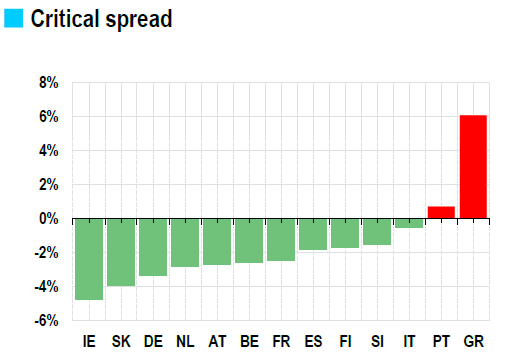

With the exception of Greece and Portugal, all Eurozone member states can now issue long-term bonds at a lower interest rate than their nominal trend growth rates.

- This situation is linked to the ECB loose monetary policy. It eases the debt reduction efforts of member states.

- When GDP growth is higher than the interest rate on the debt, the public debt ratio can decline even when there is a primary deficit.

In 2016, the public debt-to-GDP ratio should decline for the second consecutive year in the eurozone. Even though this figure is an average masking contrasting trends – between one group of countries in which debt is declining, dominated by Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Portugal, and other countries, like France, Italy and Spain, where debt continues to rise – a general trend is nonetheless taking shape. With the exception of Greece1 and Portugal, all Eurozone member states can issue long-term bonds at lower interest rates than their nominal trend growth rates (see chart 1).

This situation, linked to the ECB loose monetary policy, eases the debt reduction efforts of eurozone member countries. The change in the public debt to GDP ratio depends on two factors: 1) the critical spread, i.e. the spread between the interest rate on the debt and the nominal growth rate, and 2) the primary balance, i.e. the fiscal balance excluding interest payments.

A positive critical spread automatically drives up the public debt-to-GDP ratio: each year, interest payments as a percentage of GDP are higher than nominal GDP growth. Unless a primary surplus can offset it, the debt-to-GDP ratio increases only because of interest payments. This is known as the snowball effect Inversely, when the critical spread is negative, nominal GDP growth more than suffices to cover interest payments. The public debt to GDP ratio can decline even when there is a primary deficit as long as it does not exceed the surplus of revenues.

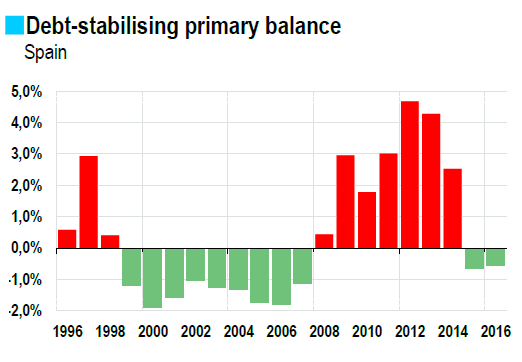

During the crisis, soaring risk premiums and the drop-off in activity triggered a major snowball effect in the peripheral countries. In Spain, for example, it accounted for nearly half of the increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio between 2011 and 2014. At the time, major primary surpluses (4-4.5% of GDP) were needed to stabilise the debt. Today, thanks to renewed growth and the ECB’s action, Spanish public debt – which has reached 100% of GDP – could level off with a primary deficit of 0.5% of GDP (see chart 2).

1 Greece cannot issue bonds on the markets. As part of the EU-IMF programme, it receives loans at very low interest rates, which are lower than its potential growth rate.

Critical spread

For each country, the chart shows the spread between the 10-year bond yield in May 2016 and the trend nominal growth rate. Trend nominal growth is calculated using the European Commission’s estimated growth trend in volume, to which we have added 2% inflation.

The chart shows at each period the primary balance necessary to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio in Spain.

by Thibault MERCIER