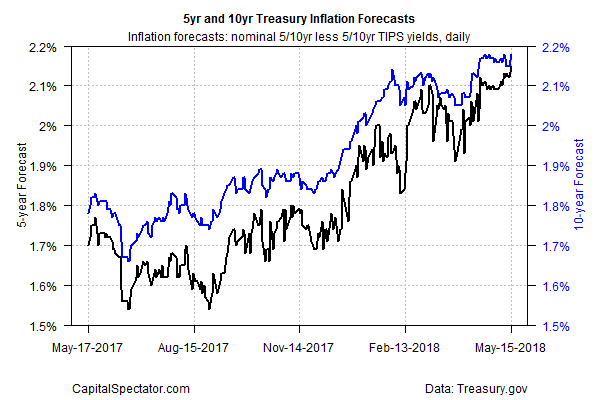

The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield edged up to 3.08% on Tuesday (May 15), marking a new seven-year high, based on daily data published by Treasury.gov. The implied inflation forecast via Treasuries continued to advance as well, signaling that the market is pricing in firmer pricing pressure in the months ahead.

Notably, the yield spread between the nominal 5-year Treasury less its inflation-indexed counterpart ticked up to 2.15%, the highest since 2013. The rise suggests that the crowd anticipates that the official inflation indexes will continue to trend higher – a development that would likely reaffirm and perhaps accelerate the Fed’s current program of tightening monetary policy.

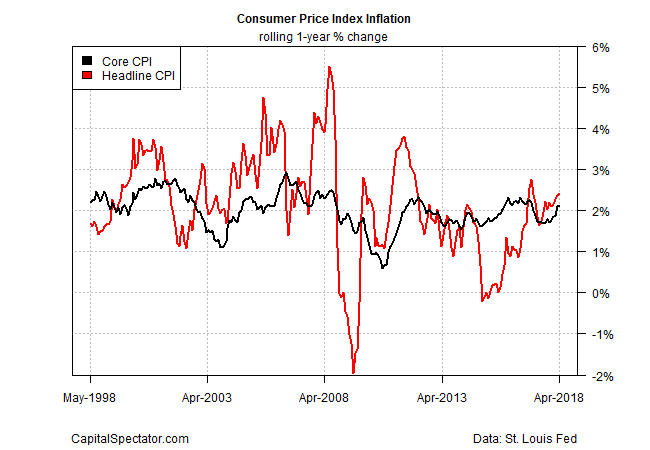

The April report on consumer price index (CPI) confirms that pricing momentum is heating up, albeit following a period of subdued inflation. In a sign of the times the CPI’s headline and core readings simultaneously posted year-over-year increases above 2% — the Fed’s inflation target – for a second month. That’s the first time that headline and core indexes have been that high in more than a year.

For the moment, a mildly hotter level of inflation isn’t worrisome, in part because the upswing coincides with expectations for stronger economic growth. Several estimates of US GDP growth for the second quarter are projecting a rebound after a subdued gain in Q1. Yesterday’s April data on retail spending offers support for thinking positively as consumer spending increased for a second month in a row – the first back-to-back set of gains since last November.

An sharp acceleration in inflation from current levels, or a downshift in economic growth, would be problematic for assuming that a Goldilocks scenario will prevail – a healthy expansion with relatively tame inflation. To date, however, those risks are considered low-grade threats.

“This is continuing to be a quintessential Goldilocks kind of economy and Goldilocks expansion: The economy’s growing at a solid pace,” advises Nathan Sheets, chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income. “This is the kind of economy central banks dream of, not too hot, and not too cold.”

Even if the economy cooperates, the Fed may overplay its hand by raising interest rates too high, too fast and inadvertently push the economy into recession. For the moment, that scenario is unlikely – business-cycle risk remains low, based on recent data.

But the potential for policy errors can’t be fully dismissed. As several analysts have pointed out, the combination of monetary tightening and an aging expansion – the second-longest on record – raises the specter of economic history. Expansions don’t die of old age, but they have been murdered by the Fed. The great hope is that this time is different, which implies that the Fed has learned from its mistakes.

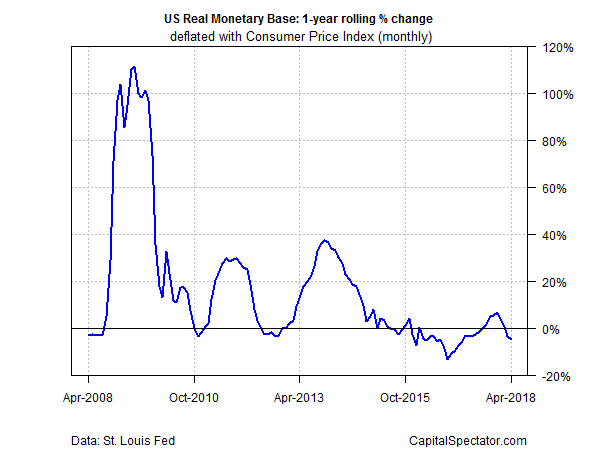

In any case, the monetary screws are tightening. Consider the year-over-year trend in real base-money supply (M0), aka high-powered money that the Fed controls. After a seven-month break of growth, real M0’s trend has turned negative again in March and April. Economic history tells us that this indicator has been a generally reliable risk factor for modeling the business cycle and deserves close attention as one of several inputs for estimating recession risk. An extended slide that pushes deeper into the red in the months ahead would surely be a warning sign.

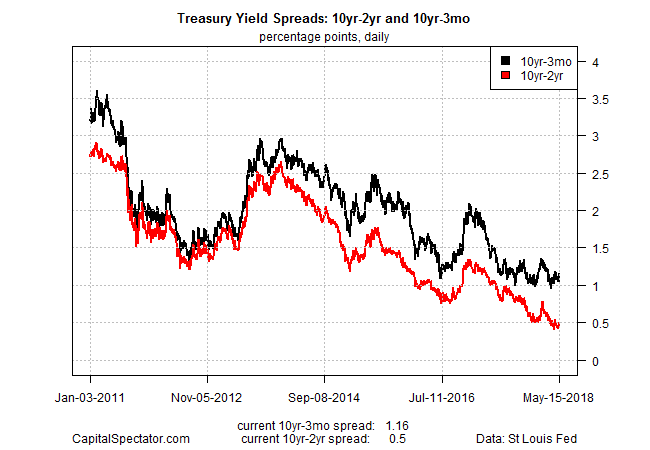

Note, too, that the Treasury yield curve – another critical variable to monitor – has been flattening recently, suggesting that Fed policy may be at risk of becoming an overt threat to the business cycle when and if short rates rise above long rates.

For now, the macro trend remains healthy and the odds are virtually nil that a recession has started, based on data published to date. Fed policy may be a gradually rising risk factor, but policy has been successful so far in navigating the narrow path of slowly raising rates without triggering a recession. It’s unclear if the central bank can successfully maintain that balancing act, but the track record to date is encouraging.

The margin for error, however, is narrowing. As rates rise, monetary policy tightens, and inflation ticks higher, the potential for trouble will increase. That alone doesn’t insure that a new recession is fate. Given the history of the Fed and the economy, however, it’s a threat that can’t be ignored.