Last week my friend John Mauldin, chairman of Mauldin Economics, released a special Brexit edition of his popular investments newsletter Outside the Box. In it he shared a post written by geopolitical strategist George Friedman that describes a recent meeting among six foreign ministers representing the European Union’s founding member states:

Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. The topic of discussion was the possible causes and implications of the U.K.’s decision to leave the EU.

What George finds extraordinary is that, in their follow-up statement, the ministers appear to capitulate, admitting they “recognize different levels of ambition amongst Member States when it comes to the project of European integration.”

As George puts it, this is their way of acknowledging—finally?—the impossible task of enforcing uniformity across the European continent, home to many different peoples and cultures, all with different goals and aspirations.

If nothing else, this alone should be seen as a positive consequence of Brexit. It’s too early to tell what direction the EU will take post-Brexit, or whether any material policy changes will be made, but it seems as if the cries of resentment and frustration that have risen up from England and Wales (and, to a lesser extent, Scotland and Northern Ireland) have not fallen on deaf ears.

This is precisely what I’ve been writing about the last few weeks. If you’ve been following the mainstream media’s coverage of Brexit, you might think it’s little more than a reactionary, anti-immigrant groundswell. Don’t get me wrong—immigration is certainly part of it.

Trying to integrate 50,000 people a year into the country’s national health care and school system has pushed the bandwidth of the British economy.

But the U.K.’s grievances—some of which I discussed in previous commentaries—are much more varied than that. And following the historic referendum, EU bureaucrats seem to be taking the gripes seriously, which we can count as a win not just for the U.K. but other member states as well.

Four More Brexit Winners

1. Gold Investors

The day after the referendum, gold jumped nearly 5 percent and since then has held above $1,300 an ounce, helping to achieve its best first half of the year since 1974. The yellow metal, which has historically been sought by investors during times of political and economic uncertainty, is also strengthening now that a U.S. interest-rate hike seems less and less likely post-Brexit.

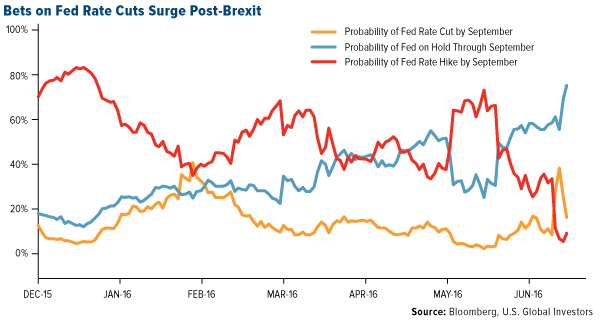

Markets, in fact, seem to have completely shed any belief that the Federal Reserve will raise rates this year. Bets that rates will be cut by September spiked before retreating, while bets that they would be left untouched surged 48.6 percent.

This bodes well for gold, which has traditionally shared an inverse relationship with interest rates. When savings account rates and yields on government bonds are low, gold suddenly becomes much more attractive to hold as a store of value.

This is especially true in countries where rates are negative. The yield on the German 10-Year Bund recently fell below zero and the Swiss 30-Year government bond yield turned negative, in effect charging investors for the privilege of holding their cash.

But American investors aren’t immune. Last Friday, the yield on the 10-Year Treasury fell to as low as 1.385 percent, an all-time record.

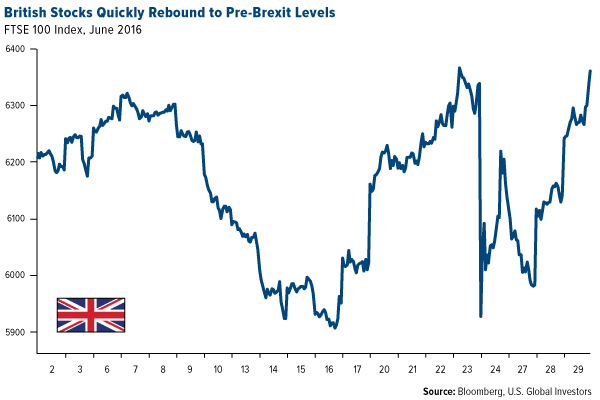

Across the pond, British rates are likely to be slashed this summer, according to Bank of England Governor Mark Carney. In response, Britain’s FTSE 100 Index roared up to a 10-month high, erasing all Brexit-inflicted losses.

