed’s ongoing interventions. But, for now, that “psychology” works well.

However, when that psychology changes, for whatever reason, the rotation from “risk-on” to “risk-off” will find Treasury bonds as a “store of safety.” Historically, such is always the case during crisis events in markets.

For most investors, it was a mistake to discount the advantage of owning bonds over the last 20 years. By reducing volatility and drawdowns, investors could withstand the storms that wiped out large chunks of capital.

With stocks again grossly overvalued, a significant drawdown is probable in the coming years.

Over the next decade, the prospect of low stock market returns, possibly approaching zero, seems much less appealing than the positive return offered by a risk-free asset.

Given that we are in the most extended bull market cycle in history, combined with high valuations and weakening fundamentals, it might be time to pay more attention to what bonds can offer you.

Bonds are sending a warning once again.

Disregarding the warning has historically been costly.