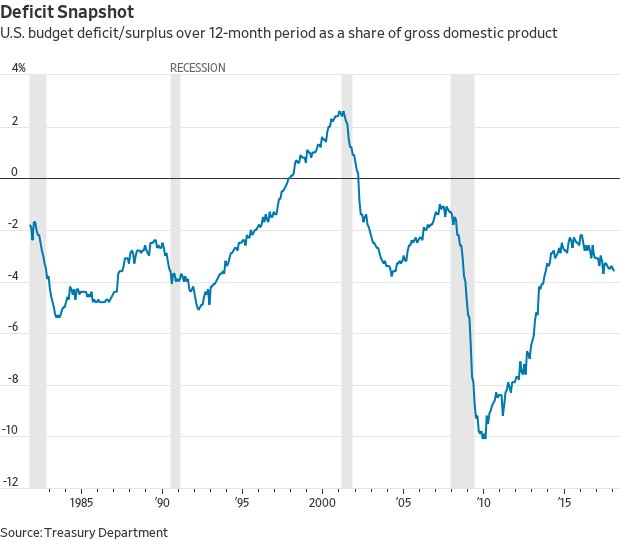

The US federal government on Monday reported its biggest budget deficit in February in six years. By some accounts, the news offers another reason for projecting that Washington’s red ink and inflationary pressures will heat up in the months and years ahead.

Some analysts warn that the tax cuts enacted last year will raise the government’s debt load in the years to come. One estimate projects that the reduction in tax rates will cut federal revenue in excess of $1 trillion over the next decade. There was a degree of support for that estimate in yesterday’s Treasury data, which reflected a 9% slide in revenue in February vs. the year-earlier month, in part because withholding taxes were 2% lower, MarketWatch reported. Meanwhile, spending linked to net interest on the public debt jumped 9%.

Nick Timiraos at The Wall Street Journal notes via Twitter that “over the 12 months ended February, (Donald Trump’s first full year in office), the federal budget deficit widened to $703 billion (3.6% of GDP), up from $583 billion (3.1% of GDP) over the prior 12-month period.”

The connection between deficits and inflation is debatable, although an economics note from the St. Louis Fed in 2004 advised:

Deficits can be a source of inflation if they are accommodated by monetary policy — that is, if the Federal Reserve responds to higher deficits by increasing the growth of money. The Federal Reserve has two ways of responding to higher deficits:

1. The central bank directly purchases the securities issued by the government to finance the deficits.

2. The private sector purchases these same securities; then, the central bank attempts to limit any potential interest rate increases.Under either scenario, deficits lead to greater money base growth, which can create inflationary pressure.

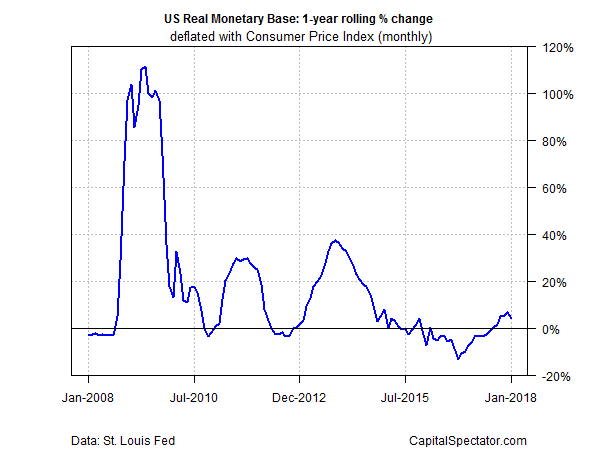

It’s interesting to note that real year-over-year growth in base money has been rising in each of the past six months through January – at a time when the central bank’s monetary policy is said to be tightening. Is this a sign that hawkish turn in policy is less hawkish than generally assumed?

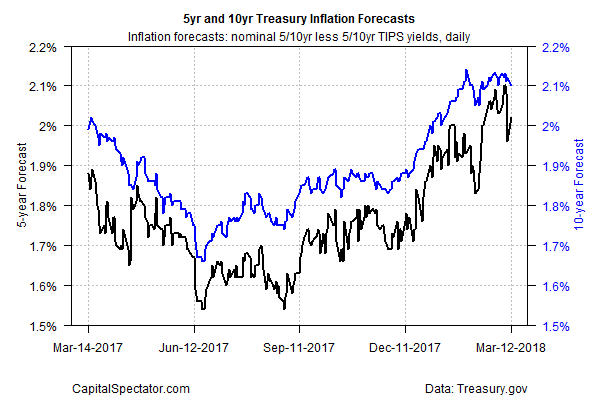

The Treasury market is certainly pricing in a higher inflation scenario lately. The yield spread on nominal less inflation-indexed 5- and 10-year Treasuries have recently increased to the highest levels in five years before pulling back from those highs in recent days.

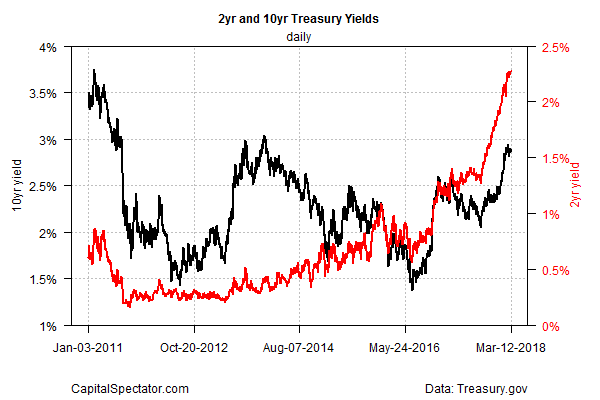

For some analysts, the writing is on the wall. “Stimulative but unpaid for tax cuts in the late stages of the business cycle have pushed up bond yields to the point where it has already started to cause stress,” says Jeff Caughron, chief operating officer at the Baker Group, which provides consulting services to community banks. “The Treasury is faced with the prospect of having to flood the market with all this supply to fund these deficits.”

Optimists remind that official inflation measures are still low by historical standards – the core consumer price index, for instance, is running slightly below the Fed’s 2% target, although today’s update for February is expected to show an uptick to 1.9%, according to Econoday.com’s consensus forecast.

Nonetheless, there’s a growing sense that the tide is turning and the inflationary trend is now trending up, albeit gently.

Today’s “core-CPI release will undoubtedly be the tone-setting event for the next several weeks in the Treasury market, or at least until the FOMC updates the dot-plot next Wednesday,” advised Ian Lyngen and Aaron Kohli, fixed-income strategists at BMO Capital Markets, in a note to clients. “An acceleration of core pricing pressures will offer confirmation that this will finally be the year for inflation to return in earnest.”