Current interest rate levels are not a temporary phenomenon. We do not expect a rate hike for several years, and even beyond that, increases are likely to be very modest.

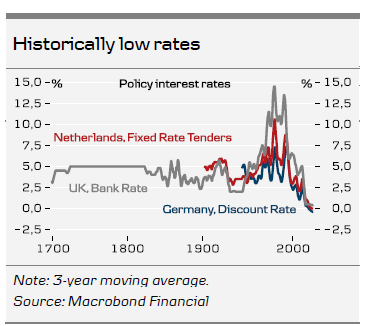

Since the financial crisis more than 10 years ago, we have had very low interest rates by historical standards. In the beginning, that was widely seen as the result of an extraordinary policy response by central banks caused by the extraordinary depth and length of the crisis. However, it is increasingly clear that the decline in interest rates is not so much a remedy against a short-term lack of demand in the economy as it is a structural shift in the global economy. The implication is that there is no reason to expect much higher interest rates in the coming years.

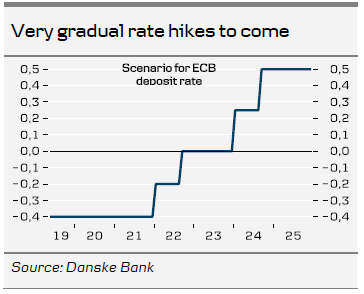

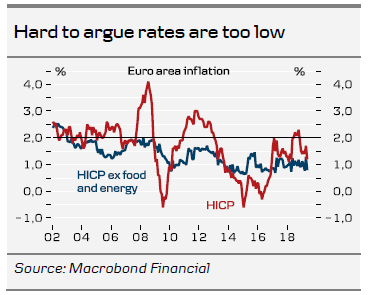

The economic recovery in the euro area has lasted for more than six years, and the economy is not far from its potential output and employment. Yet interest rates are still at record low levels, and nothing suggests that is about to change. Inflation, especially core inflation, is well below the ECB’s target, as are inflation expectations. We expect inflation pressure to increase, but only very slowly. Our interest rate forecasts cover the next 12 months, and we do not expect any rate hikes over that period, but it seems likely that it will be much longer than that before inflation has increased enough to warrant higher interest rates. The most likely scenario, in our opinion, is a rate hike in 2022 – of course, with great uncertainty.

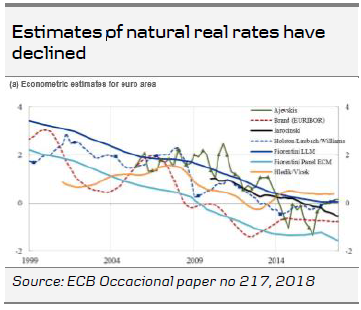

We are close to the natural rate

Actual short-term interest rates vary as central banks raise or cut them according to their assessment of the business cycle and inflation outlook. But they are usually seen to be set relative to a ‘natural’ or underlying level of interest rates. This natural rate is the one that would prevail in a neutral cyclical situation and it is basically determined by supply and demand for savings and investments. Larger savings will lower the natural interest rate, larger real investments in production capacity and housing will increase it. The natural interest rate cannot be observed directly, it must be estimated from looking at the behaviour of the economy in the past, and such estimates can vary considerably depending on the choice of methods and models. For the euro area, most estimates currently indicate a real natural interest rate of between -1 and 0 percent.

If inflation is, and is expected to be, close to 2% as the ECB targets, that implies a natural short-term nominal interest rate around 1.5%. However, inflation in the euro area has only been 1.3% on average over the past 10 years, and core inflation is currently even lower. Over the coming years, we expect inflation to increase very gradually, but not all the way up to 2%. At the same time, we expect the factors that have pushed down the natural interest rate to become even more pronounced, especially the demographic factors. Hence, our call for the ECB deposit rate is 0.5% five years from now - with a plus or minus depending on the cyclical situation at the time.

Low rates is a long-term trend

There is broad agreement that natural interest rates have been declining globally for the last 40 years or so, and especially rapidly since the financial crisis. Among the main reasons for this are:

Lower inflation. What matters is the real interest rate, and as inflation and inflation expectations have declined, so has the nominal interest rate.

