The March issue of Urba, the magazine of the Union des municipalités du Québec, presented a survey of Quebec municipal finances. Among other findings, it reported aggregate municipal debt of $21 billion as of the end of 2010. This was an attention-getting figure, amounting to a rise of almost 20% in just three years. No more was needed for some observers to sound an alarm. The Urba article took a calmer approach, speaking of the need to monitor the state of municipal finances. This is the spirit of our own survey of the situation.

Investment in public infrastructure has swung through a number of cycles since the 1950s. The rapid growth of the Canadian population in the postwar years brought a need for major infrastructure investment in the 1960s and 1970s. Quebec was no exception. In the Montreal area, Expo 67 and the 1976 Olympics drove infrastructure spending booms. Another factor in the ups and downs of investment by local, municipal and regional governments has been a succession of temporary shared-cost infrastructure programs launched by the federal and Quebec governments.

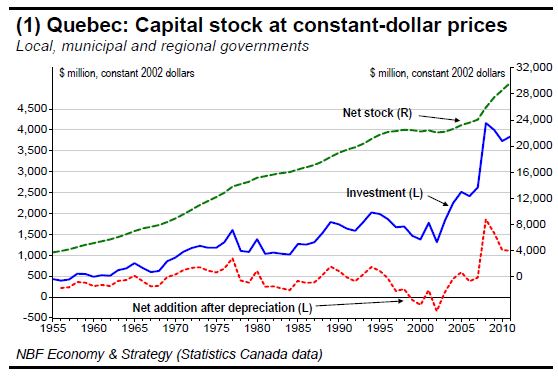

From the late 1970s through the mid-1980s, as chart 1 illustrates, municipal investment in Quebec (expressed in constant dollars) was essentially flat. Among the factors in this spending plateau were the recession of the early 1980s, high real interest rates and slower population growth. In 1994, the federal government entered into an agreement with each province in which it assumed about one-third of eligible costs. The agreement with Quebec provided for projects worth $1.5 billion ($2.1 billion in today’s dollars). As of August 31, 1998, Quebec had received 99.3% of the funds allocated to it. Investment slowed as the joint program wound down in the late 1990s. Without its assistance, municipalities could not maintain the previous pace of investment, especially since property values rose only slowly from 1993 to 2000.

One consequence of the end of the joint program was that municipal investment did not match depreciation from 1998 to 2003. The capital stock of local, municipal and regional governments shrank in real terms.

To stimulate the economy in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007, Ottawa launched a new federal-provincial shared cost program to encourage municipal infrastructure investment. The Urba article reports that Quebec municipalities have responded by investing almost $4 billion in infrastructure renewal since 2010. When the exceptional measures of this Economic Action Plan come to an end, the pace of investment is likely to slow, and with it the rate of increase in municipal debt. That said, it must be recognized that despite the progress made under the investment program since 2007, much work remains to be done on municipal roads, sewer systems and water mains.

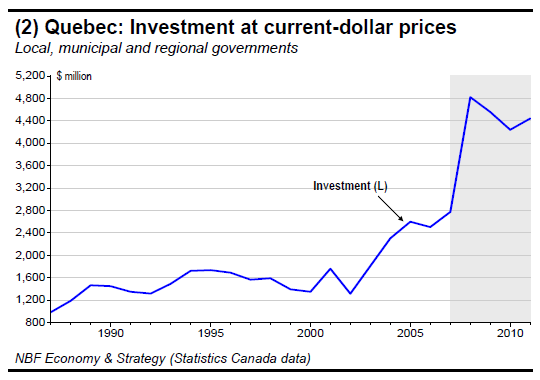

A plot of constant-dollar values has the advantage of bringing out cyclical swings in investment. However, the bills are paid in current dollars. Chart 2 highlights the explosion of capital spending in current dollars by local, municipal and regional governments since 2007. It is not hard to see why municipal debt increased almost 20% from 2007 to 2010.

