Summary

- A majority of the Fed governors argued for a 25 basis point cut at the latest meeting.

- There were two dissenting groups: those that argued for no change and those who wanted larger (50 basis point) cuts.

- A majority of the Fed sees international weakness and softer US as supporting a modest rate cut.

The purpose of the Turning Points Newsletter is to look at the long-leading, leading, and coincidental data to determine if the economic trajectory has changed from expansion to contraction - to see if the economy has reached a "Turning Point."

My recession probability in the next 6-12 months is 20%. As noted in the Fed Meeting Minutes, there is sufficiently weak international and domestic data to support a preemptive cut for risk management purposes. This simply another way of saying a recession is at least a modest possibility at this point.

At the last Federal Reserve Meeting, there was a very noticeable split among the Fed governors regarding the current condition of the US economy. The consensus argued for a rate cut largely as a prospective insurance policy due to international and domestic softness. But there were two dissents from that opinion: one group argued things were fine, implying that the Fed didn't need to act, while another group argued things were worse, meaning the Fed needed to cut 50 basis points.

Let's start with two indicators that comprise the Fed's dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability.

Here's how the Fed described the labor market (emphasis added):

Total nonfarm payroll employment expanded at a solid pace in July and August, although at a slower rate than in the first half of the year. ... The unemployment rate remained at 3.7 percent through August, and both the labor force participation rate and the employment-to-population ratio moved up. ... The average share of workers employed part time for economic reasons in July and August continued to be below its level in late 2007. Both the rate of private-sector job openings and the rate of quits moved roughly sideways in June and July and were still at relatively high levels; the four-week moving average of initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits through early September was near historically low levels. Total labor compensation per hour in the business sector increased 4.4 percent over the four quarters ending in the second quarter, a faster rate than a year earlier. Average hourly earnings for all employees rose 3.2 percent over the 12 months ending in August, the same pace as a year earlier.