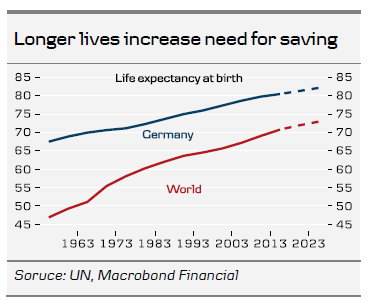

Increasing life expectancy. Over the last 40 years, the number of years a 65- year-old can be expected to live has increased globally (for example, by 3.3 years in Denmark – an increase of one month every year). This naturally leads to an increase in the desire to save for retirement among the working age population, as well as increased pressure from policy makers for greater personal savings in order to lessen the burden on public finances. In the very long run, the effect on the natural interest rate should be neutral, as the increased savings will at some point be turned into increased spending, but the effect is set to become even more negative over the coming 10 years at least.

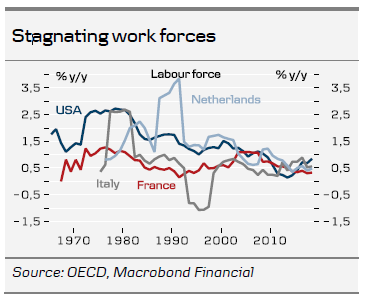

Slowly growing or declining working age population. Western countries have experienced large increases in their labour forces in the post-war period, from the baby boom generations and the wide-scale entry of women in the formal labour market. The generations now replacing retiring baby boomers are smaller, and activity rates are increasing less rapidly. Also, other countries, most notably China, are no longer seeing large demographically driven increases in their workforces. Lower workforce growth means lower demand for productive investments, all else being equal. However, some countries are seeing workforce growth from immigration and from people retiring later as life expectancy grows, and the potential for more inclusion in the labour market remains large in many countries.

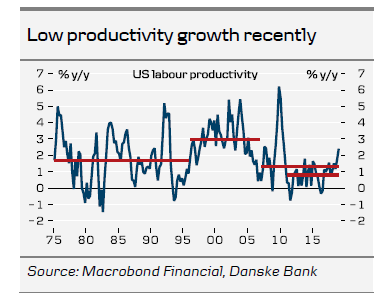

Lower productivity growth. There has been a steady decline in the productivity growth of labour in most OECD countries over the last 50 years. While it is more difficult to measure the productivity of capital, there appears little doubt that the growth rate of this has also declined significantly. The implication is that new investments are less profitable and hence it lowers the demand for capital for investment. This is the basis for the ‘rule of thumb’ sometimes mentioned that the long-term real interest rate is about equal to the rate of productivity growth. It is possible that technological breakthroughs or new productive uses of, for example, robotics could change that situation, at least temporarily, but we see it as most likely that productivity growth will stay muted compared to the post-war boom.

Higher mark-ups and risk premiums. While real interest rates on, for example, German government loans have declined sharply, there seems to have been little decline in the returns to business owners on real investments. This is surprising, as lower borrowing costs should make it worthwhile to take on some of the less attractive investment projects and thus drive down overall returns. One possible reason for this is weaker competition between companies, leading to higher markups and profits, all else being equal. That is consistent with the lower share of income going to workers in some (but by no means all) countries. A higher difference between the risk-free interest rate and investment returns can also be the consequence of a decline in risk willingness among investors. In any case, the consequence is that the risk-free rate is pushed lower than it otherwise would be to create sufficient investment to match savings.

Shock from the financial crisis. The decline in the natural interest rate has been especially pronounced following the financial and economic crisis of 2008-09. One possible explanation is that tightened financial regulation in the aftermath of the crisis has effectively increased the premium over risk-free interest rates on risky loans. Possibly, the mere shock of the crisis has also contributed to increasing risk aversion.

Higher inequality. A more unequal income distribution in many countries – for example, within Europe – may mean that a higher share of income goes to wealthy groups, who are more inclined to save than consume. That increases the total amount of saving for a given income level, and hence lowers the natural rate of interest.