2. U.S. Homeowners

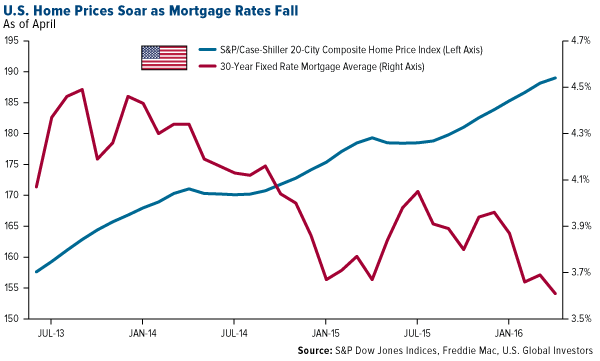

The promise of continued low rates in Brexit’s wake could be good news for U.S. homeowners, both current and potential. For the week ended June 24, the mortgage rate on a 30-year home loan fell to 3.75 percent, its lowest level since May 2013, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Some analysts are even forecasting mortgage rates -- which tend to track 10-year Treasury yields -- to sink to record lows in the coming weeks. This move is expected to spur a wave of new loan applications and refinancing as borrowers rush to lock in historically low rates.

Home prices in the U.S., meanwhile, continue to improve after the financial crisis. Prices advanced 5 percent year-over-year in April, according to new data from the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Prices Indices. The 20-City Composite Index, in fact, is back up to its winter 2007 level.

3. British Luxury Goods Makers

In the immediate aftermath of the U.K. referendum, Donald Trump suggested the pound’s dramatic decline could encourage more foreign tourists to visit Turnberry, Scotland, where he owns a luxury golf resort. Many in the media criticized him for the comment, arguing he seems to care only about how he might profit from Brexit. But the thing is, he’s right.

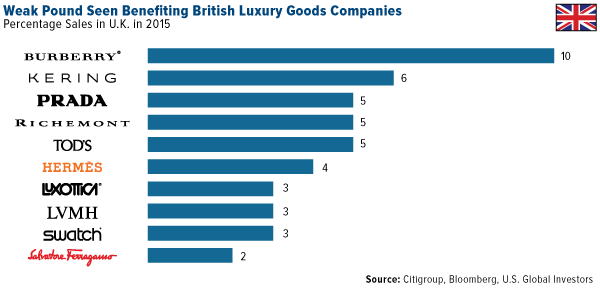

Because of the drop in the pound, which sent it to levels not seen in more than 30 years, U.S. and Chinese interest in travel to Britain has already seen a huge spike. This could be a potential windfall for Britain’s luxury goods industry, which posted sales averaging nearly $1 billion in 2014, according to advisory firm Deloitte. Clothing designer Burberry (LON:BRBY), Britain’s largest luxury company, could end up being a beneficiary, along with many other major European brands found in the U.K.

I’ve mentioned before how Chinese tourists spend more than any other country’s. Now, a March report by the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) found that in 2015, outbound Chinese travelers shelled out a massive $215 billion overseas, representing an increase of 53 percent from the previous year. A weakened pound should only intensify demand even more.

4. British Taxpayers

According to the Daily Express, about 10,000 Brussels-based bureaucrats earn more than -- and in many cases, more than twice as much as -- U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron, who has a gross annual salary of 142,500 pounds. What’s more, they pay the euro-equivalent of 50,000 pounds less per year than Cameron does in taxes. And before the 2015 Christmas break, these Eurocrats, who all enjoy a final salary pensions, just gave themselves a 2.4 percent raise.

The British referendum was in large part a rejection of this brand of elitism. Similar to what many Americans feel today, taxpayers in the U.K. are fed up with seeing their money leave the British shores only to line the pockets of unelected officials, with little to show for it in return.

The two-year transition period that follows will likely present many challenges, but in the long run, an independent Britain will be able to set its own immigration policies, impose its own rules and regulations, negotiate the terms of its own trade agreements and much more.

Disclosure: All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product. Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication.