I have regularly written about the many shortcomings of human psychology when it comes to investing. More importantly, while the emotions of greed and fear are the predominant drivers of not only investor behavior over time, they are also attributable to the development and delivery of the financial products that Wall Street promotes.

Wall Street firms, despite what the media advertising tells you, are businesses. As a business, their job is to develop and deliver products to investors in whatever form investor appetites demand. As markets rise and fall, investors consume products and services accordingly. During strongly rising markets the demand for “risk” related products rise. Conversely, as markets fall, the demand for safety and income rises as “risk” related losses mount. Of course, Wall Street is always happy to provide those “products” to the consumers they serve.

It is from this perspective that as we see the financial markets cycle from boom to bust, we have seen a series of product and services offerings come and go in the financial marketplace. In the early 80s, we saw the rise of “portfolio insurance” which eventually gave way in the Crash of ’87.

As the bull market gained momentum in the 90s the proliferation of mutual funds exploded as Wall Street told investors that buying and holding mutual funds, and letting their “experts” manage the money, was the ONLY way to invest. As Wall Street made stars out managers like Peter Lynch and Bill Miller, the demand by individual investors grew. As Wall Street quickly figured out that it was far more lucrative to collect ongoing fees rather than a one-time trading commission, the age of the “stock broker” officially died as the rise of the asset-gathering “financial consultants” gained traction. The mutual-fund business was booming and business was brisk on Wall Street as profits surged.

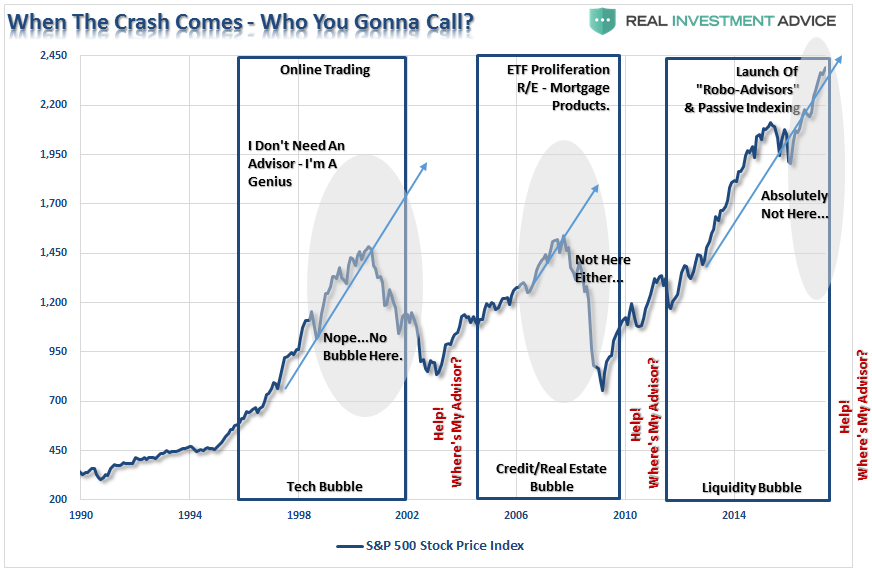

However, as the internet was developed, the next major financial innovation occurred – online trading. For the first time, Wall Street could tap directly into the masses and the “Wall Street Casino” officially opened. The marketplace for the delivery of products and services exploded, and Wall Street was happy to deliver a steady stream of new offerings to the newly minted “investing geniuses.” Online trading services like Schwab, E*Trade, and others blossomed as trading moved mainstream and “financial consultants” were deemed “hooligans” for charging fees for “advice” for something that a “trained monkey” could do on-line.

Why would anyone pay an advisor and reduce their returns when all one had to do was point-and-click their way to wealth.

Day-trading shops were set up around the country along with videos, seminars, and academies all designed to teach individuals the “art of trading their way to wealth.”

That, of course, was the late 90s and soon thereafter not much was left but broken homes and empty bank accounts. The demand for “advice” surged as individuals, desperate for hope, clung to the “words of wisdom” from the very individuals that they had chastised during the preceding bull market.

As shown in the chart below, the cycle continues to repeat itself.

After the devastating crash of dot-com bubble, individuals shunned stocks to jump into real estate. This was surely a “can’t-lose” proposition as “everyone needs a house,” right? As the demand for real estate grew, Wall Street once again responded with a litany of products from Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT’s) to private real estate investment vehicles and, of course, the infamous mortgage-backed security and derivative products.

