EU leaders have granted an extension to the Article 50 negotiating period, piling the pressure on the UK Parliament to agree a way forward on Brexit. The question is: will a majority of British MPs settle on a course of action before the EU’s 12 April deadline?

By James Smith, Developed Markets Economist

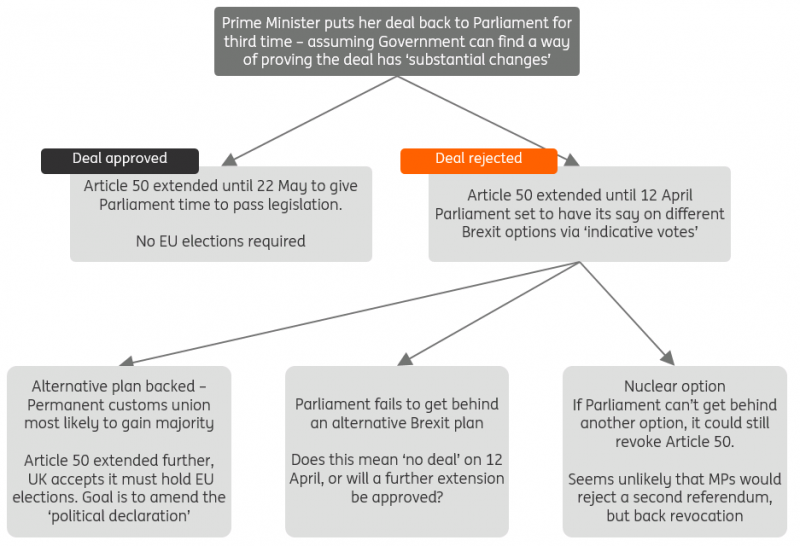

The new Brexit timeline

What's been agreed?

After a classic marathon evening of talks at the March European Council meeting, EU leaders have agreed to an extension of the two-year Brexit Article 50 negotiating period. The decision, being dubbed a "flextension", gives the UK two options and piles the pressure on Westminster to agree a way forward over the next few weeks.

If May's Brexit deal is passed next week, the EU will grant an extension that lasts until 22 May - the day before European Parliament elections. This would give the UK time to pass the relevant legislation.

If the deal doesn’t pass next week, then the UK will have until 12 April to decide a way forward. This coincides with the legal deadline for the UK to give notice on holding EU elections, and European Council President Donald Tusk made it clear that this was a key condition to unlock a longer extension beyond mid-April.

Before going into the implications, there is immediately some good news. There had previously been reports that the EU was considering holding a further summit next week to make the final decision on extending Article 50, which would come after May's third meaningful vote on her deal.

Perhaps fearing the risk of taking the Brexit saga to the eleventh hour, leaders decided against putting off the decision until next week. This takes some of the heat out of what could have been a nerve-wracking week, although Parliament still needs to get its act together and formally change the exit date in UK law before 29 March (although this shouldn’t be too hard).

Will May’s deal go through next week?

In short, probably not.

The momentum that seemed to be gathering behind May's deal last weekend appears to have faded. The Prime Minister's hint that she wouldn't be prepared to delay Brexit beyond June has altered the calculation facing MPs again, and many pro-Brexit hardline lawmakers may decide to hold tight in the hope that a 'no deal' outcome has become more likely. Talks with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), who are seen as key to unlocking wider support for Theresa May's deal, also seem to have stalled

Of course, in order to have a vote in the first place, the Prime Minister needs to find a “substantial” change to the deal, to satisfy a requirement put forward by Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow earlier in the week.

At an event held by the Netherlands-British Chambers of Commerce (NBCC) on Thursday, Brexit Minister Robin Walker reiterated that the government is confident it can navigate the Speaker's requirements. The government could argue that the EU’s Article 50 statement, combined with further crystallisation of Brussels' Brexit 'reassurances' from last week, could be cast as a 'substantial change' to the deal. If the government can also get a significant number of MPs to sign the motion, it hopes it can signal there is a will in parliament to hold a repeat vote.

However, the fact that the government is having to use these rarely-used mechanisms to force 'meaningful vote three' demonstrates that it will be very tricky for the Prime Minister to hold further votes on her deal again. Lawmakers will therefore be aware that this might be their last opportunity to vote on May's deal. Those Brexiteers that calculate a long delay is inevitable may therefore still decide to back it, while those more moderate MPs that fear ‘no deal’ may also decide to get behind it - although we suspect there will be nowhere near the numbers needed for May to get her deal passed.

Will parliament agree on an alternative plan before 12 April?

Assuming May's deal is rejected for a third time, focus will switch back to this idea of 'indicative votes' - a process where parliament will get its say on alternative Brexit options. Backbench MPs have put down an amendment for Monday, which will try to force these indicative votes later in the week.

If these votes do take place - which we suspect they will - the question is what, if any, option will get parliamentary backing?

A second referendum still lacks numbers, not least because a number of Labour MPs are wary given they represent leave-supporting areas. The so-called 'Norway Plus' option, which would essentially involve single market membership, could also lack majority support because of concerns surrounding free movement of labour.

The most likely option to get a majority is a permanent customs union. This alternative, that would avoid the need for tariffs/rules of origin issues in future, is not different to the current deal. The contentious Irish backstop includes a customs union, and in theory, when push comes to shove, many of the more moderate Conservative/Labour MPs could get behind it.

That said, this will really depend on how pressurised lawmakers feel. If the heat is taken out of the situation, for instance, if MPs still perceive the risk of 'no deal' to be minimal, then it's possible that 'party politics' will prevail. A permanent customs union is the Labour Party's policy, so some Conservative MPs may still be reluctant to get behind it.

Either way, the sequencing of these votes will be key. Advocates of the different options will want their plan to be voted upon last. The logic here is that if every other option is rejected, MPs may possibly judge the last one on the table to be their last opportunity to take Brexit in a 'softer' direction.

What happens if the UK hasn’t decided on anything by 12 April

This is a real risk, given that May’s deal is unlikely to pass, and there are no guarantees a different option will get a majority in indicative votes.

So what would the EU do if the UK came back just before 12 April asking for a further extension? Most commentators tentatively agree that the EU doesn't want to be blamed for no deal so may still be open to a second extension (as long as the UK holds the elections) even if the reason for doing so is a bit flimsy.

That said, Rem Korteweg from the Clingendael Institute told the NBCC forum on Thursday that some EU figures now view a 'no deal' Brexit as a "clean option". The logic is that it gives business certainty sooner (as bad as that certainty may be), and also avoids Brexit becoming a distraction in what is a key year for Brussels. After all, if the UK is to stay in for longer and participates in European elections, British MEPs will get some sort of say in the appointment of top jobs at the big European institutions - something which is not desirable for some Brussels officials.

In the end, we think the British Parliament will do all it can to avoid a 'no deal' Brexit - most likely by settling upon some kind of alternative plan, or even by taking the 'nuclear option' of revoking Article 50 altogether (less likely). We also suspect that most in the EU will continue to view a 'no deal' Brexit as highly undesirable.

We therefore still think 'no deal' will be avoided, although the odds of this happening on 12 April have undoubtedly increased.

Content Disclaimer

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more