As foreign currencies weaken, non-US institutions are also in a bind for $65 trillion in FX debt.

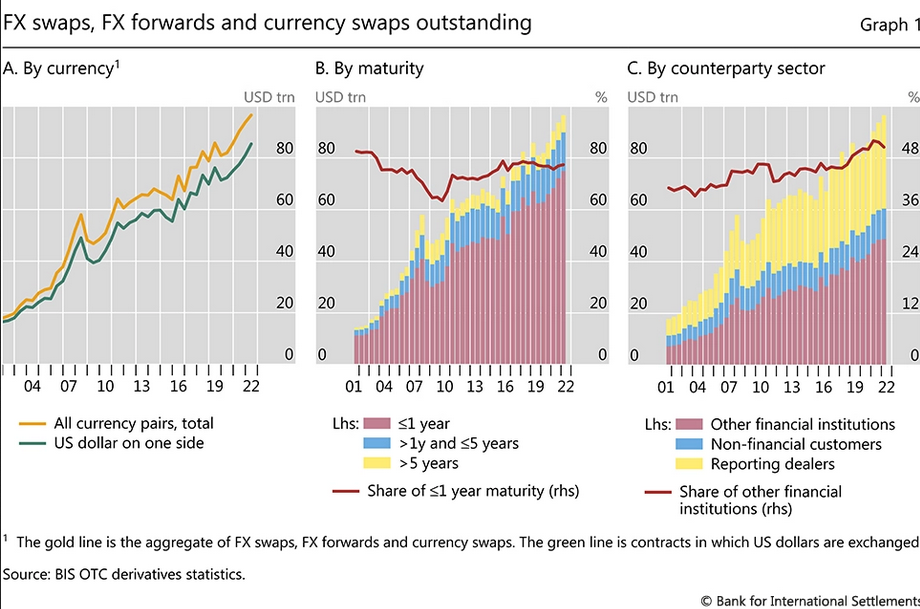

In its quarterly review, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) sounded an alarm for a massive international debt vulnerability. This global obligation rose to over $80 trillion in foreign exchange (FX) swaps, which has been reported off-balance.

From Where Does the $80 Trillion Number Come From?

Foreign exchange (FX) markets are the bedrock for international finance, allowing market participants to sell, buy and speculate on the value of national currencies. When a company buys goods and services from another country, it needs to pay for them in that nation's currency.

The FX market converts domestic currency into foreign one to facilitate such payments. Likewise, FX markets provide vital information on the relative strength of different currencies because their price reflects their supply and demand. Given their importance in international trade, FX markets are the largest and most liquid financial markets, accounting for $6.6 trillion daily trading volume.

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the US dollar is the currency used in ~87% of all foreign exchange (FX) transactions, making it the global reserve currency. In Monday’s released BIS quarterly review, the bank accounted for $80 trillion worth of FX obligations in the form of swaps and derivatives:

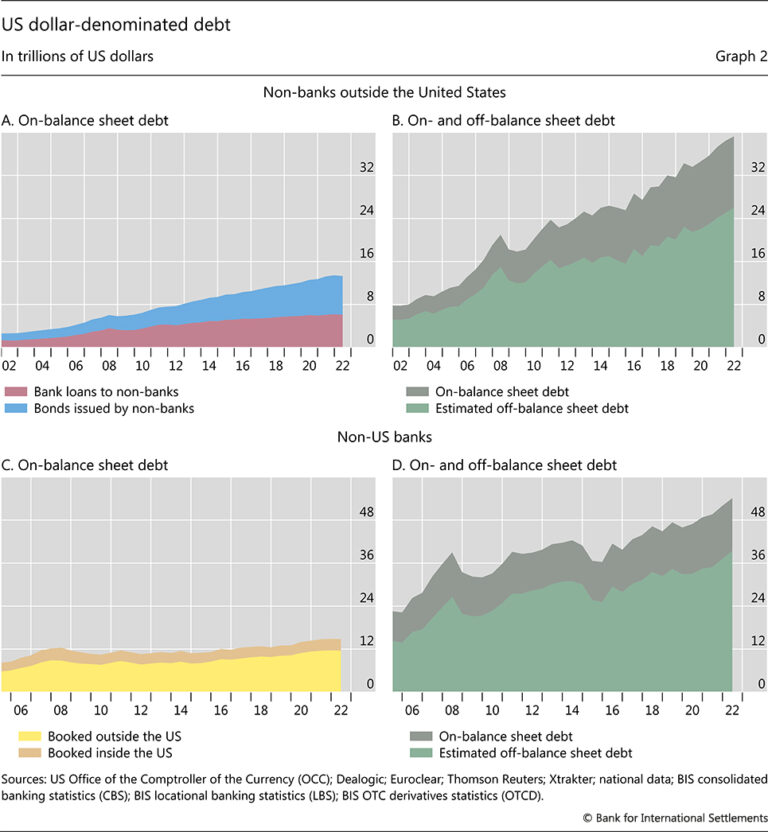

- $26 trillion among non-banks, such as pension funds, outside the US.