As the liquidity fueled real estate market gained traction, the liquidity derived from low interest rates, cash-out refinancings and mortgage-ATM’s were dumped back into the financial markets. Making money was so easy – why would anyone ever pay a financial advisor a “fee” to manage their money for them. Once again, the mainstream media jumped into the fray touting low costs investing, indexing and launching a series of “investing contests.” There was once again nothing to worry about in the financial markets – valuations were reasonable due to low interest rates, “subprime was contained,” and it was the advent of Bernanke’s “Goldilocks” economy. What could possibly go wrong?

Of course, by the time that individuals figured out the party was over; Wall Street had already left without having to clean up the mess. For a second time, emotionally battered and financially crushed, individuals rushed to seek out the human contact of financial advisors. The need to commiserate, hear words of encouragement and be shown signs of hope were worth the fees. Individuals were no longer concerned with beating some index but rather how to protect what they had left.

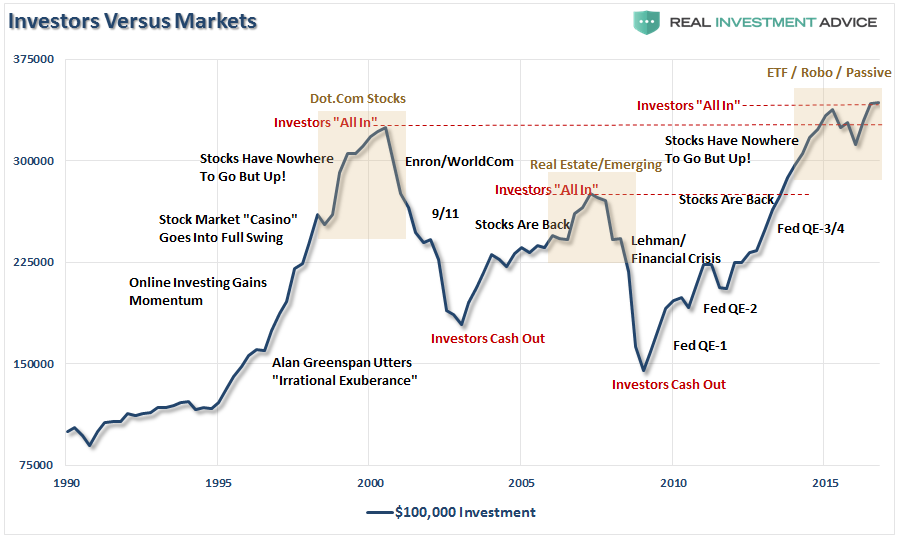

Human psychology and emotional behaviors are critically important to understand as they are the one constant in an ever changing financial landscape. I have shown the following chart before, which is not a new concept by any means.

Note the chart above is what has happened to a $100,000 investment in the S&P 500 Index. Notice the difference between the two charts above. While the S&P index has soared past previous highs, a $100,000 dollar investment has just recently gotten back to even. This demonstrates the important difference about the impact of losses on a dollar-based portfolio on investments versus a market-cap weighted phantom index.

The emotions of greed and fear continually dominate investor behavior. It is due to these emotional biases that instead of “buying low and selling high” the vast majority of individuals do the opposite. After the end of a correction process in the markets, individuals appetite for “risk” is extremely limited. The previous losses of personal wealth have left most anchored in despondency. As markets begin to recover individuals do not perceive the initial recovery as the return of an investible cycle, but rather an opportunity to “get out” of the financial markets and promising “never to return.”

It is not until very late in the bull-market cycle that individuals return to the “casino.” Of course, this is after a long period of being chastised by the mainstream media “for missing the rally” and admonishing advisors for not “beating the market.” After all, at this point who needs an advisor anyway? Everyone should just buy an index fund because “this time is different” and there is an overwhelming perception that there is “no risk” of chasing “risk.” [Think about that for a moment]

Does ETF Crowding, “Robo-Advisors” Mark A Top?

Near each major market peak throughout history, there has been some “new” innovation in the financial markets to take advantage of individual’s investment “greed.” In 1929, Charles Ponzi created the first “Ponzi” scheme. In the 1600s, it was “Tulip Bulbs.” Whenever, and where ever, there has ever been a peak in “investor insanity,” there has always been someone there to meet that need. In that past it was railroads, real estate, commodities, or emerging market debt; today it is “passive indexing.”

The latest innovations to come to market have been in two forms: “passive indexing” and it’s brethren “Robo-Advisors.” Robo-Advisors, a breed on online investment services, allows individuals to access “buy and hold” portfolio allocation models of low cost index funds with an automated rebalancing process. On the surface, it sounds like a winning idea with low cost portfolio management, index based performance, and immediate online access.

