Since the mid-90's there has been an ongoing debate waged between "passive indexing" and "active management" of portfolios. The primary point of contention is "why pay a manager a fee to actively manage a portfolio when [x%] of managers fail to beat an index fund over [x period]." On the surface, this certainly sounds like a reasonable argument for ditching all of your actively managed mutual funds and buying an index fund. However, is that really the best thing for you to do?

A recent article by George Sisti entitled "Whack-a-mole fund managers can't beat index funds" is a good example of the overall debate. He states;

"Proponents of active management claim that gifted managers can identify stocks that will rise in price and shun those that will decline. They can sell stocks in advance of any serious market decline and re-enter the market before the rebound, thereby outperforming their benchmark index. Let's look at a recent report that debunks these claims.

Standard & Poor's recently released its year-end 2013 S&P Indices Versus Active Funds (SPIVA) Scorecard that compares the performance of actively managed mutual funds to their S&P benchmark indexes. For the five years ending on Dec. 31, 73% of large-cap domestic funds, 78% of midcap funds, 67% of small-cap funds and 80% of REIT funds underperformed their benchmark indexes. Almost two out of three actively managed domestic stock mutual funds underperformed the S&P 1500 total stock market index over the past five years."

There you have it. Clear evidence that you should just buy an index fund, shut up and go home. However, there are several issues with the analysis.

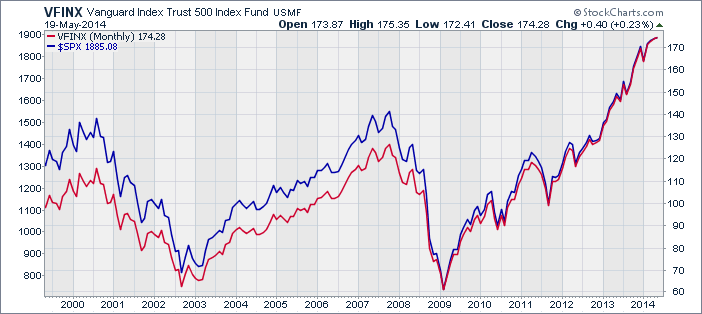

First, there is NO fund manager alive that can beat an index fund every year, year-after-year, over a long time period even if they simply mimicking the index. This is clearly shown by comparing the Vanguard S&P 500 Index fund as compared to the S&P 500 Index.

The differential in performance over time is due to the advantages an index has over a fund.

An index:

- Has no trading costs

- Has no expenses to pay (Employee related costs, building and infrastructure costs, etc.)

- Pays no taxes

- Benefits from share buybacks

- Benefits from the substitution effect

- Does not have to compensate for redemptions or liquidity flows

You get the idea. Like a Unicorn, the benchmark index is a mythical creature that only exists in our imaginations. Yet, the index is used as a point of comparison to berate investors into competing for a prize they can not win. As I have stated in the past:

Comparison is the cause of more unhappiness in the world than anything else. Perhaps it is inevitable that human beings as social animals have an urge to compare themselves with one another. Maybe it is just because we are all terminally insecure in some cosmic sense. Social comparison comes in many different guises. ‘Keeping up with the Joneses,’ is one well-known way.

If your boss gave you a Mercedes as a yearly bonus, you would be thrilled—right up until you found out everyone else in the office got two cars. Then you are ticked. But really, are you deprived for getting a Mercedes? Isn't that enough?

Comparison-created unhappiness and insecurity is pervasive, judging from the amount of spam touting various enlargement procedures for males and females. The basic principle seems to be that whatever we have is enough, until we see someone else who has more. Whatever the reason, comparison in financial markets can lead to remarkably bad decisions.

Comparison in the financial arena is the main reason clients have trouble patiently sitting on their hands, letting whatever process they are comfortable with work for them. They get waylaid by some comparison along the way and lose their focus. If you tell a client that they made 12% on their account, they are very pleased. If you subsequently inform them that “everyone else” made 14%, you have made them upset. The whole financial services industry, as it is constructed now, is predicated on making people upset so they will move their money around in a frenzy. Money in motion creates fees and commissions which further detracts from investor returns. The creation of more and more benchmarks and style boxes is nothing more than the creation of more things to COMPARE to, allowing clients to stay in a perpetual state of outrage creating more revenue for Wall Street.

Secondly, Mr. Sisti's article is a function of selective data mining. He points to the 2013 report by Standard & Poors as definitive evidence that indexing is a better way to invest. The problem is that it only looks back at a 1, 3 and 5 year return period. Of course, the last 1, 3 and 5 year period has been a run-away freight train of liquidity induced returns courtesy of your friendly neighborhood Federal Reserve.

By only looking at a market period where stocks are rising, doesn't really give credit to where active fund managers should really shine - which is capturing some upside return when stocks are rising and not losing as much when the markets are falling. Therefore, in a rising market, and factoring in for fees, taxes, expenses, etc., it should not be at all surprising that over the last 5 years actively managed funds have underperformed an index.

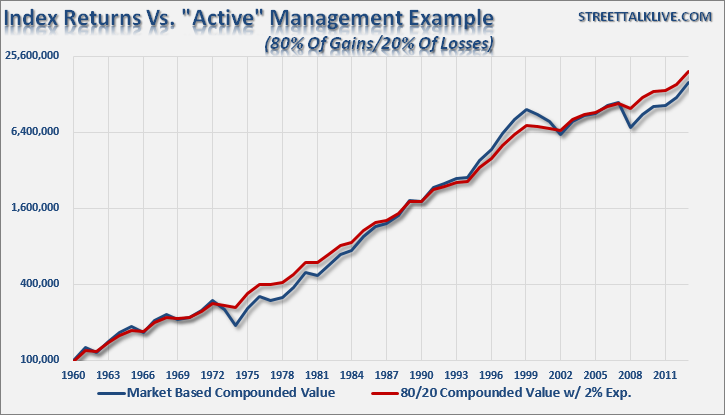

Over longer periods of time, however, that story changes. Let's create a fund that underperforms the index by 20% when markets are rising and loses 20% of every market decline. Also, let's include a 2% annual expense to cover fees and other trading related costs which are not included in the index.

