William Dudley of the New York Fed made an important speech yesterday entitled Reflections on the Economic Outlook and the Implications for Monetary Policy that justified the Fed's decision to delay the taper. What I am puzzled at is that many of the points that he makes have been known for quite some time. In the interests of an open and transparent communication policy, why didn't the Fed tell us this before?

Dudley outlined the drags he saw in the economy. The first is the fiscal drag from sequestration. So why is that such a surprise?

However, against these improving economic fundamentals, we have two important offsets. The first offset is the unusually high degree of fiscal drag, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates at about 1¾ percent of potential GDP in 2013.1 The two most important components of this restraint are the end of the payroll tax holiday and the increase in income tax rates this past January, and, more recently, the government spending cuts resulting from budget sequestration.

The second is the rise in interest rates since the May 22 announcement that the Fed was considering a taper. This may be one of the key reasons why the Fed decided to delay.

Another new source of drag for the economy is the sharp rise in long-term interest rates, especially residential mortgage rates—that has occurred since May. So far we don’t have much hard data on how this is affecting the housing sector. But data through mid-September generally indicate that the rise in rates has cut into the upward momentum of the housing sector.

How well "repaired" is the household balance sheet?

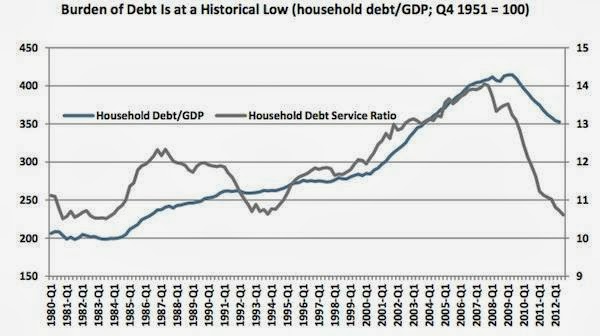

The chart below (via John Mauldin) shows how the household sector has repaired its balance sheet since the Lehman Crisis. The grey line shows the household debt ratio, which has declined to levels not seen since the early 1990's. That good news, right?

Not so fast. The blue line shows the household debt to GDP ratio, which has fallen from its peak but remains at highly elevated levels. The way I interpret this chart is that the fall in debt service burden was largely a function in the decline in interest rates. If rates were to "normalize", then the household balance sheet may not be as "repaired" as many analysts may think.

Dudley went on to reiterate his concerns about the interest sensitive nature of consumer spending [emphasis added]:

Turning first to consumer spending, such spending has remained fairly subdued outside of interest rate-sensitive consumer durables. In July, for example, real personal consumption expenditures were flat, and it is unlikely that third quarter consumption growth will be much above a 2 percent annual rate.

He went on to state his concerns about the sustainability of consumer spending growth:

Moreover, the drivers of consumer spending do not look particularly supportive. In particular, real disposable income growth has grown at less than a 1 percent annual pace since March. Furthermore, the recent data do not yet clearly indicate a firming in the income growth rate, or the two important components of labor income growth—hours and compensation.

The conundrum for consumers is a simple one: if consumer spending growth is to exceed 2 percent annualized on a sustained basis at a time when real disposable income growth is below 2 percent then this would require the household saving rate to decline persistently. But there is little reason to expect such a decline given that the current saving rate is at a level consistent with current level of household wealth relative to income.

He concluded that you can't expect the household sector to continue to dig into their savings in order to spend:

Moreover, the drivers of consumer spending do not look particularly supportive. In particular, real disposable income growth has grown at less than a 1 percent annual pace since March. Furthermore, the recent data do not yet clearly indicate a firming in the income growth rate, or the two important components of labor income growth—hours and compensation.

The conundrum for consumers is a simple one: if consumer spending growth is to exceed 2 percent annualized on a sustained basis at a time when real disposable income growth is below 2 percent then this would require the household saving rate to decline persistently. But there is little reason to expect such a decline given that the current saving rate is at a level consistent with current level of household wealth relative to income.