Most of the factors mentioned above seem likely to continue to weigh on interest rates for the coming years, and the demographic situation is set to become more negative for interest rates over the coming 5-10 years at least.

Of course, trying to predict economic developments over such a long time horizon is extremely uncertain, and we might see different scenarios play out. One factor that might increase natural interest rates is an increase in productivity growth. Although the long-term trend in productivity growth has been declining for many years, technological changes can cause prolonged periods of higher growth, such as the one around 2000. For example, breakthroughs in robotics or self-driving cars might create the potential for large productive investments and hence demand for capital. Climate change, and policies to combat climate change, may also lead to a large need for investments.

Another factor that could push up interest rates is a shift towards more expansionary fiscal policy. In academic debates, the argument is gaining ground that governments should take advantage of low interest rates to increase their borrowing and increase investments that would raise the potential growth rate in the economy.

Long yields also kept in check

Long-dated yields are theoretically a mix of (1) expectations for future short-dated yields and (2) a term-premium for investing in long-dated bonds instead of investing in a series of short-dated bonds during the same period.

Short-dated nominal yields to stay low if neutral rate is low

If the market assumes that the neutral real rate will stay low or even negative for an extended period, it will tend to push long nominal yields lower as well, as expectations of short-dated nominal yields in the future will depend on real rate expectations. This is especially true if the market assumes that the real neutral rate will continue to drop.

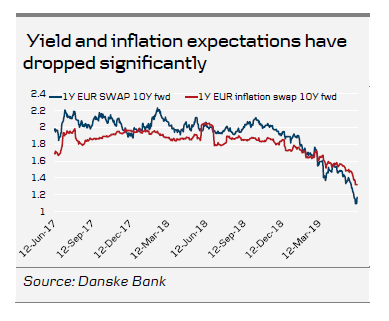

Today, the market assumes that the nominal 1Y EUR swap-rate will rise to roughly 1.15% in 10 years’ time, and at the same time inflation is expected to reach 1.3% in 10 years’ time. Hence, indirectly a real rate of -0.20% in 10 years’ time.

The market pricing indicates that even though we would consider today’s long yields to be low, it might in fact not be the case if neutral real rates stay at the current level or drop further. It does not mean that long yields cannot rise from the current level. We just argue that the trend is not necessarily upward sloping for long yields. We will still have, for example, cyclical fluctuations, but they will be around a lower average/trend.

The term-premium under pressure

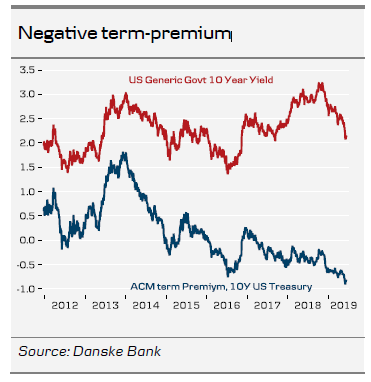

The term-premium is not observable in the market, but has to be estimated using different econometric techniques. The term-premium has historically been positive, but according to many models, it has turned negative in recent years. The chart to the right shows the termpremium for 10Y US treasuries.

It is to a large degree the same factors that affect the neutral real rate that affect the termpremium. The global savings surplus and the need to have duration in the portfolio has forced investors to buy bonds even as the term-premium is apparently low or negative. The global expansion of central bank balance sheets through various quantitative easing programmes has also been mentioned as an explanatory factor for depressing the global term-premium. The factors that depress the term-premium are not likely to disappear any time soon, which keeps long yields in check even if the cyclical outlook improves.

Long-dated yields kept in check by the same factors

All in, we argue that the factors that keep the neutral real rate low/negative also work to keep long-dated nominal yields low. Today’s yield level is not extraordinarily low. It does not mean that long-dated yields cannot rise, but the trend is not necessarily upward sloping. Hence, primarily changes in the cyclical outlook will decide the outlook for long-dated yields and, to a lesser degree, a ‘normalisation’ of policy rates.