Financial Position

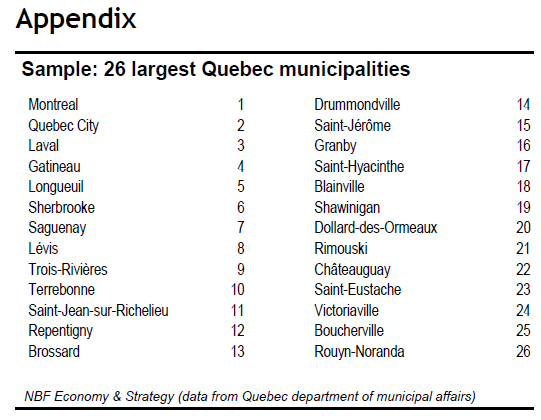

For all Quebec municipalities taken together, property taxes accounted for 55.2% of total revenues in 2010. However, among the 26 most populous municipalities (see Appendix), accounting for 60% of Quebec’s population, the percentage ranged from 36.6% to 82.2%. Thus it is hazardous to draw conclusions about the financial position of municipalities on the basis of provincial aggregate financial ratios. An exhaustive analysis of the financial position of a given municipality must consider not only changes in its financial ratios but also its demographic trends and changes in its economic structure and that of its region. Such an analysis is beyond the limits of this overview. However, there are key ratios that can serve as trip wires. Since municipal indebtedness has accelerated since 2007, we will focus our survey on changes in these ratios since then.

Since property tax revenues and payments by the federal and Quebec governments in lieu of taxes are based on property values, a municipality’s standardized property value – its property-tax base – is an indicator of its option room for meeting its obligations.

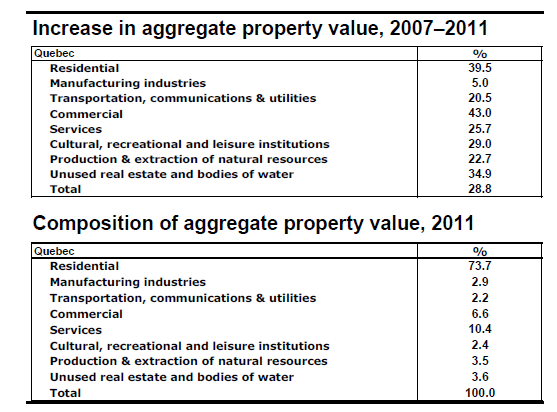

As the table above shows, residential real estate accounted for more than 70% of the total property value of Quebec municipalities in 2011, and the value of residential properties had increased 39.5% since 2007. This increase is in marked contrast to that of the period from 1993 to 2000, which according to the Conference Board of Canada averaged 0.36% annually.

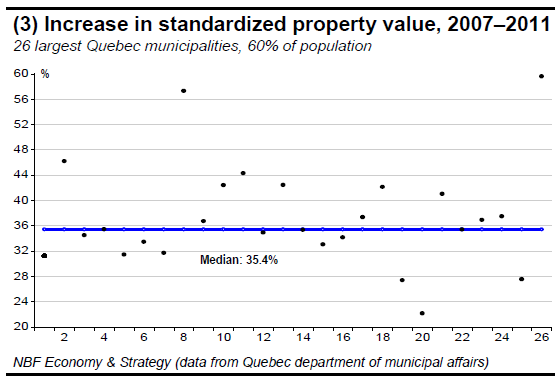

As chart 3 illustrates, the standardized property values of Quebec’s 26 largest municipalities grew robustly over the four years 2007-11. The median increase was 35.4%. For three municipalities it was less than 30%. The smallest increase was 22.1%

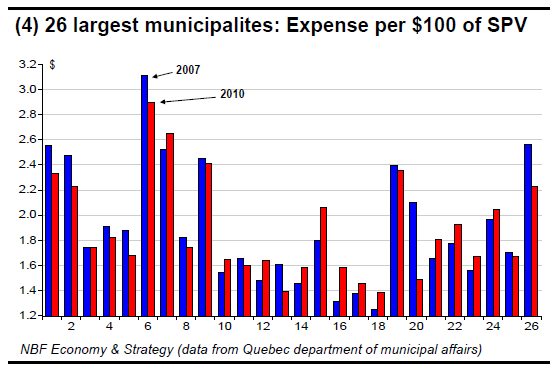

One might expect that such a steep increase in the tax base would increase the fiscal option room of these municipalities. However, changes in net expense per $100 of standardized property value (SPV) show a much more complicated reality. From 2007 to 2010, net expense per $100 of SPV increased in 11 of the 26 municipalities. On the other hand, the increases were modest, and were concentrated in municipalities whose ratios were relatively low in 2007. This observation tends to corroborate the view that municipalities took advantage of the federal Economic Action Plan and the Quebec government1 contribution to improve their citizens’ environment and add to their capital stock.

