Identifying which way the macro wind is blowing isn’t getting easier. So far this month the government has published five key economic reports and each one has delivered sharply divergent results relative to the consensus forecasts.

It’s unclear how long the surprise factor will remain in overdrive, but for the near term the incoming numbers may be unusually misleading.

The hefty surprises started with the release of nonfarm payrolls for April. Economists were looking for a sharp gain of nearly 1 million jobs. The actual number was a dramatically weaker rise of just 266,000.

Subsequently released numbers for consumer inflation, retail sales, industrial production and yesterday’s housing starts also posted results that were far from the consensus point forecasts.

Yes, forecasting is almost always wrong, but the magnitude of the recent errors, one after the other, suggests that there’s a higher degree of noise in the numbers than usual.

The uncommonly big string of misses for expectations vs. results is fueling increasingly stark forecasts in some corners. For inflation, some economists advise that the sharp increase in pricing pressure will eventually normalize and so it’s a mistake to assume that the latest surge in consumer prices is a sign of things to come.

But other dismal scientists disagree, including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, who yesterday warned that the Federal Reserve is making a mistake by not pre-emptively tightening monetary policy to derail higher inflation. He predicts that the Fed will soon be forced to sharply hike rates to compensate for its “dangerous complacency” with assessing inflation risk.

There are, of course, narratives that explain the various big misses. The surprisingly big decline in housing starts in April, for instance, is blamed on surging lumber prices.

As Fannie Mae Chief Economist, Doug Duncan stated:

“This report may be the strongest evidence yet that supply constraints, namely lumber and material prices, labor scarcity, and a lack of buildable lots, are weighing meaningfully on homebuilders’ ability to keep up with housing demand.”

The good news is that the broad macro trend still looks favorable. Business cycle indicators such as the Philly Fed’s ADS Index continue to reflect a strong expansion in progress. Meanwhile, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model is estimating that the second-quarter economic growth will continue to accelerate to a sizzling 10% pace.

Nonetheless, the noise factor is unusually high and so incoming data may continue to surprise forecasters by a wide margin. In turn, the noise will make it easy to spin results in the extreme.

The source of the noise, of course, is the lingering after-effects of the pandemic, which created widespread havoc in economic models and general efforts to find reliable trending signals. Add in ambitious fiscal and monetary policies intent on correcting the imbalances and you have a fertile environment for big surprises in economic numbers.

Perhaps sometime in the second half of the year the data will begin to normalize as the more extreme results of the year-over-year comparisons wash out of the data. Meantime, the monthly numbers look set to deliver more surprises, up and down.

Looking through the noise is always an essential task in macro analysis. Unfortunately, that could be an unusually tough assignment for the foreseeable future.

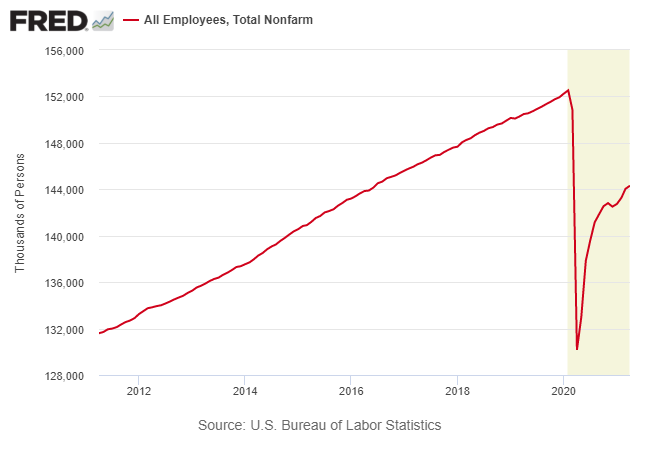

The magnitude of the challenge is in large part linked with the labor market, which is still far below its pre-pandemic level.

“The question of how to unclog the labor market is going to be a critical one,” said Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin. "If efforts to extend recovery on this front falter, economic growth could end up being weaker than expected. You have a logistical challenge of shutting down an economy and bringing it back up and we are not built for that.”