Implicitly, job growth is the ultimate driver of consumer spending growth - and the job market remains weak. Dudley confirmed this view when he explained the reasoning behind his own vote not to taper [emphasis added]:

Several questions have emerged following the meeting. Most noteworthy was—given that market expectations were skewed towards anticipating the beginning of a taper at this meeting—why the Committee did not begin to reduce the pace of asset purchases. Although I can’t speak for the Committee, I can provide some reasons for my own decision.

To begin to taper, I have two tests that must be passed: (1) evidence that the labor market has shown improvement, and (2) information about the economy’s forward momentum that makes me confident that labor market improvement will continue in the future. So far, I think we have made progress with respect to these metrics, but have not yet achieved success.

With respect to the first metric, we have seen labor market improvement since the program began last September. Over this time period, the unemployment rate has declined to 7.3 percent from 8.1 percent.4 However, at the same time, this decline in the unemployment rate overstates the degree of improvement. Other metrics of labor market conditions, such as the hiring, job-openings, job-finding rate, quits rate and the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio, collectively indicate a much more modest improvement in labor market conditions compared to that suggested by the decline in the unemployment rate. In particular, it is still hard for those who are unemployed to find jobs. Currently, there are three unemployed workers per job opening, as opposed to an average of two during the period from 2003 to 2007.

Other analysts, such as former Fed vice-chair Don Kohn, have pointed out concerns over the impending fight over the debt-ceiling:

With respect to the second metric—confidence that the economic recovery is strong enough to generate sustained labor market improvement—I don’t think we have yet passed that test. The economy has not picked up forward momentum and a 2 percent growth rate—even if sustained—might not be sufficient to generate further improvement in labor market conditions. Moreover, fiscal uncertainties loom very large right now as Congress considers the issues of funding the government and raising the debt limit ceiling. Assuming no change in my assessment of the efficacy and costs associated with the purchase program, I’d like to see economic news that makes me more confident that we will see continued improvement in the labor market. Then I would feel comfortable that the time had come to cut the pace of asset purchases.

What's new here?

I think that this was an important speech from a key Fed governor explaining the decision to delay the taper. William Dudley is not far from the mainstream thinking at the FOMC, but I still believe that much of the reasoning behind the decision was not a surprise. Here are his key reasons:

- Consumer spending is interest sensitive because household debt levels are still on the high side. As rates have started to rise, it could restrain spending, which is an engine of growth. (No surprise here.)

- The improvement in unemployment rate, a key Fed metric, masks many weaknesses in the job market. In particular, the participation rate has been falling more than expected. (No surprise either, the Fed has been talking about the fall in participation rate for some time.)

- The fiscal drag from sequestration is restraining growth. (Hello! The Fed would have known about this before the May 22 announcement.)

- The uncertainty over the debt-ceiling fight is creating uncertainty. (Is the Fed that timid?)

Unless the FOMC is truly freaked out about the possible effects of the debt-ceiling debate, I don't see anything very new here. The other factors are already well known, but between May 22 and September 19, we had Bernanke and a parade of Fed governors telling us that, while everything is "data dependent", they were on track to taper by the end of the year if the economy continues on the current trajectory.

So what changed? Did they freak out over a debt-ceiling impasse? They knew that interest rates were backing up, so that was not surprise.

IMHO, the FOMC's September surprise decision was a failure of the Fed's communication policy.

Cam Hui is a portfolio manager at Qwest Investment Fund Management Ltd. (“Qwest”). The opinions and any recommendations expressed in the blog are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions and recommendations of Qwest. Qwest reviews Mr. Hui’s blog to ensure it is connected with Mr. Hui’s obligation to deal fairly, honestly and in good faith with the blog’s readers.”

None of the information or opinions expressed in this blog constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or other instrument. Nothing in this blog constitutes investment advice and any recommendations that may be contained herein have not been based upon a consideration of the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient. Any purchase or sale activity in any securities or other instrument should be based upon your own analysis and conclusions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Either Qwest or I may hold or control long or short positions in the securities or instruments mentioned.