Municipal financing based on property taxation has long been open to criticism in many respects. In some cases, property taxation is ill-adapted to municipal responsibilities. If poorly weighted, it can favour urban sprawl, which raises operating costs. Apart from the regressive aspect, it is not obvious that a citizen’s ability to pay will vary with the value of his or her property.

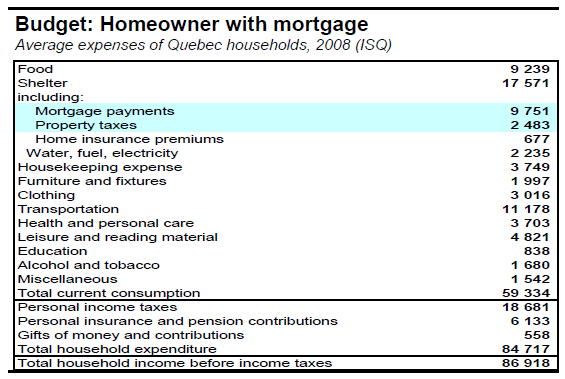

From 2007 to 2010, as can well be imagined, average household income before taxes increased less than property values, which were spurred by low interest rates. In 2008 the average Quebec homeowner household with a mortgage paid 36% of its income in mortgage payments, property taxes and personal income taxes. Thus a municipality’s option room needs to be measured not only by net expense per $100 of SPV but also by expense per capita.

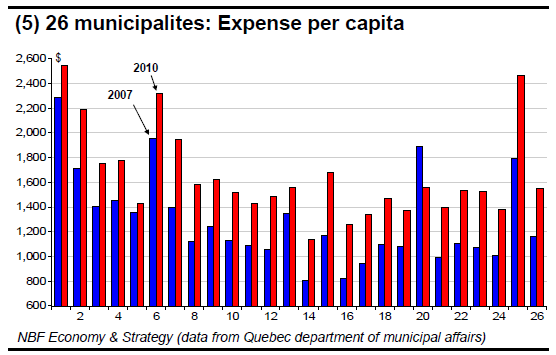

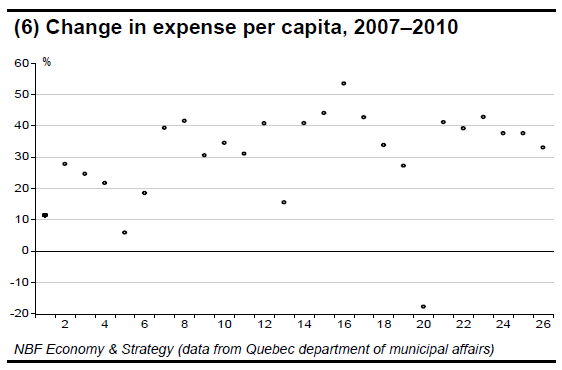

By this measure the situation deteriorated from 2007 to 2010. Net expense per capita declined in only one of the 26 largest municipalities. A rate of inflation higher than the rate of population growth would of course tend to push this ratio up over time, but expense per capita rose a median 34.2% from 2007 to 2010 while the consumer price index rose only 4.9%.

Do these indicators suggest that municipalities are at risk of falling into dire financial straits?

Though municipalities are expected to deliver a portfolio of services to their citizens and to maintain the serviceability of infrastructure under their responsibility, they can always reduce services or adjust maintenance programs if necessary. There is one expenditure, however, that leaves no room for adjustment: debt service. The greater the proportion of debt service in a municipality’s spending, the lesser its budgetary flexibility. This is why debt-related ratios draw particular scrutiny.

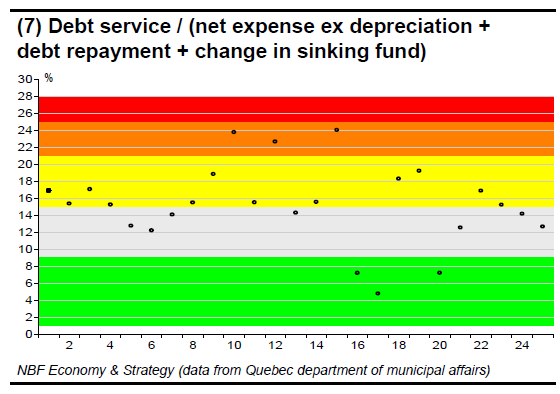

The indicator of interest for budgetary flexibility is the ratio of debt service to expense, as defined in chart 7. A ratio below 9% leaves ample room to adjust a budget in the event of an economic downturn or a spike in interest rates. Between 15% and 21% the situation remains acceptable. A ratio above 25% means investors need to keep close tabs on a municipality’s position. The latest data available show none of the selected municipalities in our sample in this position. However, three were close.

