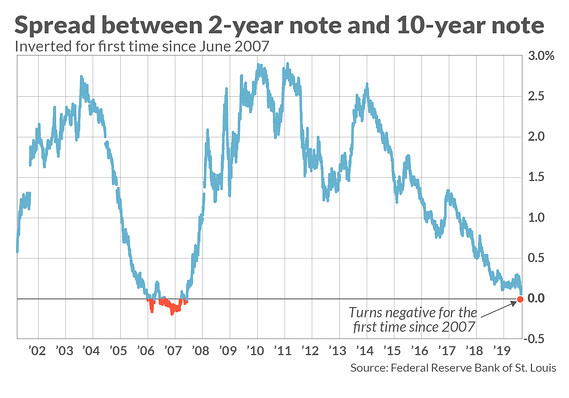

One of the crowd’s favorite yield curve pairings (the spread on 10-year less 3-month Treasuries) has been signaling elevated US recession risk since May. As of yesterday (Aug. 14), the 10-year/2-year spread has gone over to the dark side too. That alone doesn’t insure that economic output will slump in the near term, but it’s a clear message that the crowd has increased its collective bet that a US downturn is approaching.

It’s all about the market’s probability estimates rather than fate. But if you’re inclined to consider yield curves’ implied economic forecasts, the sight of two widely followed spreads in below-zero terrain is worrisome. As outlined by The Capital Spectator recently, history suggests that recession warnings are more compelling when both the 10-year/3-month and 10-year/2-year spreads are flashing red.

Despite the stronger signals for expecting an economic downturn, some analysts aren’t drinking the Kool-Aid, at least not yet. Viktor Shvets, head of Asian strategy for Macquarie Commodities and Global Markets, for instance, remains skeptical that the economy has crossed the macro Rubicon. “My view has always been that yield curve predicts absolutely nothing,” he tells CNBC. “What it does tell you (is) that you will have a recession if you don’t do something about it.”

Here’s where it gets interesting. Historically, the Federal Reserve has been slow to read the tea leaves and roll out counter-cycle monetary policy. Is this time different? No one really knows at this point, although some business-cycle observers think that the central bank may be more proactive going forward compared with its history.

That’s a possibility worth entertaining, advises Tim Duy, a veteran Fed watcher who’s also an economics professor at the University of Oregon. “This cycle is unusual in that the Fed has cut rates already; in the past, they have continued to hike rates after a 10s2s inversion,” he explains. “I don’t like to say ‘this time is different’ given the yield curve’s past predictive ability, but the Fed’s response is different, and only time will tell if the early response is sufficient to avoid recession.”

Meantime, a bit of perspective is in order. First, the US economy continues to expand. Growth has slowed, but a broad reading of economic indicators continues to suggest that the expansion endures. As outlined in this week’s edition of The US Business Cycle Risk Report, a broad measure of the US macro trend remains modestly positive. The current median nowcast for US third-quarter GDP growth is +1.9%, based on several sources. That’s a slow-bordering-on-sluggish pace, but it’s only fractionally under Q2’s modest +2.1%.

Keep in mind, too, that the inverted yield curves are predicting a recession. The conventional view is that inversion precedes a downturn by 12 months, give or take. On that basis, the key question is what happens in the intervening 12 months? Does the Fed pull a monetary rabbit out of its hat to minimize recession risk? Does the Trump administration, fearing a weak economy as next year’s election nears, decide to resolve the US-China trade war and give the economy a boost via a burst of positive sentiment?

The counter argument is that interest rates are already so low, and monetary stimulus still strong, that the Fed’s hands are effectively tied for sidestepping an oncoming recession with more policy changes. There’s also the worry that Europe is slipping into recession and China’s growth is slowing and so the global headwinds have already sealed the US economy’s fate. Another line of thinking is that the global economy is mired in extreme levels of debt built up over the last decade and this dead weight will counteract any effort by central banks to forgo the inevitable.

One thing that every can (or should) agree on is that the recession risk is rising for US. But until the hard data, via a broad spectrum of indicators, agrees with the yield-curves’ forecast, it’s premature to assume that the future is written in stone. That said, the window of opportunity for keeping the expansion alive is closing – perhaps two to three months at most.

What happens next, or doesn’t, will likely determine if the US continues to grow at a slow/sluggish pace or begins to contract. The bond market (supported by a plunging stock market) are all-in on the recession outlook. The only mystery is whether the incoming data in the weeks and months ahead will confirm (or reject) the forecast.

For the moment, there’s still a conflict – the official economic numbers continue to reflect growth, albeit slow growth. But hard data arrives with a lag. The markets, by contrast, are updated in real time (as are their forecasts). But markets aren’t perfect. Squaring this circle will take time. Plan accordingly.