Risks to the euro area's ongoing economic recovery have risen recently as Greece once again takes center stage. The nation is about to become the first developed economy to default on its IMF obligation (joining countries such as Sudan and Iraq). Such outcome may also ultimately result in its exit from the EMU.

Reuters: - Cut off from markets and refusing so far to accept the terms set by its lenders, the Greek government may have to choose in the next few weeks to pay salaries and pensions or repay International Monetary Fund loans.

Its official creditors - the euro zone and the IMF - have frozen bailout aid until the new leftist-led government in Athens reaches agreement on a comprehensive package of reforms.

A deal had been pencilled in for an April 24 meeting of euro zone finance ministers in Riga, but it now seems too ambitious, officials said.

That has raised fears the Greek government will not be able to make its next payments to the IMF, which total some $1 billion over the next month. Missing an IMF payment could mean default and, eventually, an exit from the euro zone.

The fiscal situation in Greece has become untenable, with tax revenue collapsing and government cash position barely sufficient to pay government employees and cover pension obligations through the end of the month.

Reuters: - Greece will need to tap all the remaining cash reserves across its public sector -- a total of 2 billion euros -- to pay civil service wages and pensions at the end of the month, according to finance ministry officials.

Barring a last-ditch deal with its creditors, that is likely to leave no money to repay the International Monetary Fund almost 1 billion euros due in the first half of May, although Greece has said it wants to honor its debt obligations. Athens' scramble for basic funds shows how extreme the financial constraints on Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras have become as he tries to convince skeptical foreign creditors to extend his country new financial aid.

Will we see a last minute compromise? Perhaps. But the Eurogroup is experiencing what many dealmakers would categorize as "deal fatigue" - the motivation to find an emergency solution is no longer there. Moreover, the political climate does not favor a compromise with Greece. While the focus has been on Germany, it is the smaller nations such as Slovenia that have argued vehemently that Greece must comply with the original bailout terms. Slovenia, who struggled through the downturn, cutting pay and shrinking expenditures, views Greece as using the bailout funds for pay increases - and then asking for debt forgiveness. Slovenia's taxpayers whose pensions are considerably lower than those in Greece will not look favorably upon such action.

The Slovenia Times: - Our exposure to Greece is 2.7% of GDP, which was in a year after we had a 8% fall in GDP and when we had to slash pay and economise in all areas."

This is why Slovenia will insist on Greece continuing with the restructuring and continuing to meet its obligations to Slovenia as well as international institutions, [Slovenia's Finance Minister Dušan] Mramor said.

"Given such an exposure Slovenia has toward Greece and such solidarity we provided, Greece has said it plans to raise pensions, raise pay, make employments in the public sector and demand an extra cut it its liabilities to Slovenia, while in Slovenia we are slashing pay and economising in all areas," Mramor said.

With little political will to provide additional financing, what happens after the IMF default by Greece? According to Bank of America (NYSE:BAC), "it would trigger a parallel default to the Eurozone bail-out fund (EFSF) under the legal master agreement, and might force the EFSF to cancel its loan packages and demand immediate repayment. This in turn would trigger a default on Greek government bonds issued under the bail-out accord."

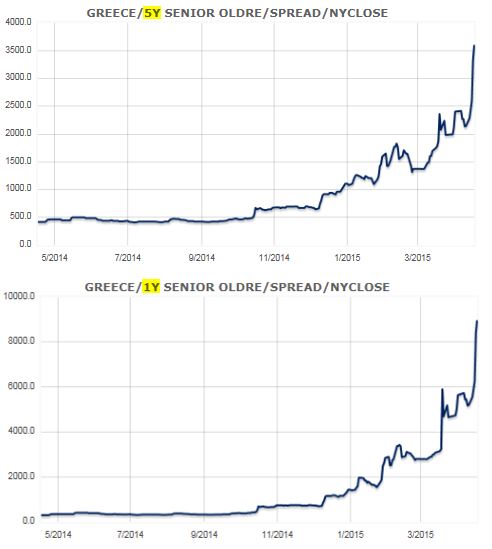

The markets are pricing the probability of default as a near certainty at this point, with credit default swap spreads blowing out.

|

| Greece 5-Year and 1-yr sovereign CDS spreads (source: Barclays (LONDON:BARC) Research) |

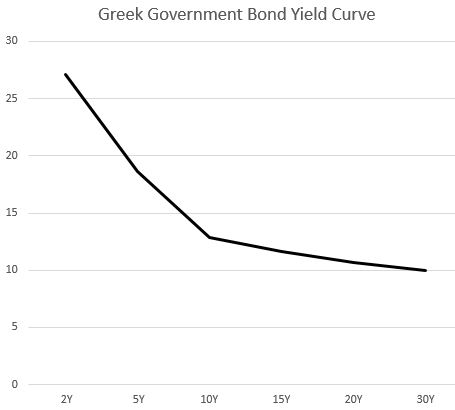

The Greek sovereign debt yield curve has inverted further, with the Greece 2-Year yield now above 25%.

It is not at all clear what will happen after the default, but the so-called Grexit becomes increasingly likely. Most analysts now believe that unlike in 2012 the Eurozone will be able to weather this storm due to its better capitalized banks, the ongoing quantitative easing by the ECB (coupled with other measures such as TLTRO), well established bailout mechanism (the ESM), and the OMT backstop facility designed to allow the ECB to support any state that is having liquidity problems. The Eurozone should be able to absorb the losses on some €330bn government exposure to Greek public debt.

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin (via Reuters): - "We have learned to build walls to protect ourselves, to protect the banking system, to protect other countries which could become fragile, if something happens in Greece. So Europe is much stronger. Europe has sheltered itself from turbulence. The danger is for Greece."

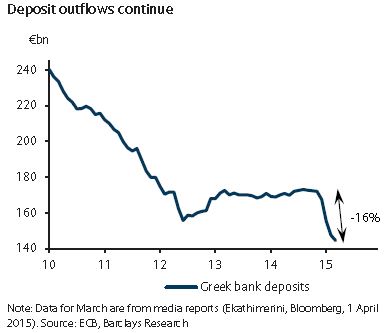

However, as discussed before, the nation's divorce from the European Monetary Union will be complex and fraught with more uncertainty than many realize. It's not just about Greece defaulting on on the public debt but also about extracting the Bank of Greece from the Eurosystem. By the time Greece imposes capital controls - which seems increasingly likely - the run on Greek banks will have taken its toll. Deposits have already declined sharply since late last year.

|

| Source: Barclays Research |

The Greek banks are replacing these lost deposits with emergency funds (ELA) from the Bank of Greece, who is in turn borrowing from the Eurosystem via TARGET2. With these banks increasingly dependent on central bank support, valuations are collapsing as the need for more bailouts becomes clear. This is especially the case if Greece defaults on its bonds which are widely held by Greek banks.

|

| Greek banks share index |

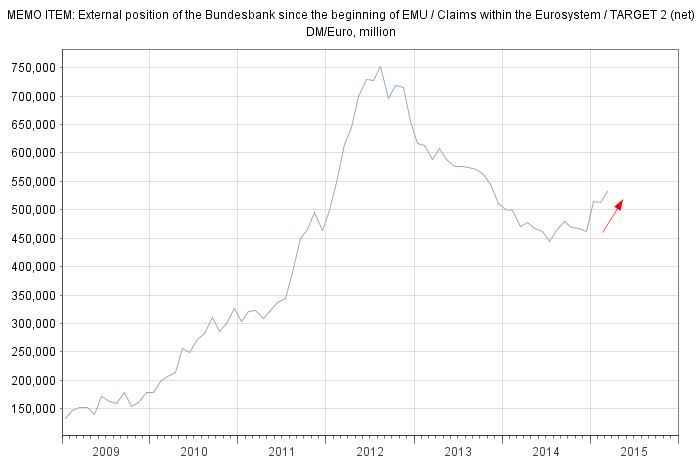

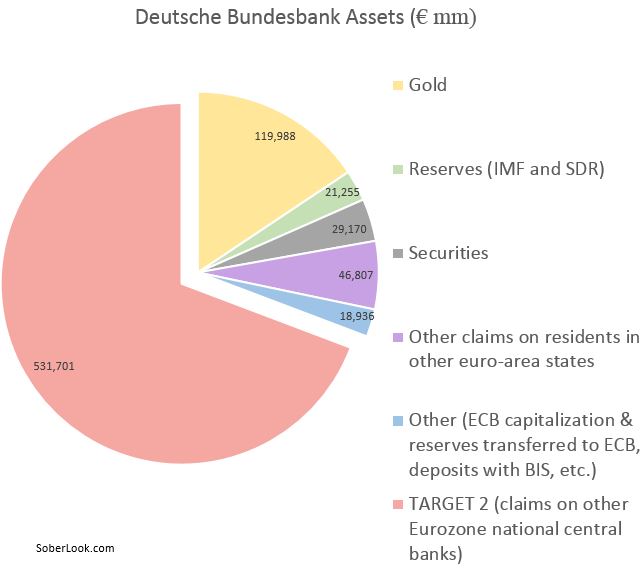

So if the Bank of Greece is borrowing, who is doing the lending? The funds come from the other euro area central banks (via the Eurosystem), particularly the Bundesbank. We can see the increase in this exposure to Greece on Bundesbank's balance sheet. As the Greek citizens are removing funds from their banking system (including taking out bank notes), this balance sheet item at Bundesbank rises further.

|

| Source: the Bundesbank (the latest increase is almost entirely due to Greece) |

In a Grexit scenario, as the Bank of Greece is expelled from the Eurosystem, it will default on its TARGET2 obligations. That in turn will force Bundesbank (and other core euro area central banks) to take a write-down. Of course a nation such as Germany should easily absorb such a loss and recapitalize its central bank. But at that point the Germans will surely want to know just how much more of such exposure their central bank holds.

The answer at this point is that nearly 70% of Bundesbank's assets are in TARGET2 claims - a half a trillion euro exposure to periphery nations' central banks. How much support for the EMU will the Germans have once they realize that a large portion of their central bank's assets could be at risk? After Grexit, the TARGET2 exposure will no longer be some abstract concept - the risk levels will become quite real and German politicians and the media will surely drive that point home.

Moreover, as Greece imposes currency controls, depositors in other periphery nations are likely to also begin shifting capital out of their domestic banking system - as they see the writing on the wall. Portugal, Spain, and Italy are particularly vulnerable. Such actions will of course end up increasing TARGET2 imbalances further (as was the case in 2012), putting more of Bundesbank's balance sheet at risk. Contagion could become a major problem again. We already see some early signs, as periphery bond yields rose last week in spite of all the QE buying efforts.

Certainly Grexit related damage can be managed by the national central banks and the European Stability Mechanism. These institutions will be promptly recapitalized. Such actions however will anger citizens of some member states, whose taxpayers' funds will used to fix the damage caused by Greece. Given the chaos and the political backlash such an outcome will generate, it's unclear when - if at all - confidence in the currency union will be restored. As discussed before (see post), history is not on the Eurozone's side.