The Caribbean island of Puerto Rico is in the throes of a debt crisis that recently reached a breaking point when it missed a $422 million bond payment due May 2nd. When asked in a subsequent interview about the likelihood of making future payments on the remaining $72 billion of debt, Puerto Rican Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla noted that the U.S. territory “does not anticipate having the money.”

Even a cursory review of Puerto Rico’s finances confirms Padilla’s claim of insolvency. The government is expecting deficits to grow from $14-$16 billion over the next five years, and for revenue to fall by $1.7 billion over that same five-year period. To makes matters worse the U.S. territory's unemployment rate is a lofty 12.2 percent.

The problem is simple: Puerto Rico’s debt burden is equal toover 100% of its GDP when including the $43 billion worth of unfunded pension liabilities. This situation is exacerbated by falling population growth and perpetually shrinking GDP.

This is an unsustainable burden for the Caribbean island that is home to 3.5 million residents. To put this in perspective, if Puerto Rico were a state it would be similar in size to Iowa, which carries a comparatively meager $15 billion in public debt and a debt to GDP ratio of just 11%. In fact, even big spending states such as New York only carry a debt to GDP burden that is just 25%.

Puerto Rican debt has been the darling of Hedge Funds and financial advisors for years because of thedesperatesearch for yield that has been exacerbated by the Fed’s ZIRP and by the government’s triple tax-free status of its bonds.

Sadly, this debt story has been told before. Politicians, lured bypower, convince citizens that economic prosperity comes from debt-fueled government spending. But when the promised growth never materializes tax payers are saddled with debt payments that far transcend the tax base.

The Island’s coveted tax-exempt status, coupled with no requirements for a balanced budget, allowed Puerto Rico to ignore the fetters of typical state spending and encouraged them to follow the fiscal policy of Greece.

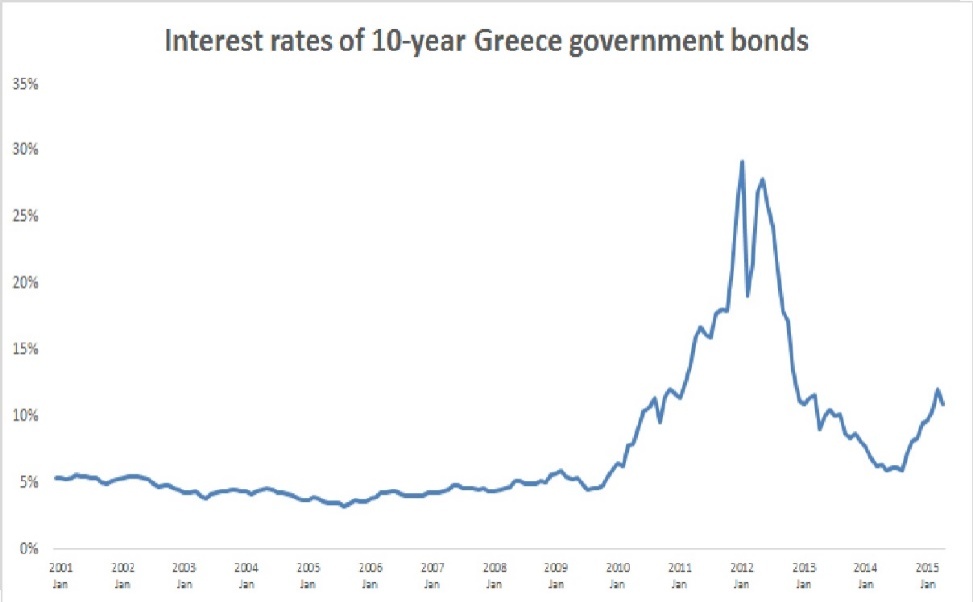

When Greece adopted the euro back in 2001 the prestige of a stronger currency enticed them into taking on debt beyond what their tax base could support.

In 2010 Greece began to experience its own crisis of confidence in the government’s ability to pay back its enormous debt load that had climbed to nearly 150% of GDP. This caused bond yields to become intractable; by 2012 the yield on the 10-Year Note ballooned to over 40%.

Then, assurances made by the ECB President, Mario Draghi, to do whatever it takes to bring down borrowing costs eventually brought rates back down to earth. And they have remained relatively quiescent ever since; despite Greece’s debt to GDP ratio hovering around 180% for the following three years after the bond market collapsed.

The fact is compared to Greece Puerto Rico is in better financial condition; it has a much lower debt to GDP ratio and has similar demographics and growth.So why does the Greek Ten Year Note yield just 7.5%? In comparison, $422 million of securities sold by Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank recently displayed a yield of 1,600%. So what is the reason for the trenchant difference in borrowing costs? The answer is simple: Puerto Rico cannot print their own currency and it does not have a central bank willing to monetize the debt.

This yield differential supports the theory that the current $8 trillion worth of negative yielding global sovereign bonds would be displaying yields significantly higher.In fact, if global investors were not convinced that central banks would always supply a bid for sovereign debt the bond yields of Japan, Europe and the U.S would be closer to those of Puerto Rico, or at least Greece circa 2012. This is because not only do these nations have a debt to GDP ratio that is higher than Puerto Rico, but also because they share similar faltering growth patterns.

The simple fact is a nation does not ever have to repay its debt; but must always convince bond holders that it has the ability to do so. And without a viable tax base all these nations have to lean on is the printing press. The sad truth is without continuous central bank intervention the yield curve for the entire sovereign debt complex would spin inexorably out of control. This is the real reason why central bankers are panicked about deflation and have inextricably inserted themselves into financial markets.