Asset pricing is often mysterious as a source of figuring out exactly what Mr. Market is discounting, but in the case of bonds these days there’s no ambiguity about the crowd’s outlook. Recession is effectively a forgone conclusion, the yield curve is predicting. But while the real economy has slowed, growth remains strong enough to dispute the market’s forecast, at least for now. The question is when or if the hard data will align with market’s dark expectations?

Let’s start with Treasury yields. The widely followed 10-year/3-month spread has been consistently negative since late-May (except for one day) via daily data. This gap fell to -0.35 basis points on Monday (Aug. 12), marking the lowest print in more than a decade. Using history as a guide, this persistently inverted curve predicts that a US economic contraction is near.

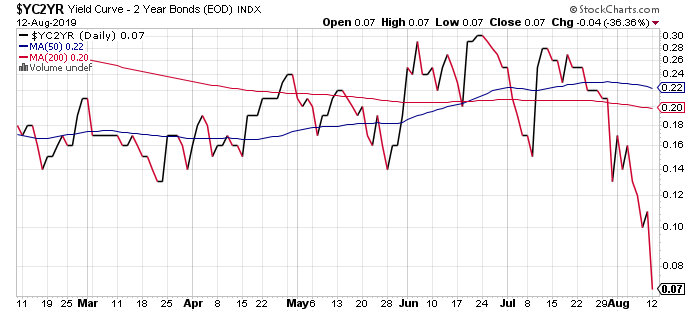

A counterpoint has been the still-positive spread for the 10-year/2-year pairing. As discussed recently, a stronger recession signal arrives when the 10-year/2-year and 10-year/3-month spreads are inverted at the same time and for the moment there’s a divergence. The 10-year/2-year gap is still positive, but just barely. This spread fell to just 7 basis points yesterday, suggesting that an inverted curve is near on this front too. At that point, if it occurs, the recession forecast will strengthen.

The Treasury market’s pricing reflects the “idea that the Fed is making a mistake,” says Andrew Brenner, head of international fixed income at National Alliance. “There’s more fear that the Fed is going to be slow in making moves, and the economy is going to go into recession.”

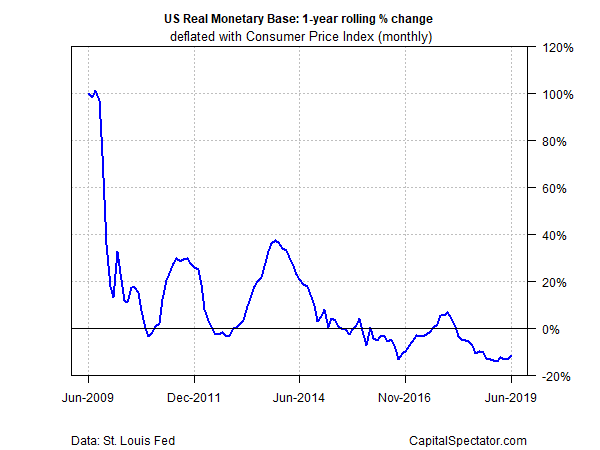

Support for Brenner’s view includes the hawkish bias that continues to prevail for the M0 money supply trend. The real (inflation-adjusted) one-year changes for this measure of base money (a.k.a. high-powered money) remain negative, extending a run to the downside that’s prevailed for a year-and-a-half. A policy bias of tightening may have been appropriate while the economy was expanding at a solid pace, but the recent slowdown suggests that the Fed’s current stance is overly hawkish for prevailing conditions.

No wonder, then, that the crowd is expecting more cuts in interest rates. Fed funds futures are currently estimating a near certainty that the central bank will trim rates again at the Sep. 18 FOMC meeting, according to CME.

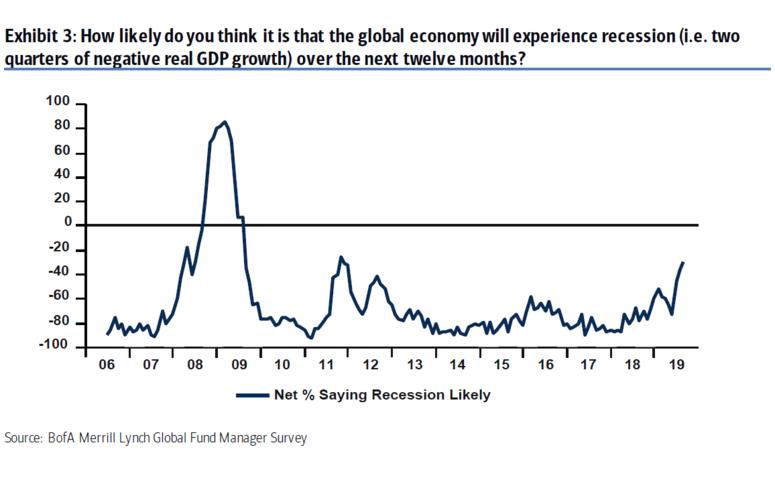

A key part of the bond market’s increasing penchant for discounting a US recession is the growing sense that headwinds are building for the global economy. Bloomberg reports that a new poll from Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) finds that roughly a third of asset managers expect a global recession within the next 12 months – the highest probability in eight years. The leading factor in the dark outlook: fears that trade-war blowback will take a toll on growth

