Where metal prices are going in 2014 is, admittedly, a tough prediction to make – even following respected sources such as Reuters and the Economist produces sharply differing views.

In Reuters’ opinion, or at least what’s espoused in its recent newsletter, commodities (and by this they include metals) are set to distinguish themselves from equities, against which they have tracked doggedly since the 2008/9 financial crisis, and start forging direction on their own, driven, the article suggests, by their own fundamentals.

Historically, Reuters points out, commodities and equities have tended to move independently of one another. But for most of the period since the stock market’s March 2009 trough, the performance of the Thomson Reuters/Jefferies CRB commodity index has closely tracked that of the MSCI World Index of stocks.

What is the driver for this change, you may reasonably ask?

The early moves in late 2013 have been the result of supply and demand fundamentals becoming so overwhelming they have finally begun to impact the market.

Particular note is made of copper and iron ore capacity, but next year it is the rolling back of quantitative easing that will continue the divergence of metals from equities and indeed of metals from metals, in contrast to how metals have moved in lockstep over recent years.

All in all Reuters believes this will see equities continue to rise as they benefit from falling raw material, oil, natural gas and subdued wage demands, company profits will remain robust – outside of the mining industry, if their argument is correct.

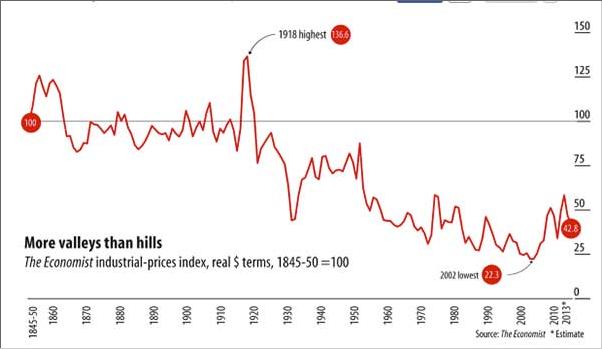

The Economist, on the other hand, is taking a contrarian position, arguing in its “The World in 2014” year-end publication that while the commodities super-cycle in terms of Chinese double-digit growth is a thing of the past, rising global growth combined with single-digit growth in China – by far the world’s largest metals consumer – will result in still-strong global demand growth for metals, and hence upward pressure on prices.

From a historical perspective, the Economist argues metals prices are relatively low and the lows of the 1990s should be seen in the context that the West had largely finished its resource-intensive growth phase – building of bridges, roads and so on – but the emerging markets, particularly China, had not yet started.

Since the first half of the last decade, though, China’s growth has been so vast that in a few short years the economy has mushroomed from insignificance (in metals terms) to becoming the world’s largest consumer. Even lower growth there will continue to underpin strong demand.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Base-Metals Battle: 2014 Price Outlook

Published 01/09/2014, 12:56 PM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Base-Metals Battle: 2014 Price Outlook

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.