For the third time in the last 30 years, we once again hear the “Siren’s Song:”

Why would anyone pay an advisor and reduce their returns when all one has to do is buy an index and just hold on.

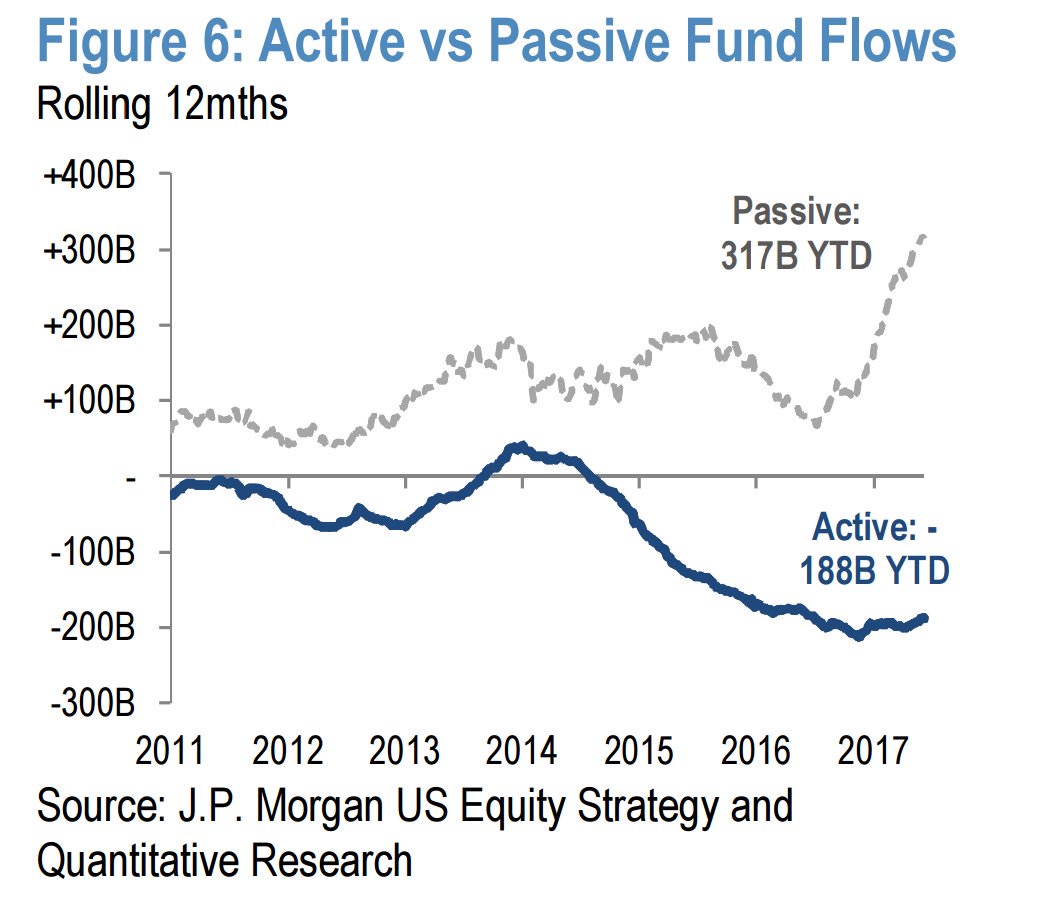

Not surprisingly, the repeated mantra of “passive indexing” by the mainstream media also finally filtered its way into the investing public who have decided they can wait no longer to “get back into the market.” This can be seen in the two charts below. The first is shift in assets from “actively managed” funds to “passive.”

