These headwinds will persist for the next decade or two.

The stock market is rallying hard after a brutal sell-off--not an uncommon occurrence. As we savor our winnings in the ship's first-class casino, it's not a bad idea to step out onto the deck and gauge the weather.

There are headwinds. Not zephyrs, not gusts, just steady, strong headwinds.

1. Presidents Trump and Xi view each other as an existential challenge to the future prosperity of the nations they lead. Neither can afford to lose face by caving in, and each has a global strategy with no middle ground.

2. Global trade/capital flows are all over the map. Uncertainty is the word of the moment, but perhaps the more prescient description is unpredictability: if enterprises have no visibility on the future costs of trade, commodities, labor and capital, they have little choice but to avoid big bets until visibility is restored.

3. The American consumer is tapped out. Credit card charge-offs are rising, auto loan defaults are rising, and air travel is faltering--there are many sources of evidence that consumers--especially the top 20% households whose spending has propped up the economy--have reached financial and perhaps psychological limits.

4. The Reverse Wealth Effect is kicking in as stocks and other assets roll over into volatility and potential trend changes into declines rather than advances. The top 10% who own the majority of income-producing assets and risk assets are seeing $10 trillion of losses followed by recoveries of $5 trillion. Swings of such magnitude do not support confidence in the stability of current valuations or offer visibility on the odds of future capital gains.

Just as enterprises must respond to poor visibility by reducing risk, households respond to increasing volatility and unpredictability by reducing borrowing and spending. Stable gains in asset valuations fuel the Wealth Effect, encouraging consumers to borrow and spend more because their wealth has increased. The Reverse Wealth Effect triggered by losses, volatility and low visibility encourages reducing risk, borrowing and spending.

5. There will be no "save" by the Federal Reserve or massive new Federal fiscal largesse. Tariffs and reshoring manufacturing are inflationary, so the Fed no longer has the freedom to create a few trillion dollars out of thin air to juice risk assets. The federal government's borrowing-and-spending spree threatens the integrity of the nation's currency and economy, so the unlimited checkbook has been put in the drawer.

6. The two decades of deflation generated by China have ended. Central banks could play in the Zero-Interest Rate Policy sandbox because inflationary forces were all offset by the sustained deflationary forces of China's export machine and credit expansion. Now, every economy, including China's, faces inflationary tides from a number of sources.

7. The sums required to rebuild America's industrial base will pinch speculative borrowing and consumer spending. Now that both the Fed and the federal government are restrained from borrowing and blowing additional trillions, private capital will have to be enticed into long-term investments in Treasury bonds and reshoring. The ways to incentivize long-term investing rather than consumption and speculation are recession and deflating asset bubbles. Both re-set expectations, risk appetites and incentives.

Everyone with direct experience of manufacturing and supply chain networks is telling us that reshoring will be a costly, long-term project, requiring the rebuilding of the entire ecosystem that's been lost to hyper-globalization's offshoring and hyper-financialization's predation.

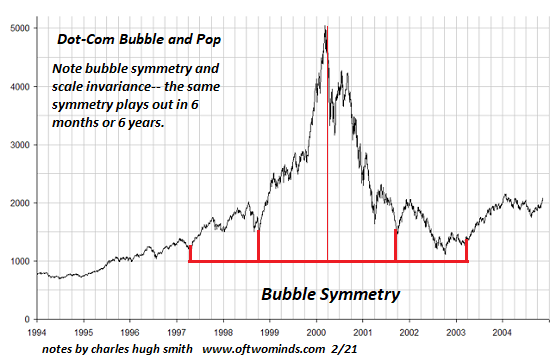

Note that all credit-driven asset bubbles pop. Yes, the market is rigged, but that doesn't mean it always goes up or that it's easy to catch the declines. The dot-com bubble lost 80% of its peak valuation despite assurances that it was "impossible."

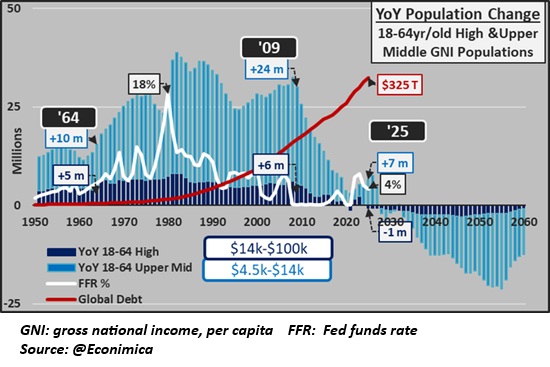

8. Demographics are not supportive of risk-asset expansion. Courtesy of @Econimica, consider this chart of the year-over-year change in high and high-middle-income populations globally. The change is now negative--fewer folks are entering these categories. In response, global debt has soared, in effect offsetting the decline of consumer demographics with borrowed money.

As the global Boomer population retires and needs at-home or institutional care, they will sell their assets to fund these soaring expenses: stocks, bonds, real estate--all will go on the auction block to raise cash.

The older cohort of investors is also more risk-averse, as they know they don't have a decade or two to recover from a catastrophic decline in their assets' valuations.

None of these dynamics can be reversed. These headwinds will persist for the next decade or two.