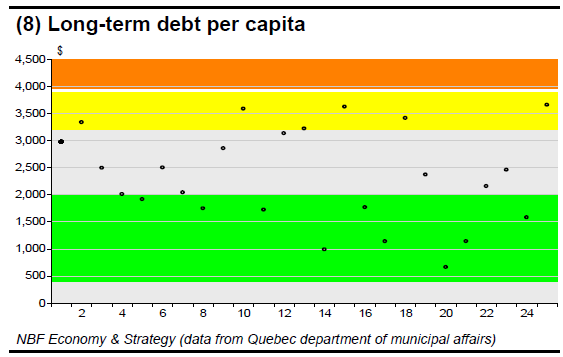

Another measure of financial health used by rating agencies is long-term debt per capita. Given the average annual income of Quebec households, we think that as a general rule a debt per capita between $3,200 and $3,900 (the yellow band in chart 8) is acceptable. Beyond this limit, investors need to look more closely at a municipality’s position. Debt per capita in the green band of chart 8, less than $2,000, would not normally be a source of vulnerability for a municipality. Debt per capita between $2,000 and $3,200 should leave a municipality well able to meet its financial obligations. It is important to note that by this measure, all of the selected municipalities in our sample fall in the range from acceptable to excellent.

Thus despite the steep growth of municipal debt, the financial flexibility of these municipalities seems in general more than acceptable.

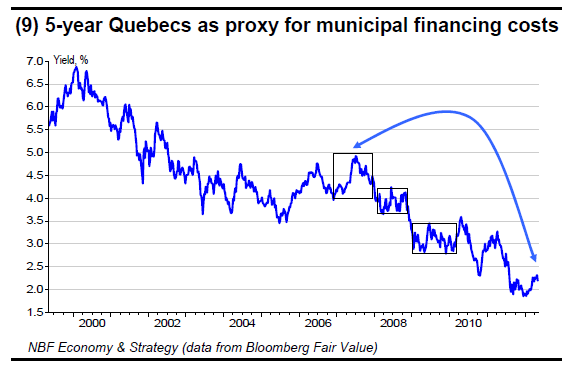

That said, what would happen if interest rates rose to the levels prevailing before the last recession?

It should be kept in mind that the total impact would not be immediate, since only a portion of long-term debt requires refinancing in a given year. Since municipalities typically concentrate their borrowing in 5-year maturities, much of the borrowing of 2009 and 2010 will not require refinancing until 2014 and 2015. Much of the borrowing of 2007 will come due this year, but current interest rates suggest that it will be refinanced at rates substantially lower than those of 2007. And finally, if 5-year rates were to rise 1.5 points over the next 18 months, the borrowing of 2008 would be rolled over at rates quite similar to those of 2008. In short, the current rate structure and the experience of the last 10 years suggest that the situation is under control.

In summary, neither the rate at which Quebec municipalities increased their expense per capita nor the rate at which they took on debt between 2007 and 2011 is sustainable. However, it should be noted that of the aggregate Quebec municipal debt of $21.3 billion shown by preliminary statistics at March 31, 2012, $3.5 billion is subsidized by the Quebec government. In addition, it seems to us that the trends of the 2007-11 period reflect incentives put in place by the federal and Quebec governments rather than a lack of local government discipline. True, the large municipalities of Quebec vary widely in their spending on operations and maintenance (and in the state of their employee pension plan, a subject not discussed here). The challenges they face vary accordingly. However, our scan of selected financial ratios for the municipalities of our sample do not prompt us to sound an alarm. Our survey, of course, is not exhaustive and covers only selected municipalities.

