- Midway through its third adjustment programme, for which it has already received a little more than EUR 30 billion out of a maximum of EUR 86 billion, Greece is seeking to conclude negotiations on the bailout’s second review, which would pave the way for the unblocking of a third tranche of funding.

- The Eurogroup meeting held earlier this week failed to reach a political agreement. A solution will eventually be found as each party makes concessions, although the size of these efforts has yet to be determined.

- The country is not threatened with a short-term liquidity crisis. Even so, this latest episode reveals that even though Greece’s economic parameters are relatively favourable, from a political standpoint, it is never far from outbreaks of stress and the dramatization of all that is at stake.

The 20 February Eurogroup meeting showed that Greece and its creditors have not given up on the possibility of reaching an agreement, even though they still failed to do so. Although teams from the IMF and the European institutions will be returning to Athens soon to pursue discussions, Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem was careful to point out that a “political agreement” had not been reached between the different parties attending the meeting. The goal is still to complete the bailout’s second review, which would pave the way for the release of a new tranche of the bailout programme.

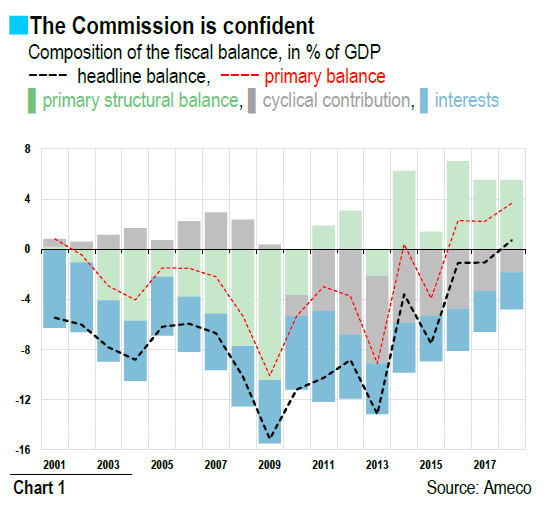

The current bout of stress arises from a fundamental disagreement between the Europeans and the IMF. The European Commission has adopted a rather optimistic vision of Greece’s economic situation, as illustrated by its winter economic outlook. EC departments highlight Greece’s 2016 results, which were better than expected in terms of GDP growth (+0.3%) and public finances (primary surplus of more than 2% of GDP). The Commission is looking for a robust recovery this year (+2.7%) and in 2018 (+3.1%). Under these conditions, it should not be too hard for the country to meet its high primary surplus targets (3.5% of GDP in 2018). European creditors, especially Germany, are quick to use these observations to justify postponing debt restructuring talks. As long as debt relief remains is sight but is not achieved, the Greek authorities remain under pressure. The creditors also hope to put off a very costly political decision as long as possible.

It has been clear for months now that the IMF does not share in this analysis. Although the latest economic statistics show a real but fragile recovery1, IMF experts point out that one-off revenue made a big contribution to the improvement in public finances. Looking beyond a short-term catching-up movement, Greece’s growth potential is apparently not very high. Lastly, although they esteem that the pension system is placing an excessive burden on the Greek economy, in terms of fiscal policy, they do not think it would be productive to try to obtain now more than the package of measures already approved at the beginning of the programme. The IMF’s position can be summarised as follows: “Greece cannot grow out of its debt problem.” This implies that the solvency of the Greek state depends on substantial debt relief provided by its European creditors (ESM, EFSF).

There is nothing new about this fundamental disagreement. Three solutions have been considered in recent months to break the deadlock:

1. The European programme continues without the IMF, based on the European institutions’ economic parameters. There are a lot of arguments to support this position. The Washington-based IMF has already lent Greece enormous sums by its own standards, and it is not necessarily “begging” to increase its involvement. As to the Europeans, the funding shortfall would be rather painless considering the amounts at stake: press reports are talking about EUR 5 billion that the IMF might lend to Greece as part of the third bailout package of EUR 86 billion3. Moreover, some stakeholders are not particularly

in favour of the IMF’s implication in the bailout and adjustment mechanisms for the eurozone countries. Considering the firepower of the European Stability Mechanism, and the expertise of the European Commission and the ECB, the Europeans should be able to settle their affairs on their own, perfectly autonomously.

For all these reasons, we have long thought that this would be the most probable outcome: the IMF would continue to provide technical support to the Europeans without entering financially into the third bailout programme. The withdrawal would be discreet as it would be done simply by preserving the statu quo (the 3-year programme has been proceeding without the IMF for the past 18 months). Yet it seems we overlooked the tougher stances taken by several European executives, foremost of which is Germany, who affirm that their parliaments will no longer approve the bailout without the IMF’s participation. This position is paradoxical since the IMF’s quasi-forced participation would hardly strengthen the current programme’s credibility in circumstances where fundamental disagreements are patent between the IMF, who esteems that debt relief is essential and urgent, and the German authorities, who find that the timing is inopportune, and might not even be necessary.

2. The IMF bends under European pressure. Since summer 2015, very strong pressure is exerted through the media, which suggest the IMF is the one that is always demanding more austerity during bailout negotiations, and through the European representatives on the IMF’s Executive Board4. This practice has its limits, however: a press release earlier this month shows that the majority of Board members support the positions of IMF staff. And this is before the Trump administration appointed its Board representative. On the whole, IMF teams have proven to be very resilient so far. If the IMF ends up participating in the programme, it will only be after winning some major concessions. For example, the Europeans might have to agree to quantify future debt relief efforts, on condition, of course, that the programme is successfully completed in 2018.

3. Under the third option, Greece would try to satisfy both the EC and IMF. If push comes to shove, the IMF might agree to participate in a plan in which debt sustainability is assured primarily by very high fiscal surpluses (3.5% of GDP before interest charges, for several years after 2018), rather than substantial debt relief by European creditors. In this case, the IMF might ask the Greek authorities to immediately enact measures designed to sustain the primary surplus at high levels, by emphasising what it sees as the main weak points of the country’s public finances: a deficit-ridden pension system and an excessively narrow tax base. So far, Alexis Tspiras has refused to consider reform legislation that would take effect after the European programme closes. Yet a few statements made at the end of this week’s Eurogroup meeting suggest that this idea is still on the table. Christine Lagarde’s statements after meeting with Angela Merkel mid-week also point in this direction. Although she is still very firm about the need to allow the country to benefit from debt restructuring, the IMF’s Managing Director said she is much more confident that an agreement can be reached after seeing the progress the Greek authorities have made towards satisfying the demands of its creditors.

Of the parties present at the meeting, it is in the interest of none to see the situation deteriorate any further, or to replay summer 2015 events. In the end, an agreement will probably be reached. If each party were to make concessions, the agreement could be a synthesis of the three options outlined above, although the mix would still have to be determined. From this perspective, it is worth noting that Alexis Tsipras is undoubtedly in the weakest position5.

As to the timing, the Eurogroup president pointed out that even though current delays were harming the country’s economic recovery by eroding confidence (and risk fostering another build-up of government arrears to the private sector), the country does not face any major repayment dates before the second half of July, and is still far from a liquidity crisis. The real urgency is much more political.

by Frédérique CERISIER