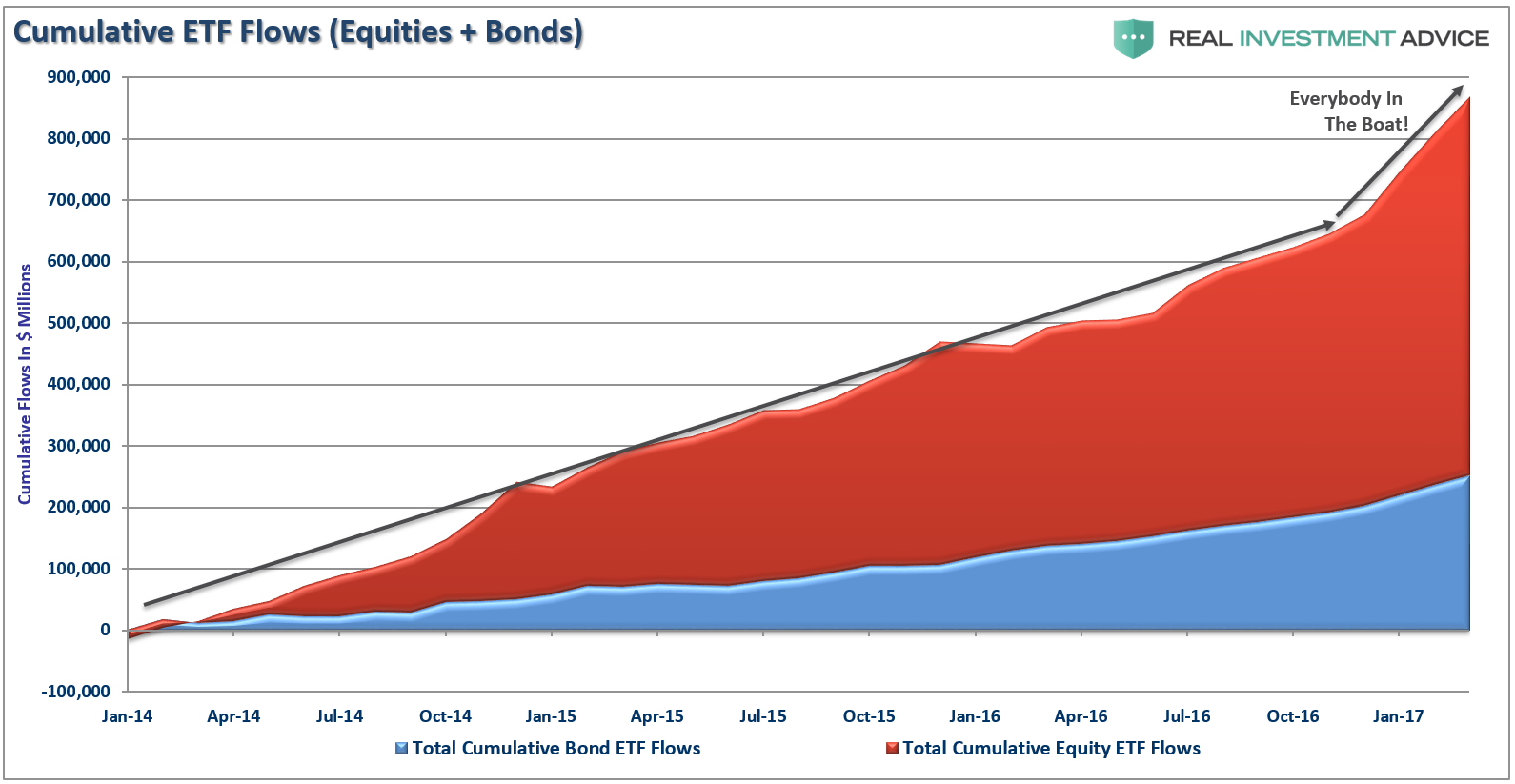

The second is the surge in equity-based ETFs in recent months.

Due to the liquidity driven surge in the markets over the last eight years, the increased optimism has once again created the belief that “monkeys throwing darts” can pick stocks as well as a veteran investment advisor. Therefore, why pay the fee for an advisor when buying a very low cost index fund will give you better performance? It is a valid question. History, however, has the answer.

The problem for Robo-Advisors and “passive indexing” has yet to come. As I have discussed previously, there is a duration mismatch between Robo-advisors and individual’s emotional behavior.

The investment time frame for Robo-Advisors is long-term based on historical returns of markets over time. In theory, the model is sound.

'If' an individual indeed invested in the model, ‘if’ they rebalanced regularly and ‘if’ they held for a 20-30 year period, depending on where in the market cycle they began, they would indeed perform very well.

There are a lot of “IF’s” in that statement.

Unfortunately, as discussed above, despite most individuals best intentions of being a long term investor, the reality is that their “long-term” time frame is only from today until the next major market correction begins. To put this into context, in the 1960s the average hold time for stocks was roughly six years. Today that hold time is from six weeks to six months. When the next downturn begins, as it eventually will, money will flee Robo-advisors in search of human contact, advice, and hope.

That is the cycle of innovation in the financial market place. Despite the best of intentions, and advances in innovation, humans will always seek out the comfort of other humans in times of distress. The rising notoriety of Robo-advisors and the crowding of investors into “passive indexing” are the current symbols of excess in the markets today. They will also be the “whipping boy” of the next decline as “passive indexing” is realized as a “foolish” investment strategy.

I have been around long enough to see many things come and go in the financial world, and there is only one truth: ” The more things change, the more they stay the same.”