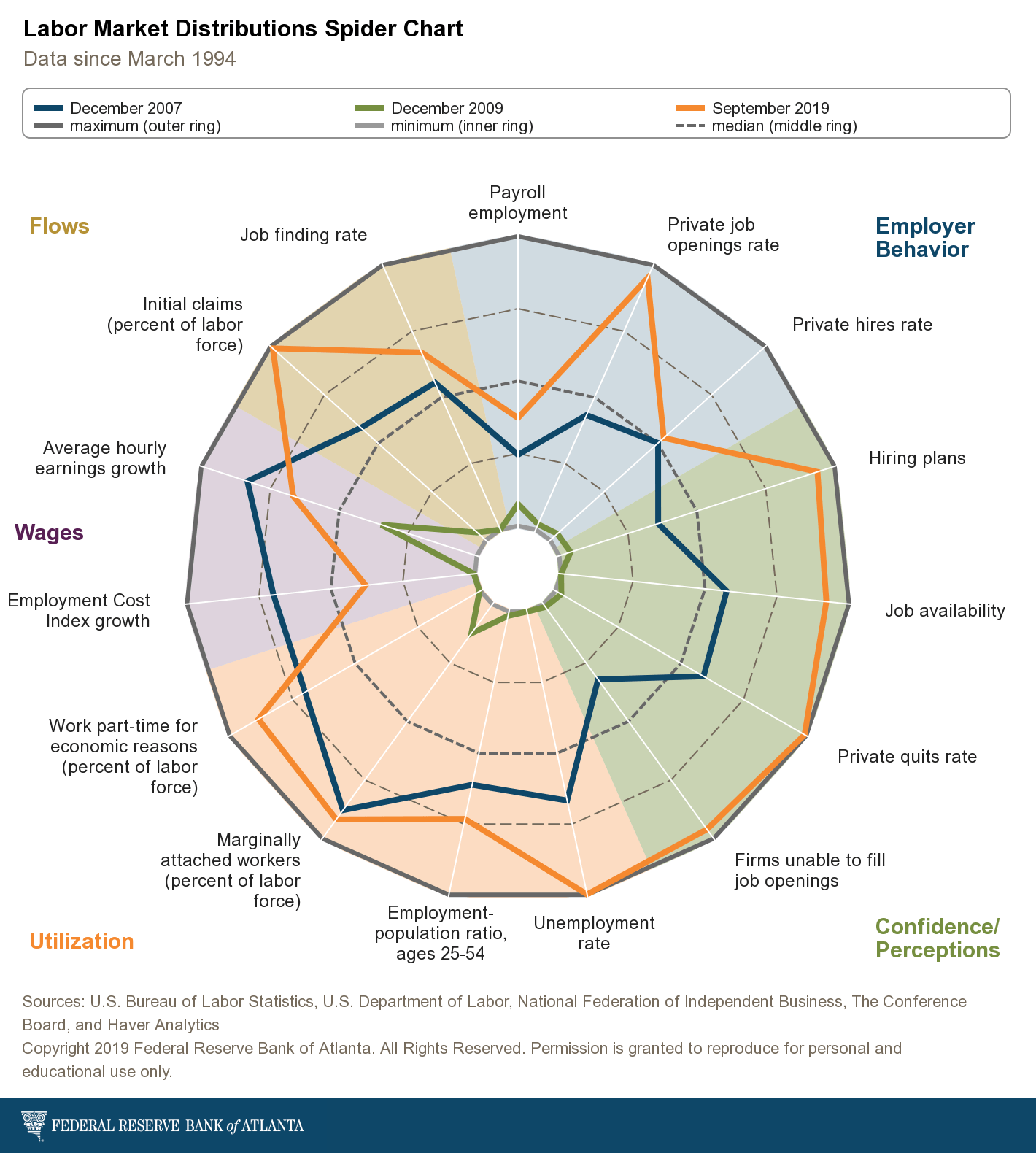

This data is best seen in the Atlanta Fed's Labor Market Spider Chart:

The gold line shows where current data is while the teal line documents the highs from the previous expansion. With the exception of wage growth, the current labor market is stronger.

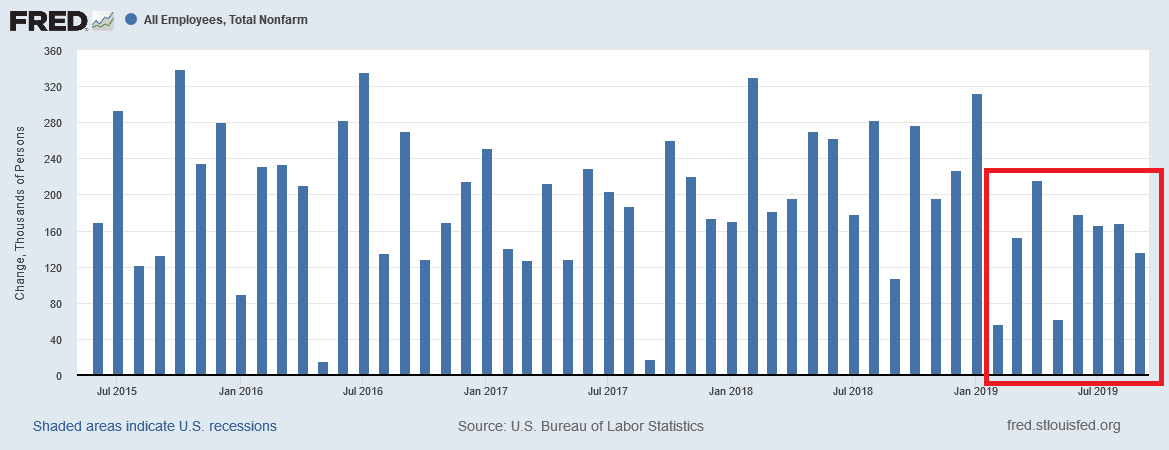

But there has been some recent labor market weakness which can be visualized in two ways. The first is the monthly total change in payroll employment:

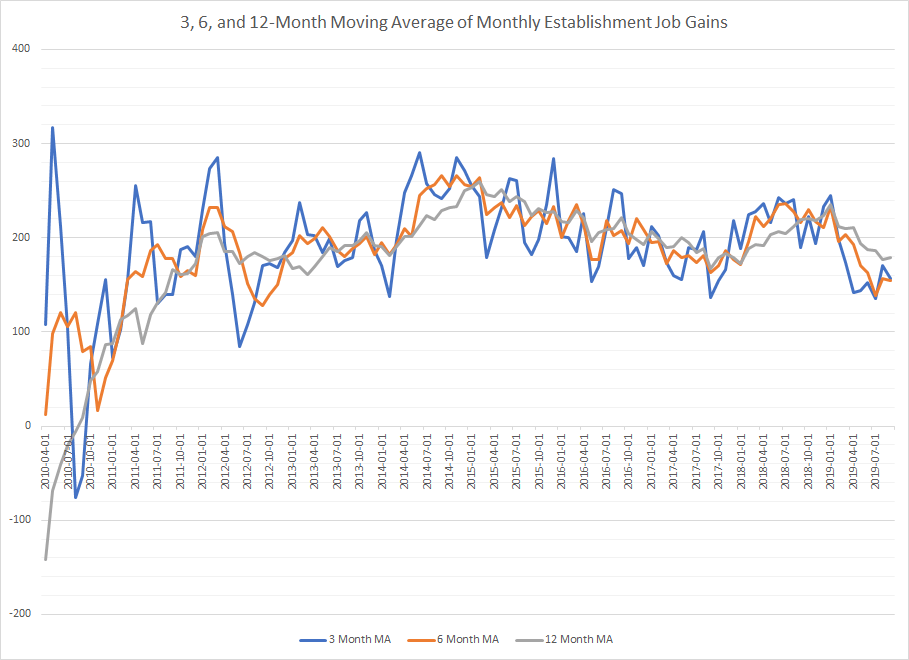

The above chart from the St. Louis Fed's system shows that the pace of monthly changes in payroll employment is lower - not fatally so, but the data is softer. The moving averages of monthly payroll growth change also show this drop:

The three-month moving average of monthly job gains (in blue) recently hit the 150,000/month level; the six-month moving average (in gold) followed the three-month average to the lower level, confirming the weakness. This isn't fatal to the expansion and could easily signal that, due to the lower unemployment rate, employers simply have fewer potential hires. But it could also signal that employers are slowing activity and therefore need fewer new workers.

