When looking at the bond market or eurodollar futures, both tugged by JPY, I don’t think it was just the payroll report that pushed new levels of anti-reflation today. Instead, there is too much that is consistent with a weak payroll report, and by that a mean a string of them. Yesterday, for example, automakers released their sales estimates for the very important month of May. Memorial Day looms large on their calendar and can often set the tone for the summer season.

Instead, it was another largely negative month. If GDP and all its constituents suggested weakness in just Q1 (transitory as always) as Janet Yellen’s FOMC still believes, then auto sales are perhaps the most salient counterpoint that such “headwinds” persist even this far nearly halfway into 2017. We are right back in 2014 again, where such mysterious inconsistencies abound at least in the mainstream:

May’s results sealed the first three-month stretch since 2014 during which the monthly sales pace fell short of 17 million. The lack of consumer demand even amid readily available financing, low gasoline prices and strong job growth belies underlying weakness within the market.

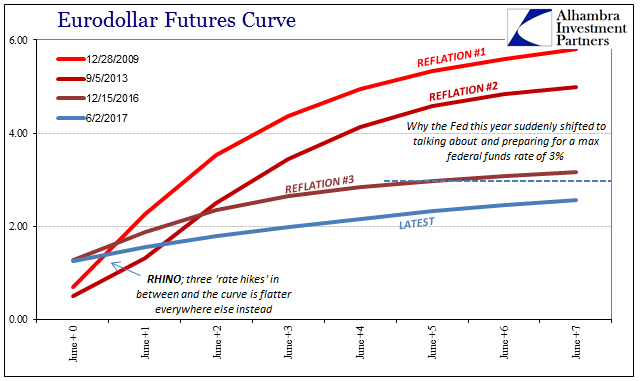

“Strong job growth” wasn’t true then, and now in 2017 it is more and more difficult to even suggest it. The labor market has slowed to a considerable degree over these last three years (from what starting point isn’t yet known for sure, but I have little doubt it wasn’t ever nearly as good as was claimed and estimated) which is now consistent with everything including persistently weak auto sales. Therefore, markets are getting out of the “reflation” mood, not that they were very far into it at any time.

The real point is to ask what do we have to show for it all? Four QE’s, trillions in bank reserves, six years of ZIRP and still near zero and nothing like normalcy; what did we get out of it? I asked that very question all the way back in March 2012.

When the FOMC decided to implement ZIRP in late 2008, they did so because their models calculated the trade-offs as positive. Recently, as the Fed’s models badly underestimated economic “headwinds” (a term from 2011 that I have little doubt we will be hearing again in the coming months), convincing the FOMC to keep ZIRP until 2014 (and likely longer), they did so because their models quantified the expected impacts of doing so. Those impacts take the form of an explicit tradeoff, and I would hope, at the very least, the models’ recommendations were implemented because they had quantified both the up and the down…

We already know they have badly overstated the upside. Challenging the downside to the acknowledged trade-off is the only way to finally begin an accounting or cost/benefit of all this unconventional monetary policy.

If the economy does not truly improve from its last downturn in 2015-16, there is no plausible way to suggest any of that monetary “stimulus” will ever achieve anything positive whatsoever. We have been left in a chronic state of weakness, where the best of it is nothing more than sentiment and positive feelings almost entirely derived from “they have badly overstated the upside.”

The downside as we are still experiencing has yet to be fully discovered. That doesn’t mean recession as we are conditioned to expect, but much worse. An economy that doesn’t actually grow is decidedly more dangerous than one that temporarily stops then picks back up. That was true in 2012 and should have been evident even then by nothing more than a second, then a third (and then of fourth) QE. If you have to do it more than once, it doesn’t work. If it doesn’t work, the possibilities are all that much more difficult (even if you believe in QE).

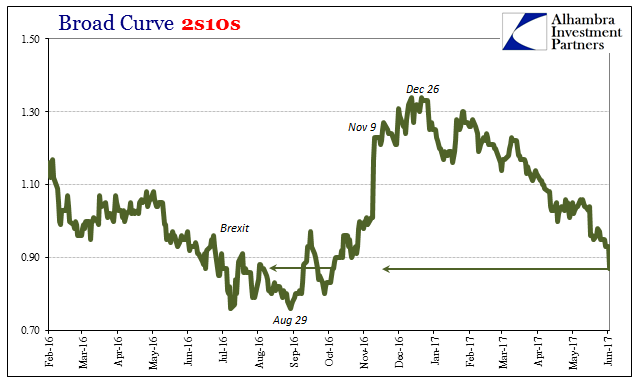

Autos were the one part of this wretched economy that seemed to be legitimately positive, actually doing well rather than being described using tortured language as “strong.” Ten years is a very long time to be without growth, stuck in a state of non-linear contraction. Take away the one part that was contributing positively, the chances of another set of years, maybe another ten, in the same state can only go up. It is not hard to appreciate why despite “interest rates have nowhere to go but up” the yield curve (or eurodollar futures curve) has collapsed back to mid-2016 levels of long-term liquidity preferences.