What can an optimist say? Possibilities include the potential for clear thinking to prevail in Washington and Beijing. Taking the trade war battle down a few notches could do wonders for sentiment. That may be a long shot, but if economic and market conditions continue to deteriorate, it’s not unreasonable to assume that the US and China will soften the rhetoric and find face-saving ways to climb down the escalation latter, if only slightly.

Meantime, some analysts insist that the current state of monetary policy is only partly reflecting slower economic growth. Low rates and inverted curves are, to some extent, a byproduct of extraordinary policy decisions over the past decade and so the signals aren’t as reliable relative to the pre-2008-2009 recession.

Note, too, that the hard numbers for the US economy still reflect modest growth. That could reflect the fact that forward-looking market forecasts (yield curves, survey data and other metrics) often lead the economic reports, such as payrolls and consumer spending. When and if the two sides of this macro coin align, the die will be cast, issuing a high probability that a contraction will start. But we’re not there yet.

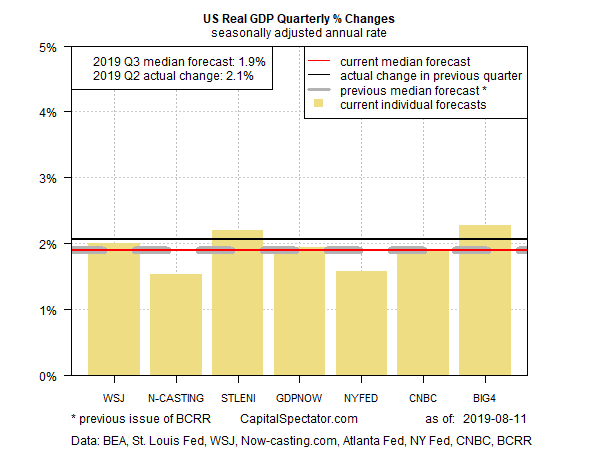

In sum, there’s still room for debate. A broad measure of the US macro trend remains modestly positive. The current nowcast for US third-quarter GDP growth is +1.9%, based on several sources. That’s a slow-bordering-on-sluggish pace, but it’s only fractionally under Q2’s modest +2.1%.

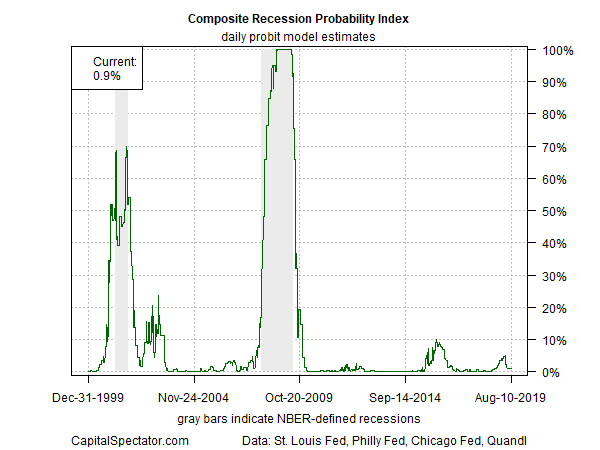

Modeling several business-cycle indexes, including the Philly Fed’s ADS Index and the Chicago Fed National Activity Index (along with proprietary metrics designed by The Capital Spectator) still reflects a low probability (1%) that a recession has already started (as shown in the Composite Recession Probability Index below).

Meantime, the near-term estimates for the US economic trend through September continue to show that a new NBER-defined recession isn’t likely. Beyond next month, on the other hand, is anyone’s guess.

That leaves us with the usual routine: watch the incoming data for new reasons to adjust the outlook (or not). The next set of key releases arrives this Thursday and Friday (Aug. 15 and 16), when we’ll see new numbers on retail sales, industrial production and housing starts for July. Using the implied one-year-change estimates as a guide (based on consensus point forecasts for monthly data via Econoday.com), the crowd’s still expecting a modest growth trend on all three fronts. Note, however, that only housing’s trend is projected to tick up in year-over-year terms. So far, so good. But given the subdued macro profile of late, combined with heightened uncertainty regarding the US-China trade war, hefty downside surprises would severely rattle the remaining optimism for the US economic outlook.

Until further notice, it seems the US-recession estimates are subject to day-to-day evaluation. For now, however, there’s still a growth bias, albeit an increasingly challenged one.