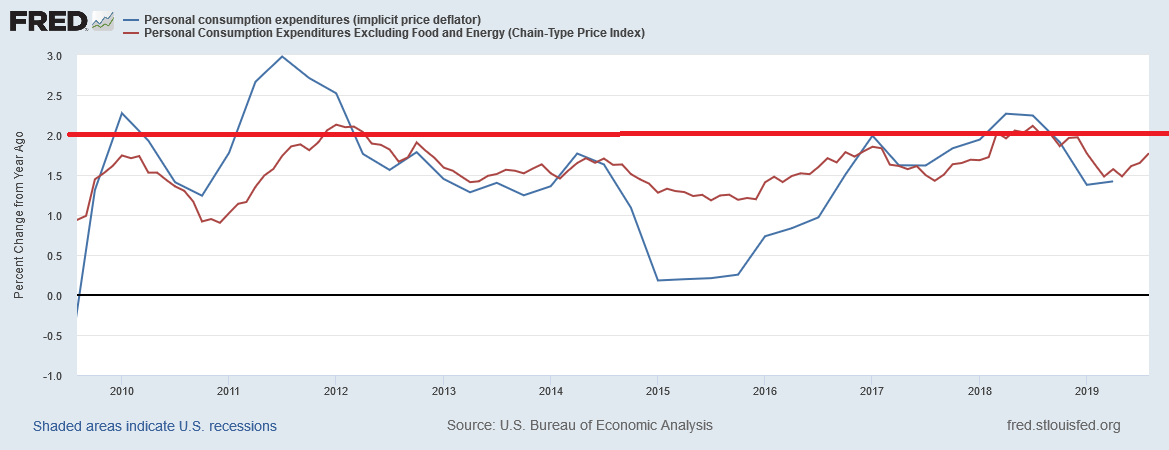

Prices have also been a key problem, as shown in the following chart:

The Fed has a 2% symmetrical inflation target - which means the Fed is comfortable with inflation being below and above that figure. However, inflation has underperformed over the last 10 years (see the red line at 2%). At first, it was understandable as unemployment was still high. But inflation remained low despite the drop in unemployment. This could mean there is still economic slack which would imply the need to lower rates.

Using just this data, we can see where Rosengren and George stand: based on the Fed's dual mandate, the Fed has done its job: unemployment is low (read: maximum employment) and inflation is contained (read: price stability). There is no reason to do anything about rates.

The consensus was dourer regarding the outlook (emphasis added):

Participants favoring a modest adjustment to the stance of monetary policy at this juncture cited other risks to the economic outlook that further underscored the case for such a move. As their discussion of risks had highlighted, downside risks had become more pronounced since July: Trade uncertainty had increased, prospects for global growth had become more fragile, and various intermeeting developments had intensified geopolitical risks. Against this background, risk-management considerations implied that it would be prudent for the Committee to adopt a somewhat more accommodative stance of policy.

This group went beyond the Fed's dual mandate, incorporating largely international data. This is borne out in Markit PMI data - especially EU, Japanese, and UK manufacturing numbers from the last 3-6 months along with GDP numbers from Germany, Japan, and the UK. The last two ISM Manufacturing reports for the US have also shown a contraction, adding further credence to this analysis.

And finally, there is the segment arguing for a 50 basis point cut (emphasis added):

A couple of participants indicated their preference for a 50 basis point cut in the federal funds rate at this meeting. These participants suggested that a larger policy move would help reduce the risk of an economic downturn and would more appropriately recognize important recent developments, such as slowing job gains, weakening investment, and continued low values of market-based measures of inflation compensation.

This group is using inflation as a way to measure economic slack. And to them, the continued weak inflation data indicates there is sufficient economic capacity to warrant a 50 basis point cut.

Central to the majority's opinion (those that want a 25 basis point cut and those arguing for a 50 basis point cut) is the possibility of international weakness being transmitted into the US economy. To some extent, this is already happening: business investment is weaker, manufacturing is contracting, and hiring has slowed.

This majority opinion supports a roughly 20% recession probability in the next 6-12 months. The combination of weak international data and softer US numbers combined with the inverted yield curve are sufficient justification for this analysis.