The most crucial point to understand is that the MAJOR contributing factor to winning the long term investment game is NOT LOSING value when the markets decline. As shown above, even when including a 2% annual drag on portfolio returns over the extended investment period, not losing capital during market reversions led to a larger ending portfolio value than indexing alone.

Lastly, while the majority of "actively" managed funds are managed to a degree, most have now become "closet index funds." Fund managers are very cognizant of "career risk" which is due to mainstream analysis that focuses on short term performance rather than long term investment disciplines. Underperformance, particularly in an up year, leads to outflows of investor capital from fund managers reducing their profitability. Mr. Sisti unwittingly acknowledges this point in his analysis:

"Propagandists for active management have a ready excuse for these disappointing results. They admit that it is difficult for fund managers to outperform index funds during rising markets. A rising tide floats all boats and the upward trajectory of a bull market creates an ideal environment for passive investors. But all bull markets eventually end and advocates of active management assert that this is when investors in actively managed funds will be rewarded.

Yet according to the year-end 2009 SPIVA Scorecard, 49% of large-cap funds, 74% of midcap funds, 63% of small-cap funds and 52% of REIT funds underperformed their benchmark indexes for the three-year period 2007 through 2009. At the time, 54% of all actively managed domestic stock funds underperformed the S&P 1500 Total Stock Market Index. Active managers, as a group, failed to fulfill their promise to protect investors during the financial crisis. The theoretical opportunity to outperform stock market indexes doesn't often translate into reality."

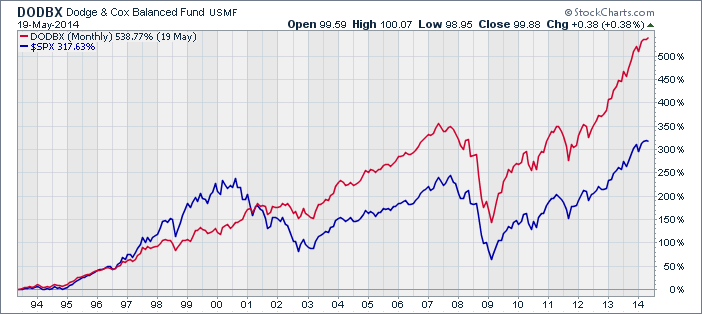

In other words, 46% or nearly half, of all active fund managers outperformed their respective benchmarks during the financial crisis where ALL asset classes were under attack. 51% of large cap funds outperformed as well. An investor focused on long-term investment discipline, risk management, capital preservation and long term returns could easily search and find one of those managers. I did a quick search of funds that fit that profile which had at least a 20-year history. Dodge & Cox Balanced Fund fit that profile. The chart below shows the performance of the fund (which owns both stocks and bonds) relative to the S&P 500 (all equity) index.

Where would you rather have been invested on a "buy and hold" basis?

Of course, that brings up the final issue which is "investor psychology" of which the chart above is a prime example. While the chart shows that investors would have almost doubled their value by staying with Dodge & Cox since 1993, the reality is that by listening to people like Mr. Sisti they would have dumped their fund between 1998 and 2000 to chase the S&P 500. This would have cost them dearly during the coming bear market. That lost value has yet to be recaptured.

Unfortunately, the reality is that investors rarely do what is "logical" but react "emotionally" to market swings. When stock prices are rising, instead of questioning when to "sell," they lured in near market peaks. The reverse happens as prices fall leading first to "paralysis" and then "hope" that losses will soon be recovered. Eventually, near market bottoms the emotional strain is too great and investors "dump" shares at any price to preserve what capital they have left. Despite the media's commentary that "if an investor had 'bought' the bottom of the market..." the reality is that few, if any, actually did. The biggest drag on investor performance over time is allowing "emotions" to dictate investment decisions. This is shown in the 2013 Dalbar Investor Study, which showed "psychological factors" accounted for between 45-55% of underperformance. From the study:

"Analysis of investor fund flows compared to market performance further supports the argument that investors are unsuccessful at timing the market. Market upswings rarely coincide with mutual fund inflows while market downturns do not coincide with mutual fund outflows."

In other words, investors consistently bought the "tops" and sold the "bottoms."

There are very important differences between your investment portfolio and a benchmark index.

1) The index contains no cash

2) It has no life expectancy requirements - but you do.

3) It does not have to compensate for distributions to meet living requirements - but you do.

4) It requires you to take on excess risk (potential for loss) in order to obtain equivalent performance - this is fine on the way up, but not on the way down.

5) It has no taxes, costs or other expenses associated with it - but you do.

6) It has the ability to substitute at no penalty – but you don’t.

7) It benefits from share buybacks – but you don’t."

For all of these reasons, and more, the act of comparing your portfolio to that of a "benchmark index" will ultimately lead you to taking on excessive risk, making emotionally based investment decisions and losing capital and time. As I stated above, the index is a mythical creature, like the Unicorn, and chasing it takes your focus off of what is most important - your specific goals, time horizon and investment discipline. Investing is not a competition and, as history shows, there are horrid consequences for treating it as such. In the long run, if you achieve your own personal investment goals isn't that why you invested in the first place?