Canada – In 2012Q1, GDP grew 1.9% annualized, in line with consensus expectations but well below the Bank of Canada’s estimate of 2.5%. Growth in the prior quarter was revised up one tick to 1.9% annualized. Domestic demand grew just 1.3% after expanding 1.6% annualized in 2011Q4. Domestic demand was dampened down by tepid consumption spending, which swelled a meagre 0.9% annualized, and by waning government spending (-1.7%). Business investment in machinery and equipment provided some offset (+4%). Residential construction grew 12.3%, in line with strong housing starts. Trade was a drag on GDP as higher exports were more than offset by higher imports. Inventories contributed to GDP for the first time in three quarters. The 2012Q1 GDP report was disappointing notwithstanding the upward revision to the previous quarter’s growth. The monthly data showed output in March increased a mere 0.1%. Such a soft handoff means 2012Q2 will not be stellar either and it would come as no surprise to see a third consecutive print below 2%. Looking even further down the road, the fact that the savings rate is now at its lowest since 2007 does not bode well for consumption and, in turn, for an already listless domestic demand. Moreover, while investment intentions are good according to the latest BoC business outlook survey, odds are that businesses will delay outlays on account of the uncertainty surrounding Europe. As a result, we can expect the BoC to pluck much of the hawk from its tone.

In April, the Teranet–National Bank National Composite House Price Index™ rose 5.9% year over year, down from the 6.0% print recorded in March. The 12-month change in prices varied widely across metropolitan areas: 10.1% in Toronto, 6.6% in Winnipeg, 5.9% in Hamilton, 4.9% in Montreal and Vancouver, 4.8% in Halifax, 4.2% in Ottawa-Gatineau, 3.9% in Quebec City, 1.9% in Calgary and Edmonton, and -1.8% in Victoria. On a seasonally adjusted basis, the Composite was up 0.6% month over month.

United States – In May, the U.S. labour market disappointed once again, adding just 69K jobs, well short of the 150K gain expected by consensus. The bad news was compounded by downward revisions to the two previous months, which sheared another 49K jobs. Private-sector employment rose by 82K jobs. The manufacturing sector continued to extend payrolls (+12K), albeit at a more subdued pace than before. Government continued to shed jobs with a 13K drop in payrolls. Average hourly earnings eked up 0.1%, while average hours worked per week slipped a tick to 34.4. The unemployment rate climbed a notch to 8.2% as the participation rate rose two ticks to 63.8%. Non-farm payrolls (NFP) fared poorly. Full-time employment declined by more than 1.1 million in the last two months, nearly reversing the 1.4 million jobs gained from January to March. Searching deep, the only silver lining in the report was to be found in the improved diffusion, that is, the fact that job gains were more broadly based across sectors. This reduces the chances that the U.S. labour market is on the verge of total collapse. Aggregate hours are flat-lining so far in Q2 (versus 3.9% growth in Q1), while wages are tracking at 1.2% (versus 5% growth in Q1). This suggests more softness in GDP after Q1 growth came in below 2%. The slower growth and the disappointing NFP have clearly raised the likelihood of further Fed intervention after Operation Twist expires this month.

Still in May, consumer confidence fell for a third month in a row. The Conference Board index dropped far more than expected by consensus, going from a downwardly revised 68.7 to 64.9, its lowest mark since January. Consumers were less upbeat about both the current situation and the outlook. Respondents were also slightly less upbeat about employment prospects, with a smaller percentage viewing employment as "plentiful" and the "hard to get" employment sub-index shooting up to its highest point since January. Ironically, respondents were more eager than in April to purchase autos and major appliances.

Again in May, the ISM manufacturing survey sank to 53.5 from 54.8 in April, reversing most of the previous month’s advance. Still, new orders added 1.9 points to 60.1 after gaining 3.7 the month before, while inventories slid further to 46. This should lend some support to the manufacturing sector in the coming months. However, export orders more than reversed the prior month’s gain, slumping from 59 to 53.5.

In other news, GDP in 2012Q1, initially estimated by the BEA at 2.2% annualized, was revised down to 1.9%, matching consensus expectations.

In March, the Case-Shiller composite 20-city home price index registered a 0.1% monthly increase (or +0.7% annualized in the three months to March). Prices were down 2.6% year over year, although this was an improvement over previous months (-3.5% y/y in February and -3.9% y/y in January).

Euro Area – In May, the euro zone Economic Sentiment Indicator slid from 92.9 to 90.6. This second decline in a row left the index at its lowest level in two and a half years. The breakdown by sector showed widespread weakness while the breakdown by country highlighted acute weakness in the peripheral economies and deterioration in France and Germany.

In April, the euro zone seasonally adjusted unemployment rate stood at 11.0%. The March figure was revised up from 10.9% to 11.0%. According to Eurostat, there were 1.797 million more unemployed in the euro zone than one year earlier.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

A Look At Quebec Municipal Debt

Published 06/05/2012, 08:21 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

A Look At Quebec Municipal Debt

Introduction

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.