Kerrisdale Capital is short shares of Astra Space (NASDAQ:ASTR), a $2 bln space launch company formed at the peak of the 2021 SPAC bubble—with no revenue, no track record of reliability, and no established market for its undersized vehicle. A story stock that’s yet another example of the questionable businesses going public via SPACs, Astra faces massive obstacles in its quest to develop a viable business model.

Astra is poorly positioned within an overcrowded market for small launch vehicles. Its main competitors will soon be launching larger 1,000kg+ payload rockets while Astra has yet to overcome developmental hurdles necessary to successfully launch even a single satellite into any of the emerging broadband mega-constellations.

Shortly after Astra announced its SPAC merger, the company increased its payload capacity goal (not a trivial matter in rocket programs) and signed a “secret” deal with a competitor for access to some of the competitor’s more powerful engine IP—both clear signs that Astra is struggling to keep pace with market leaders.

Moreover, Astra shortsightedly relies on cheap, off-the-shelf commercial parts—a strategy that precludes it from exploiting the economic advantages that its more sophisticated competitors enjoy by developing reusable rockets that in the long run reduce expenses. Consequently, Astra remains strikingly vulnerable to the relentless price deflation that characterizes today’s launch market.

Astra’s investor pitch boils down to selling the pipedream of an unprecedented number of cheap rocket launches. Astra’s forecast calls for 300 launches per year by 2025, a whopping 10x more than SpaceX achieved in 2021. Management markets this exceptionally aspirational goal (which we view as pure fantasy) in a bid to spread its expensive Bay Area manufacturing costs over enough rockets in order to turn a profit.

A reality check is in order: To date, Astra has managed just one successful orbital test flight. If Astra’s five-year projection of almost daily successful launches of rockets made with non-aerospace grade parts does not sound improbable enough, it ignores an even graver problem with Astra’s projection—not one expert whom we interviewed, nor any independent market study we reviewed, offered any reason to think that, industry-wide, sufficient market demand will exist for Astra to sustain approximately daily launches by 2035, let alone 2025.

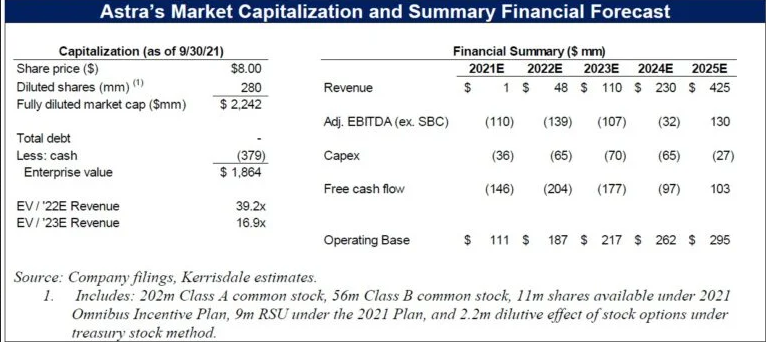

From an execution standpoint, Astra is already exhibiting tell-tale signs of a company that’ll never fulfill its cosmic promises. FY21 EBITDA guidance of negative $(110)m is -35% lower than projected at the start of the year. Post-merger cash on hand—originally touted as sufficient to fully fund the company until daily launch in 2025—is now only enough to cover monthly launches in 2023, meaning Astra will almost certainly need to tap the capital markets in the upcoming year.

We’re skeptical that public investors will stick around at the current valuation to underwrite Astra’s tenuous business prospects, and the lock-up expiry of 91m shares tomorrow could result in near-term volatility. As Astra encounters inevitable setbacks, hemorrhaging cash in hopes of developing a rocket that is undersized and lacking demand, its shares valued at the height of the SPAC boom should tumble further to the ground.

Astra’s rocket launch projections are nonsense. No market analysis supports Astra’s planned 300+ launches by 2025. Excluding satellites from SpaceX and China from industry-wide forecasts, there is insufficient demand to support even a fraction of Astra’s aggressive forecast.

Large launch vehicles are a more efficient and cost-effective solution to deploying whole orbital planes versus piecemealing coverage through a series of small launches and will dominate the market for mega-constellations (which are widely expected to comprise the bulk of all satellites deployed over the next decade). Only scraps will remain for Astra and all the other smaller launchers—far less than Astra needs to turn a profit.

Astra is falling behind its competitors. Multiple industry executives we interviewed, who routinely secure launch services for small satellite manufacturers on a global basis, agree that Astra’s rocket dimensions and payload capacity are well below the “sweet spot” of customer needs.

Rocket Lab USA (NASDAQ:RKLB), Relativity, ABL, and Firefly all have plausible plans to produce 1,000kg+ rockets that will be entering the market in the near term; by contrast, Astra aspires to produce a 500kg rocket two years from now. Astra’s attempt to catch up is self-evident.

Shortly after its SPAC announcement, Astra publicly disclosed (without any credible technological explanation) an increase in the targeted capacity of its rockets; shortly thereafter, and surely to Astra’s embarrassment, the public learned that Astra had entered into an agreement allowing it limited access to study one of its competitor’s rocket engine IP in exchange for $30m.

Expect many more failures as Astra ramps up its launch efforts. Astra is playing a risky game. It needs to ramp production and prove reliability of a cheaply built rocket while maintaining access to public markets to fund cash burn. We believe Astra’s reliability goal for its rockets is 80% (which itself is not exactly confidence inspiring).

According to a well-informed source, however, at its current stage of development, the rate of Astra’s rockets failing may be as high as 1 in 2. Should Astra encounter even one high-profile failure, considerable damage to Astra’s reputation and development plans seems inevitable.

Six months into public life and Astra has already missed expectations. Like many other 2021 vintage SPACs, Astra has already badly missed its financial forecasts, and will likely continue to do so. 2021 EBITDA will come in -35% below original SPAC forecasts, and even with the benefit of delayed capex, Astra is burning cash at a rate of $50-$60m per quarter.

Even only 5 months after closing a deal that placed nearly $500m of cash on Astra’s balance sheet, the company has already walked back “being fully funded to 2025” and instead indicated it will only have enough cash to get through sometime in 2023.

Astra’s strategic direction lacks differentiation and raises concerns. Recent M&A and a broadband constellation announcement smack of trying to run SpaceX’s playbook—but without any of SpaceX’s resources and without having first established basic launch reliability.

Apollo Fusion technology is too slow to be an attractive orbital transfer vehicle in LEO and ferrying small satellites to GEO and beyond is a nascent, niche market.

If the objective is to use Apollo Fusion for Astra’s own constellation, as contemplated by the company’s recent V-band application, investors should be questioning the purpose of a costly mega-constellation that is years behind Starlink, Project Kuiper, OneWeb, and Telesat.

The Space SPAC boom has bust. Of the 8 new space SPAC mergers that have closed in the last 6 months, 7 are trading below the SPAC IPO price, with an average decline (excluding Astra) of -38%.

Astra’s market capitalization is still over $2bn despite a business model more unproven than many of its space SPAC peers. On Dec. 30, 91.2m shares unlock, twice the current float, posing additional downside risk in an unforgiving tape for pre-revenue speculative stocks.