Will 2020 be better than 2019 for the yellow metal? We invite you to read our today’s article, which provides an important update of the macroeconomic outlook for 2020 we painted one month ago. Read it and learn what has changed among the fundamental factors and whether they will become less or more friendly toward gold.

In the January edition of the Gold Market Overview, we wrote that in 2020, “the macroeconomic environment could be less supportive for gold than in 2019.” Please note that we did not write that the price of gold would be lower, but that gold’s fundamentals could deteriorate in 2020. The change in fundamentals, of course, can send gold prices lower, but it can merely soften the gains, or it can even have no impact on the price of the yellow metal at all, as technical factors can outweigh the fundamental drivers. It could also be the case that gold plunges based on the technical factors while the fundamentals are only somewhat worse than they’ve been last year.

However, perhaps we should still update our gold outlook for 2020. Our thesis was based on several assumption, some of which no longer apply. In particular, we forecasted that 1) the Fed will be in a wait-and-see mode, but with a dovish bias; 2) the US fiscal policy will remain easy; 3) U.S. dollar should stay strong. Let’s reexamine them!

First, we still do not expect that the Fed will cut federal funds rate this year (unless the crisis arrives, of course). Maybe one cut is possible, but the wait-and-see mode is our baseline scenario. This is why we stated that we would see in 2020 “a more hawkish stance than in 2019 when we witnessed three interest rate cuts.” But we could underestimate the significance of the repo crisis and the Fed’s readiness to pump money into the financial system. After all, the US central bank switched quickly from quantitative tightening, i.e., withdrawing around $50 billion per month into quantitative easing, i.e., injecting $60 billion per month. It’s not easy to quantify, but it might be the case that, even without any additional interest rate cuts, the overall monetary policy will not be significantly more hawkish after all, especially that on the last day of January the yield curve has inverted again.

Second, based on the presidential projections that forecasted that the fiscal deficit would increase to $1,101 billion, but decrease as a percent of GDP, we assumed that the fiscal stance will remain similar to the last year’s. But now we have fresh data about the US fiscal policy. We know that the budget deficit surpassed $1 trillion for the 12-month calendar year ending in December. And, what is even more disturbing is that for the first quarter of fiscal year 2020, which began on October 1, the deficit grew almost 12 percent year-over-year.

Yes, you read it right. Twelve percent – in times of peace and economic expansion that brought the unemployment rate to a 50-year low. And in times of rising government’s revenues, which increased 5 percent. But the government’s outlays rose even more, 7 percent, so the $358 billion deficit occurred, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

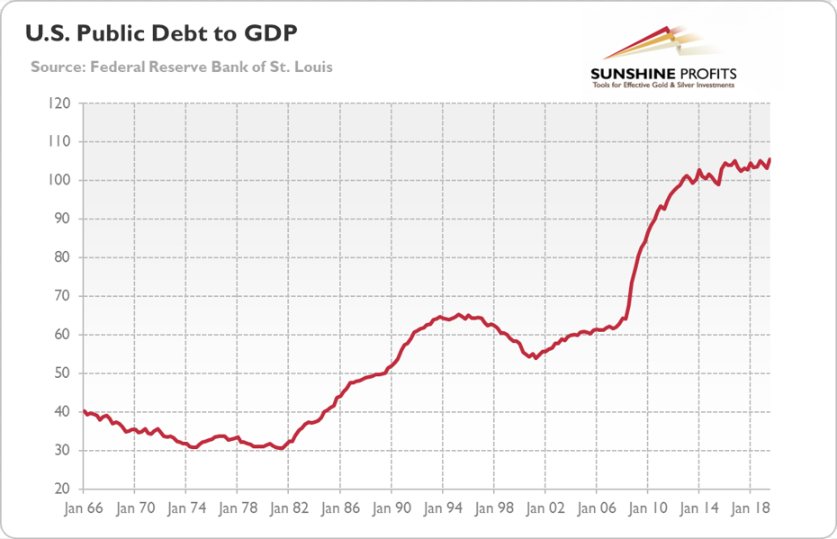

What is also eye-popping is that the total public debt stood at 105.5 percent of GDP at the end of Q3 2019, as the chart below shows, and it is likely to rise over time, as both parties would keep the spending spree going. The Congressional Budget Office’s baseline scenario is that the federal debt will increase to 144 percent by 2049, or even to 219 percent of GDP in the alternative scenario, which would be unprecedented in US history.

Chart 1: Total US public debt as a percent of GDP from Q1 1966 to Q3 2019

So, there are high chances that the fiscal stance in 2020 will be even easier than in 2019, which should support the gold prices, even though the markets seem to downplay the risk of financial crisis as far as the interest rates remain at ultra low level.

Third, we assume that as long the US economy outperforms its major peers, the greenback should remain strong. Although it makes sense and the dollar still looks relatively well, when compared to the euro or Japanese yen, we could also witness some developments that would hurt the greenback. What we mean here, is the fact that the divergence between the pace of economic growth in the emerging markets and the US is likely to widen.

According to the IMF’s estimates, in 2019, the emerging markets grew 3.7 percent, while the US – 2.3 percent. Meanwhile, in 2020, the emerging markets are expected to expand 4.4 percent, while the US only 2 percent. Traditionally, when the emerging markets accelerated significantly relatively to the US, the dollar struggled. Moreover, as risk appetite is stronger, partially thanks to the signed trade truce between the US and China and the Powell’s put, the safe-haven demand for the US dollar may weaken. So, although the softer risk aversion is negative for gold as well, the acceleration in growth of emerging markets compared to the US may take some wind off the greenback’s sails (at least relatively to the emerging market currencies) and ease the pressure on gold prices.

Hence, the macroeconomic environment in 2020 can be better for gold than we previously thought (we were not fundamentally bearish, but we presumed that the fundamentals at least suggest smaller gains than in 2019). As you can see, we are always open to new data and developments. We are not biased or married at all costs to our original views. We are always ready to update our stance as quickly as the new data justifies it. Our Readers deserve it.