- $39 trillion among non-US banks with limited access to Federal Reserve credit.

- $15 trillion as on-balance sheet dollar debt.

Essentially, non-US financial institutions owe $65 trillion in dollar-denominated debt in FX swaps/currency swaps and forwards. This sum is greater than the value of dollar Treasury bills (short-term government debt), repo (repurchase agreement borrowing for short-term liquidity), and commercial paper (short-term corporate debt) combined.

Why Hasn’t $80 Trillion Been Reported Previously?

Foreign exchange (FX) obligations are typically reported on off-balance sheets. That’s because they are considered contingent liabilities. Meaning, a potential liability that may arise in the future depending on certain conditions being met. Given that this makes reporting of exact values difficult, such liabilities are reported on the off-balance sheet.

Furthermore, such reporting allows entities to report potential liabilities without affecting their reported financial position. Case in point, if a company has a significant FX exposure and the value of the currency it is exposed to drops, its reported financial position would not be affected due to off-balance sheet reporting.

However, the $80 trillion FX debt obligation has been occluded further due to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

When Did FX Debt Start to Accumulate?

The foreign exchange markets are inherently obfuscated in terms of unseen dollar borrowing. For example, if a pension fund were to borrow one foreign currency (USD) to lend another (EUR), it would later repay the USD to receive EUR. Effectively, this FX swap would act like a repurchase agreement (repo) where the currency is the collateral instead of a security.

This creates a financial system vulnerable to funding shortfalls. Following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, central banks went to great lengths to enable central bank swap lines of dollars to offshore non-US banks to preserve international financial stability.

Typically, central bank swap lines allow for one central bank to provide another central bank with foreign currency in exchange for its own currency. By doing this outside the open market, they stabilize the financial markets. This practice changed in 2008 with the dollar funneling to offshore non-US banks.

By going to offshore non-US institutions, the standard debt statistics failed to report it. This also made it difficult for monetary policymakers to account for dollar rollover needs. That is, how much has to be spent on replacing an existing debt obligation with a new debt obligation.

Considering the volatility of national currencies this year, such as EUR, GBP, and JPY, and enormous government debts, what are the implications of the revealed $80 trillion dollar FX debt?

Implications of the $80 Trillion FX Obligations

Weighted against the EUR, GBP, and JPY, we have seen the dollar strength index (DXY) rise to a 20-year high this year, reaching its peak in September at 114. That’s because the Federal Reserve engaged in the fastest rate hiking cycle since the early 1980s to combat an equally historical inflation rate.

Because ~87% of foreign exchange transactions are in dollars, this caused a global liquidity squeeze.

The dollar strength index (DXY) vs. its counterparts euro (EUR), British pound (GBP) and the Japanese yen (JPY), year-to-date. Image credit: Trading View.

One of the manifestations of the dollar squeeze was the Bank of England (BoE) buying up to £10 billion of government bonds (debt) per day to prevent UK pension funds from going under. However, in the first half of November, the demand for dollar buyers lowered, bringing DXY down to the June level.

Nonetheless, the outstanding FX debt will pressure foreign countries to print more of their own currency to swap for dollars. In turn, an increased money supply of their currencies will likely cause higher inflation rates, while the dollar will once again begin to rise.

Theoretically, the Federal Reserve could start cutting rates again to bring the dollar down. But Fed Chair Jerome Powell repeatedly said that rates will remain restrictive until the target 2% inflation rate (PCE) is reached.

It appears that Powell was correct when he said that “the economy as we know it might be over” in November 2020 at the ECB Forum on Central Banking.

In addition to having $80 trillion in FX liabilities, about 80% of their maturity date is under one year.

The combination of the Fed’s rate hikes, global inflation, and the dollar’s stranglehold on settlements makes for an exceedingly fragile global financial system. One that may lead to stagflation, a combo of high inflation and low economic growth, leading to stagnant demand and rising prices.