The war in Ukraine has slowed the advance of the 10-year Treasury yield, but upside pressure is building as US inflation, already elevated, appears set to increase further in the months ahead.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve remains committed to start raising interest rates at next week’s policy meeting (Mar. 16). The market is currently pricing in a 98% probability that the central bank will lift its current 0%-0.25% target rate 25 basis points to a 0.25%-to-0.50% range. Additional hikes are predicted for the months ahead.

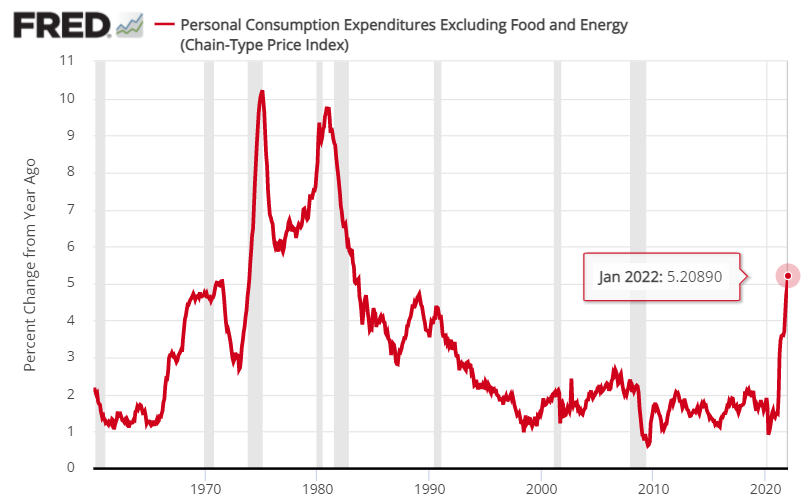

The most striking feature of monetary policy, even assuming several rate hikes, is how far behind the Fed remains relative to inflation. Core PCE inflation, which is said to be the Fed’s main measure of pricing pressure, is running at a 5.2% year-over-year rate, which is a huge 500-basis-points-plus above the current Fed funds target rate. Several weeks ago there was a reasonable forecast that inflation would ease, but such estimates went out the window in the wake of blowback unleashed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Fed finds itself between the proverbial rock and the hard place. Adjusting monetary policy to play catch-up is possible, but the risk of tipping the economy into a recession is high if rates rise quickly. Adjusting policy too slowly, on the other hand, risks letting decades of progress on managing inflation crash and burn. Finding the sweet spot between those two extremes is the goal, and one that will be devilishly difficult to navigate.

Moody’s Analytics Chief Economist, Mark Zandi, advised:

“It’s going to be very tricky. The economic plane is coming into the tarmac at a very high rate of speed, buffeted by severe crosswinds from the pandemic, with a lot of fog created by uncertainty due to geopolitical events.”

Yet the case for rapid and relatively substantial rate hikes is compelling, at least on paper. Consider the Cleveland Fed’s estimate of an appropriate Fed funds rate based on several models. The median estimate for this year’s first quarter is 3.2%, far above the current 0%-0.25% rate. And that’s before factoring in the recent changes in inflation pressure triggered by the war in Ukraine.

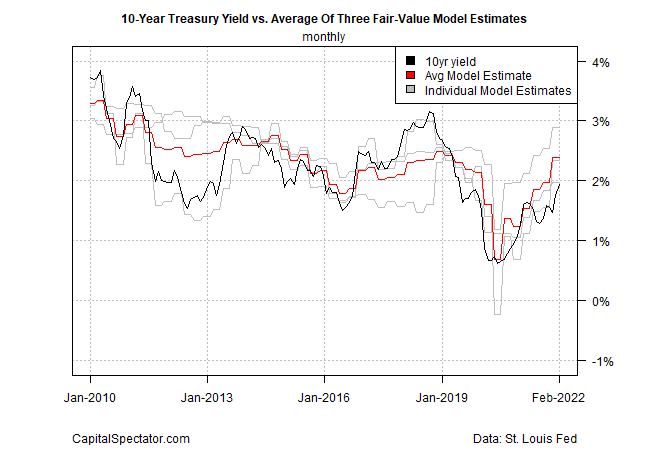

Not surprisingly, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield has been trending higher, albeit relatively modestly given the sharp upside change in inflation pressure. Absent the Ukraine war, which has revived the safe-haven trade of buying Treasuries (and pushing yields down), the 10-year rate would probably be substantially higher than the current 1.86% (Mar. 8).

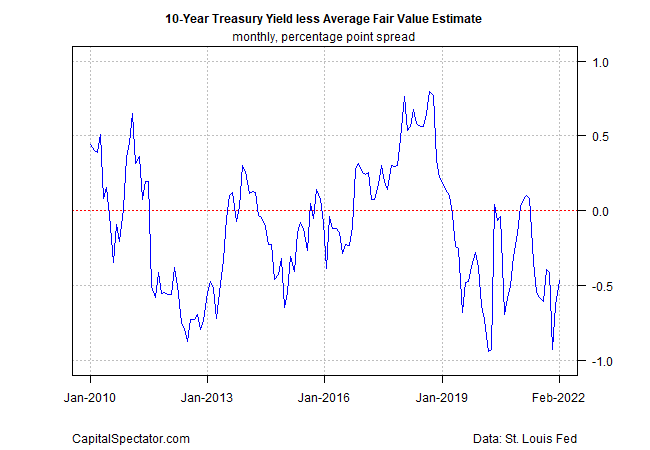

Meanwhile, the CapitalSpectator.com’s average fair-value estimate for the 10-year yield (based on three models) continues to indicate that the market rate should be moderately higher. The average fair-value estimate for the modeling is 2.40%, or nearly 50 basis points over the current market rate. Note that this estimate is based on data through February. It’s easy to assume that once the hotter inflation data that’s likely brewing for March is factored into the analysis, the fair-value estimate will rise further, perhaps sharply.

Today’s February estimate marks the ninth straight month that the market-based 10-year yield traded below our fair value estimate. In other words, an upside bias for the market rate remains intact, based on the modeling.

Meanwhile, analysts are warning that adjusting Fed policy to reflect current and future conditions is a risk factor for the economy.

“When you’re wrong in one direction and you’re painfully wrong, you’re going to have to end up with too much heavy lifting to go in the other direction.”

Says former Fed Governor Lawrence Lindsey, who estimates the odds of a recession by the end of 2023 at 50%-plus.