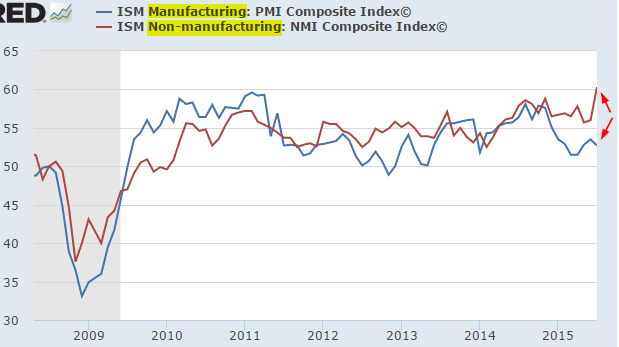

Yesterday's ISM non-manufacturing report showed US services sector expansion considerably stronger than economists had anticipated. The strength of the services sector expansion however has diverged materially from what we see in US manufacturing.

|

| Source: St. Louis Fed, ISM |

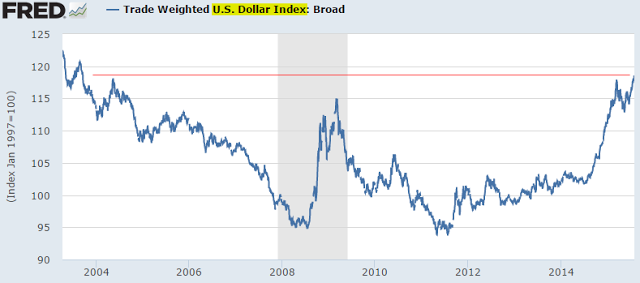

The reason for the divergence is the strength of the US dollar, which on a trade-weighted basis is at the highest level in over a decade.

|

| Source: St. Louis Fed |

The strengthening US currency has generated a significant drag on growth in the manufacturing sector. We've all read the headlines:

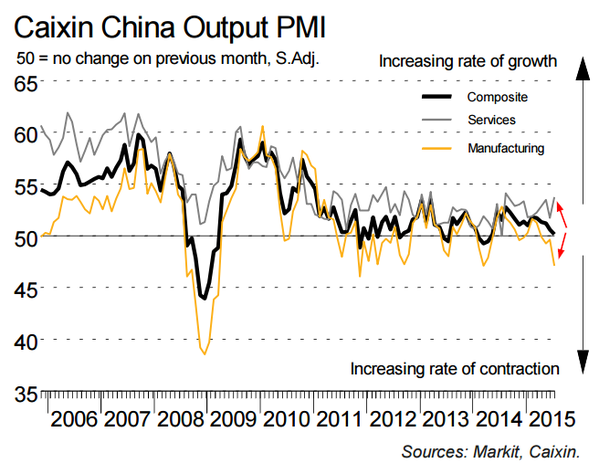

But haven't we seen this divergence between the services and the manufacturing sectors elsewhere? Indeed, on Tuesday Markit published a similar chart for China.

|

| Source: Markit |

This of course is more than a coincidence. China's currency tie to the US dollar resulted in a similar dynamic of manufacturing sector significantly underperforming. Unlike the US however, China's manufacturing is more sensitive to exports, making the slowdown far more pronounced and resulting in an outright contraction (PMI below 50 in the chart above).

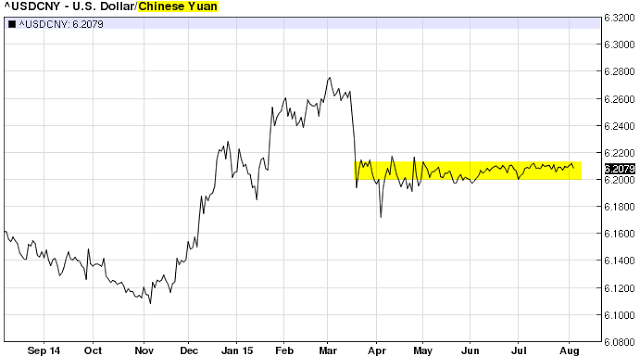

In recent months the yuan has been firmly pegged to the dollar. There are a number of reasons for this linkage, including China's wish to make the yuan part of the so-called Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), a basket of currencies constructed by the IMF and held by various central banks. Beijing reasoned that the yuan's stability would help them with that cause.

|

| Source: barchart |

However, on Tuesday we got this headline:

|

| Source: Reuters |

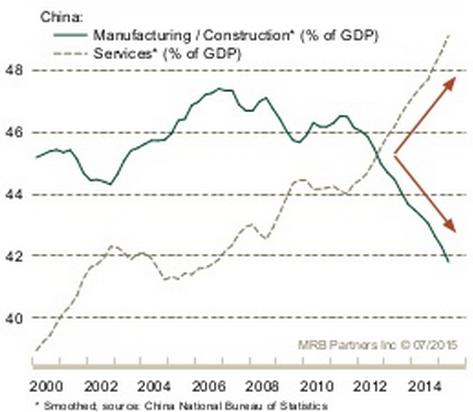

Time to give up the peg? There are of course other reasons China may want to maintain the link to the dollar - one of them is to continue "rebalancing" the economy.

|

| Source: MRB |

This policy however could prove to be too costly, as competitors whose currencies have been devalued may take market share from China. Here is how the yuan has appreciated against the Mexican peso for example (chart below). With margins tightening in a number of industries, when a manufacturer decides where to build a factory, Mexico (and a number of other countries) may now be a cheaper solution.

It's unclear if China will ultimately let the peg go or if the yuan will continue tagging along with the US dollar. Will China want to wait until the 2016 IMF decision on the SDR inclusion? With the Fed getting ready for "liftoff" in September, while most central banks are easing the dollar could continue marching higher.

This could slow China's economic growth materially below the current ("reported") 7% per year. In effect the tightening of monetary conditions in the US will be transmitted to China via the peg. If the dollar indeed moves higher as US rates rise, will Beijing finally run out of patience?